Last week, DePaul University’s new president, Rob Manuel, shared a message in honor of the Feast Day of St. Vincent de Paul. He detailed the concepts of radical hospitality and service as deeply connected to the spirit and life example of Vincent de Paul, an ongoing inspiration for us today. While the connection between mission and service is familiar to most at DePaul, in subsequent conversations I observed that the idea of radical hospitality was new to many. This was especially true in articulating the present day meaning of DePaul’s Vincentian mission. The concept of such hospitality, however, has deep roots in our Vincentian heritage and is rooted in the life example and testimony of Vincent de Paul. There is great spiritual depth to the practice and experience of radical hospitality, particularly when considering our mission.

Last week, DePaul University’s new president, Rob Manuel, shared a message in honor of the Feast Day of St. Vincent de Paul. He detailed the concepts of radical hospitality and service as deeply connected to the spirit and life example of Vincent de Paul, an ongoing inspiration for us today. While the connection between mission and service is familiar to most at DePaul, in subsequent conversations I observed that the idea of radical hospitality was new to many. This was especially true in articulating the present day meaning of DePaul’s Vincentian mission. The concept of such hospitality, however, has deep roots in our Vincentian heritage and is rooted in the life example and testimony of Vincent de Paul. There is great spiritual depth to the practice and experience of radical hospitality, particularly when considering our mission.

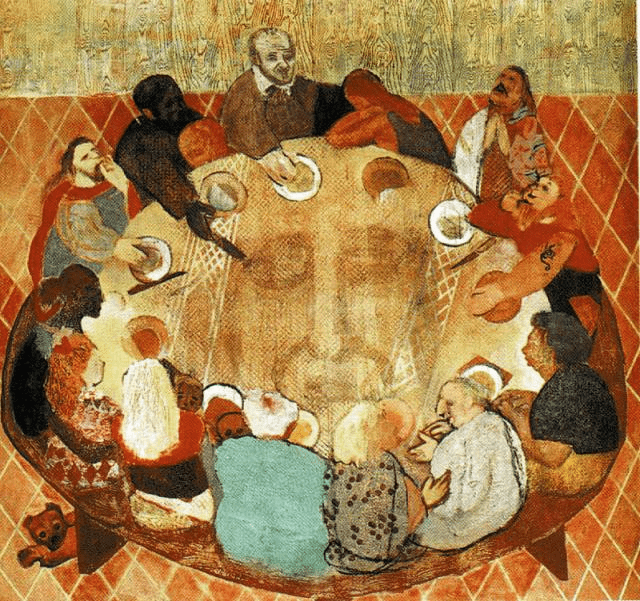

A common Vincentian story told at DePaul is often referred to as the story of the white tablecloth. In the foundational documents and rules established for the Confraternity in Châtillon-les-Dombes in 1617, Vincent de Paul explained the careful attention necessary when seeking to serve those in need. He recommended that missioners lay out a white cloth before serving food to a person in need, and that they engage in kind and cheerful conversation to better understand the context of that person’s story.(1) The attentive care communicated through gestures such as these reflect a recognition of the sacred dignity of those being served, as well as the essential relational dimension of human interaction, breaking down the distinction between “us” and “them.”

When Vincent established the Congregation of the Mission, he recognized the importance of establishing “a community gathered for the sake of the mission.” This community would not be based upon individual action, it would be built on the collective interdependence of those sharing a common purpose. Vincent took this further in establishing the Daughters of Charity alongside Louise de Marillac. Louise invited young peasant women into her personal space and formed a community. She recognized their potential and taught them to read and write, equipping them to be catalysts of change in their communities. Such hospitality was unprecedented at the time. Louise created entirely new opportunities that did not exist previously for women in society. With Vincent she shaped an intergenerational community, gathering women across all boundaries of social class. The Daughters believed that the “streets are our chapel,” and they continue to carry a spirit of personalism, openness, and hospitality outward, wherever they go.

In 2016, a special edition of the journal Vincentian Heritage was devoted to the theme of hospitality. It was inspired by our Vincentian spirit, so urgently needed in today’s world. The articles in this virtual compendium of Vincentian hospitality contain many insights on the transformative power of the practice of possibility.

The preface describes Vincent de Paul as a “hospitality practitioner” due to his desire to serve and care for others in the way that is best for them.(2) Subsequent articles further develop the theme through the lens of Vincentian tradition, emphasizing hospitality as a “sacred” experience that reflects the very nature of God. Vincent and Louise’s attention to the quality of the services they provided is singled out as a reflection of their deep, faith-based commitment to offering the best care possible to others, particularly those that society forgot or diminished.(3) An encounter of hospitality as a transformational event is highlighted “because we are engaging in new relations and opening ourselves to deep change.” In the process of encountering others, we must simultaneously address the harmful or unjust structures that get in the way of the effective care that hospitality demands.(4) Cultivating friendships and learning to listen deeply to oneself and the needs of others in the manner of Vincent de Paul is emphasized, as is the practice of hospitality to students of all faith traditions. We must recognize the importance of our words and actions in welcoming and caring for students, and in helping them to feel at home.(5) The intentional practice of hospitality, and how it effectively passes on the Vincentian mission and charism in the relational encounter between students and community partners, is also detailed.(6) Vincentian hospitality has been successfully used to address some of today’s most pressing societal issues.(7) Other articles discuss Vincent’s attentive care and concern for the sick and indigent, prisoners, and foreign migrants, and all those whom society tends to marginalize.(8) This edition truly illustrates how the practice of hospitality can serve as a catalyst for both inner and outer transformation.

