I recently had the good fortune of accompanying leaders from DePaul, St. John’s, and Niagara, the three American Vincentian universities, to France for a Vincentian Heritage tour. The trip was a culmination of their COVID-extended participation in the Vincentian Mission Institute program, and it was the first Heritage tour involving DePaul faculty and staff since 2019.

I recently had the good fortune of accompanying leaders from DePaul, St. John’s, and Niagara, the three American Vincentian universities, to France for a Vincentian Heritage tour. The trip was a culmination of their COVID-extended participation in the Vincentian Mission Institute program, and it was the first Heritage tour involving DePaul faculty and staff since 2019.

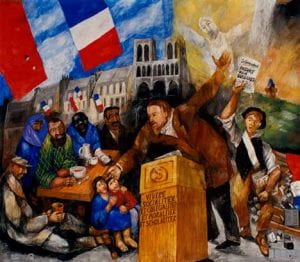

The trip gave me an opportunity to reflect more intentionally and vividly on Vincent de Paul, Louise de Marillac, Frédéric Ozanam, and others in the Vincentian Family over the past 400+ years and their relationship to our current work at DePaul University. There were many striking insights for me during the experience, often connected to a deepened appreciation for the enduring legacy of Vincent de Paul, the “Lazarists” (Vincentians), and the Daughters of Charity throughout much of France. Certainly, the many churches we visited in Paris and beyond display numerous images, statues, paintings, and plaques that commemorate Vincent and his impact. Yet Vincent’s visible and sustained presence clearly goes beyond church walls. His life and work as a priest had a broader effect on French society, and he even gained the respect of the antireligious revolutionaries of the eighteenth century. He was a public religious figure whose service rippled outward to the peripheries of society where the poor and otherwise forgotten dwelled.

The trip to Vincent’s birthplace in Dax and to the site of his university education in Toulouse invited reflection on his young adult development and early priesthood. We saw the important site of Folleville, on the former lands of the de Gondi family, where Vincent had a transformative experience, where we frequently imagine Madame de Gondi posing the memorable “Vincentian question.” We remembered the foundation of the enduring model of the Confraternities of Charity when visiting Châtillon-sur-Chalaronne. And we walked through the streets of Paris to places that touched on the memory of Frédéric Ozanam and the founding of the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul. Moreover, it seemed everywhere we went, we found the continued presence and the historical echoes of the Daughters of Charity, including Louise, Catherine Labouré, and Rosalie Rendu.

So, why does all this history still matter so much to us now? Why would we spend extended time in present-day France walking in the footsteps of the founders of the Vincentian tradition?

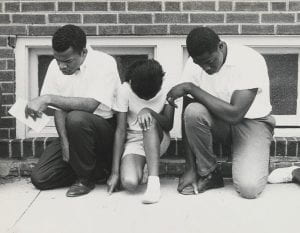

What ultimately matters in this exploration of our history is that we become inspired to carry on the Vincentian legacy in concrete ways through our lives and work today because, quite simply, our world still desperately needs it. Our Vincentian mission is as compelling now as it was 400 years ago: to sustain and enliven a community of people dedicated to service, charity, justice, and a purpose beyond themselves.

For generations now, Vincent, Louise, Frédéric, and others in the Vincentian Family have asked what it would mean for us to orient our time, our efforts, our intentions, and our vision more radically around the values reflected in the Jesus of the Gospels. Their enduring legacy reflects their response to this question.

Regardless of our religious convictions or the nature of our work, the legacy of Vincent, Louise, and the Vincentian Family invites each of us to ask:

- How might we orient our lives so that our life and work manifest the generosity, service, and care for others reflected in the living spirit of our Vincentian predecessors?

- What can we put in place that will outlast us, that will endure for the betterment of the common good?

- How can we build and inspire the community of people that is DePaul University to be focused on this mission together, and in so doing, to address the larger societal needs of today?

Like those of our predecessors, may our responses to these questions be proclaimed through our actions.

Reflection by: Mark Laboe, Assoc. VP for Mission and Ministry