Nothing causes me to examine myself, and my relationship with God, more closely than the Christian season of Lent, when the earthly and divine aspects of our human existence come together in their fullest, most challenging expressions. In my imagination, I see myself standing alone on a mountaintop for the 40 days of Lent, with one hand holding a mirror to my face, reflecting my authentic humanity with all of its fear and vulnerability. The other hand is stretched out, grasping for something that I cannot see, but that I hope is there. It is something that will help strengthen me, sustain me, and keep me safe. The divine presence in the midst of the human struggle.

Lent has taken on an even more personal and intimate significance for me over the last few years. For it was on Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent, in 2018 that my father died. He went peacefully, surrounded by his family, with remnants of the ashes symbolizing his faith and his humanity still faintly visible on his forehead. It was a poignant embodiment of the traditional Ash Wednesday blessing “remember, from dust you came and unto dust you shall return.”

Recently, I came across a story from Vincent de Paul about his own father that, although centuries old, mirrors my own experience and serves to illustrate our ongoing need for what Vincent called simplicity. Today we might call it authenticity or integrity.

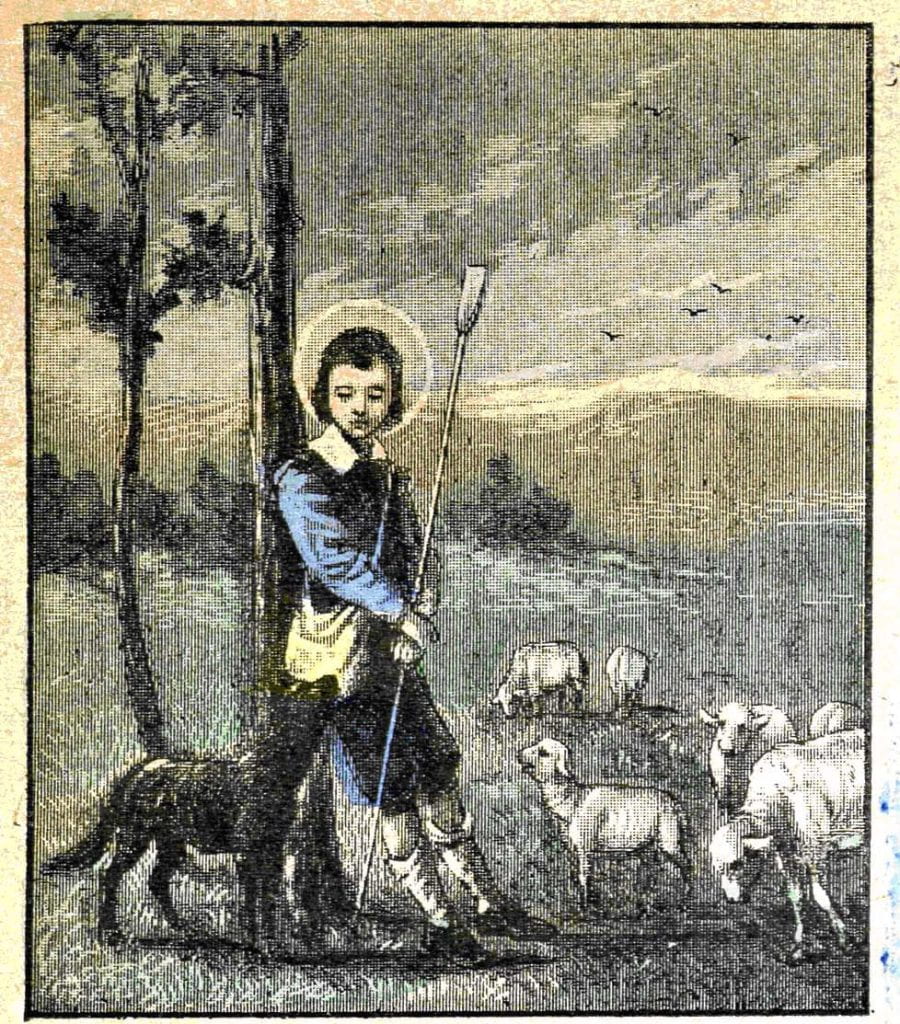

The story goes that once, when Vincent de Paul was a young seminarian, his father came to visit him. Vincent was self-conscious about his humble background and had not shared with his classmates that his family were poor farmers. When the porter announced that a plainly dressed man was asking for him, Vincent looked out the window and saw that it was his father, wearing shabby work clothes, standing outside waiting at the door. Vincent was so embarrassed at the sight of his father that he pretended he did not know him; he said there must be a mistake and told the porter to send the man away.[1]

I feel a guilty connection with Vincent around our fathers as once, when I was a young attorney working at a large law firm, my father came to visit me at my office. As was the case with Vincent’s father, my dad had been a farmer. Years of working in the sun had taken their toll and, on this particular day, my dad was wearing a big bandage on the side of his nose where he had just had a benign skin cancer removed. Just as my dad and I entered the elevator to head up to my office, one of the partners from the law firm got on with us. The older attorney smiled and nodded hello to us and my dad followed suit. But I, embarrassed by my dad’s appearance and insecure around my superior, could only mumble something like “you’ll have to forgive my dad … he’s just been to the doctor.” The rest of the elevator ride was painfully awkward. Years later, I still cringe at that memory.

Vincent told the story of his own embarrassing behavior towards his father multiple times in his later life. In part, I suspect he did so to pay belated homage to the simple, loving man who had gone out of his way just to see his son at seminary. But Vincent also used the story for instruction. He was teaching his community an important lesson, one that is as relevant today as it was then: challenging as it may be, we must be willing to know and accept our lives and ourselves. This means not just the good and pleasing parts, but also the tough and embarrassing parts, and the times we may have made mistakes or even failed at something important. Without this self-awareness and acceptance, we will find it next to impossible to accept those around us. We will also not be able to bring the integrity, honesty, authenticity, and in Vincent’s words, the simplicity that is necessary to win hearts, build relationships, and impact lives.

This quality of integrity or authenticity that Vincent prized so greatly was clearly not on display the day his father paid him a visit at the seminary (nor, for that matter, when my dad visited me). But it is gratifying to remember that with time and practice it can develop as it so clearly did for Vincent. With intentional effort to accept our entire selves, flaws and all, we will find it easier to offer our lives to the service of others.

Reflection Questions:

- Are there aspects of yourself, and your life, that you find difficult to accept? Why do you think this, and is there anything you can do to change it?

- Here at DePaul, do you find that you are usually able to be your authentic self? Are there ways that you might be able to contribute to helping make our community a place where all members can be their full and authentic selves?

Reflection by: Tom Judge, Assistant Director and Chaplain, Faculty and Staff Engagement, Division of Mission and Ministry

[1] Quoted in Pierre Coste, The Life and Works of Saint Vincent de Paul, trans. Joseph Leonard, C.M. (New York: New City Press, 1987), 1:14. Available online at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/coste_engbio/3/.