Interestingly, an earlier Vincentian Heritage article by Sioban Albiol in DePaul’s College of Law points out that Vincent was himself a migrant and therefore he maintained a special concern for foreigners. This was reflected in the hospitality he provided to others.(9) The article states:

Saint Vincent de Paul must have felt the blessing and the pain of migration in his own life. Like so many economic refugees, at some personal cost to himself and his family. His father’s selling of two oxen to finance Saint Vincent’s studies is recounted by several authors. He left his home in order to pursue educational opportunity and economic security that could not be found in his place of birth. The land where he was born would have provided a bare existence.(10)

Vincent’s frequent reflection upon and practice of charity connects closely to the concept of hospitality. While today charity may sound soft and ineffective in the face of large, structured inequities, it also might be understood as the critical affective and relational dimension to justice. In fact, Vincent’s emphasis on charity was about action and generativity beyond the surface level.(11) Vincent advised his followers that charity involved the willingness to endure risks for the sake of offering hospitality to those in need: “If you grant asylum to so many refugees, your house may be sacked sooner by soldiers; I see that clearly. The question is, however, whether, because of this danger, you should refuse to practice such a beautiful virtue as charity.”(12) Enduring risks and vulnerability means extending ourselves beyond our comfort zone for the sake of others. Vincent’s charity, and his personal transformation over time, began by responding to the needs of those in front of him. He saw it as a virtue and an imperative of his Christian faith to be approachable.(13)

The resources above may help to shape a distinctive Vincentian hospitality vitally integral to sustaining and energizing the daily practice of our mission as we engage students, colleagues, community partners, and guests and visitors within our DePaul campus and community. However, in the spirit of Vincent de Paul, we will only learn radical hospitality and understand its profound meaning through concrete actions and experiences.

How might a radical Vincentian hospitality become concrete and real in our day-to-day interactions and encounters?

How might the practice of hospitality lead to both inner and outer transformation—within us and within the communities of which we are a part?

Reflection by: Mark Laboe, Associate VP, Mission and Ministry

1) See Document 126, Charity of Women, (Châtillon-Les-Dombes), 1617, CCD, 13b:13; and Document 130, Charity of Women, (Montmirail – II), CCD, 13b:40. At: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentian_ebooks/38/.

2) Thomas A. Maier, Ph.D. “Preface: The Nature and Necessity of Hospitality,” Vincentian Heritage 33:1 (2016), available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol33/iss1/1.

3) Thomas A. Maier, Ph.D., and Marco Tavanti, Ph.D., “Introduction: Sacred Hospitality Leadership: Values Centered Perspectives and Practices,” Ibid., at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol33/iss1/2.

4) Ibid, p. 5.

5) Annelle Fitzpatrick, C.S.J., Ph.D., “Hospitality on a Vincentian Campus: Welcoming the Stranger Outside our Tent,” Ibid., at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol33/iss1/9.

6) Joyana Dvorak, “Cultivating Interior Hospitality: Passing the Vincentian Legacy through Immersion,” Ibid., at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol33/iss1/16.

7) J. Patrick Murphy, C.M., Ph.D., “Hospitality in the Manner of St. Vincent de Paul,” Ibid., at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol33/iss1/12.

8) See John E. Rybolt, C.M., Ph.D., “Vincent de Paul and Hospitality,” Ibid., at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol33/iss1/5; John M. Conry, “Reflections from the Road: Vincentian Hospitality Principles in Healthcare Education for the Indigent,” Ibid., at: http://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol33/iss1/14.

9) Siobhan Albiol, J.D., “Meeting Saint Vincent’s Challenge in Providing Assistance to the Foreign-Born Poor: Applying the Lessons to the Asylum and Immigration Law Clinic,” Vincentian Heritage 28:2 (2010), at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol28/iss2/20/.

10) Ibid., p. 282.

11) Conference 207, Charity (Common Rules, Chap. II, Art. 12), 30 May 1659, CCD, 12:223, at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentian_ebooks/36/.

12) Letter 1678, Vincent de Paul to Louis Champion, Superior, In Montmirail, November 1653, CCD, 5:49, at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentian_ebooks/30/.

13) See Robert Maloney, C.M., “The Way of Vincent de Paul: Five Characteristic Virtues,” Via Sapientiae, (DePaul University, 1991), at: Five Characteristic Virtues; also Edward R. Udovic, C.M., Ph.D., “‘Our good will and honest efforts.’ Vincentian Perspectives on Poverty Reduction Efforts,” Vincentian Heritage 28:2, at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol28/iss2/5.