Reflection by: Mark Laboe, Interim VP for Mission and Ministry

Some version of this question has often been posed to me and my colleagues in Mission and Ministry over the past several weeks, as the university community braces for the impact of budget and staffing cuts. Unfortunately, there is no magic pill or solution that will serve to help every person or situation. These are hard moments for all. Many are feeling bad and maybe hurting. We may feel let down, angry, and without much hope in sight. We may wish things were otherwise. This is the reality before us. Yet, we can and will move through it together when we do so with care for ourselves and others.

Some version of this question has often been posed to me and my colleagues in Mission and Ministry over the past several weeks, as the university community braces for the impact of budget and staffing cuts. Unfortunately, there is no magic pill or solution that will serve to help every person or situation. These are hard moments for all. Many are feeling bad and maybe hurting. We may feel let down, angry, and without much hope in sight. We may wish things were otherwise. This is the reality before us. Yet, we can and will move through it together when we do so with care for ourselves and others.

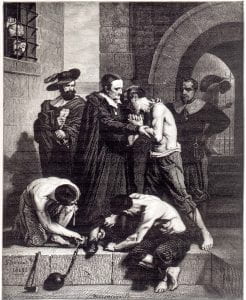

In seeking some sense of support and orientation from our Vincentian heritage, a few pieces of wisdom may provide some sustenance or insight to aid us through the current realities with continued resilience and hope. Also, in thinking about this question, it becomes clear that what is suggested here are mostly practices that are, ideally, always some part of our way of life. They just become even more important in times of challenge, stress, and difficulty.

1. Remember Who You Are

Vincent de Paul encouraged his followers: “Please be steadfast in walking in the vocation to which you are called.” (CCD 5:256) A good starting point is to remember, especially in moments of difficulty, that you are (still) a person who has much to offer to the world and those around you. You have a life of experience, learning, and successes. You have overcome challenges before. The external circumstances of your life do not change that fact. You also have a vocation (a purpose) to live out in whatever setting or situation you find yourself, and you are far more than just your work life. You have core values that are important to you and that you want to embody in your life. You are not just a machine producing widgets, but a human being who hopes and dreams, who loves, who has much to offer to those around you.

Though we may feel shaken, it is important that we do not allow difficult moments to lead us to forget or stray from our fundamental vocation and identity. Rather, we must use the occasion to reach even deeper into what is at the core of who we are and to find our roots there. This moment may simply be an invitation to grow stronger in understanding and conviction about what exactly that core identity and vocation is for us.

You may find that taking a moment to look at the “long view” of your life may help—using the well-known adage to “begin with the end in mind.” That is, envision who you want to have become as a person at the end of your life, then consider how you can continue to be true to that and to move in that direction even through this difficult moment.

2. Never Go It Alone

One of Vincent de Paul’s key insights came in the recognition that the mission to which he was called, or that he was entrusted with, was much bigger than he could fulfill on his own. He needed others, if his mission would ever be realized. We are all like Vincent in this way, even if we may lose sight of it when things are going smoothly. In a society that urges one to be an independent achiever, the fact remains that we are interdependent creatures. We each have a life to lead and a mission to fulfill as individuals, AND we can’t do it alone. At times like these it’s good to reflect on the fact that who we have become is a result not just of our own efforts and accomplishments but of the help and support of many other people around us. This is the human way, and it is the Vincentian way. So, especially in times of difficulty, don’t forget that, or pretend it can be otherwise.

Ask yourself who your people are, who you can lean on, who you can develop a stronger relationship with, and how you can put yourself in spaces to be surrounded by a community of support. This may require vulnerability. It may require a recognition of our limits. It will require an acceptance of our interdependence with others in our life and work. Who are your companions on the journey of life? Who are the people who understand you and what you are all about? Who can you lean on? Who helps you remember who you are and what you are all about? Who do you learn from or draw strength and comfort from? Who can you have fun and laugh with? Surround yourself with the people who bring you life along with the support and companionship you need right now—and all the time!

Additionally, one of the best ways to remain grounded and resilient in challenging times is to try and look for ways you can be supportive of and care for others. This is a very important piece of wisdom, and very Vincentian. Often when we are faced with difficulty, looking for ways that we can be of service to others will end up being exactly what WE need, more so than focusing only on ourselves. Interdependence means others are also counting on us to be a support to them. It’s both-and and not either-or.

3. Take One Step at a Time

Vincent de Paul advised his followers that “Wisdom consists in following Providence step by step.” (CCD 2:521) He reiterated that we should not seek to step on the heels or run ahead of Providence. My wife and I have our own similar phrase we share with one another and with our children during tough times: “just do the next thing.”

A common piece of Vincentian spiritual insight is that we need to look for and find God in the reality before us, the person before us, and with each present moment. In that moment or encounter, right in the midst of that reality, lies the opportunity to put charity and love into practice, or to practice who we seek to be and become.

As much as we’d like to sometimes, we can’t fast forward through our lives. Doing so wouldn’t be very helpful, either. Much anxiety is derived from stories created in our own mind about some imagined future outcome that has not yet happened. Such stories are often fear-based, or self-protective, and not often accurate.

So, can we “trust the process” and the unfolding journey of life? Vincent de Paul’s understanding of Providence portrayed a trust and belief that what was needed to live our vocation, to fulfill the purpose entrusted to us, has been given or will be given. It is incumbent on us to trust in this and to open our eyes to the gifts made available to us in the current moment and with each step along the way. One step at a time. Just do the next thing.

4. Trust that Love is Inventive to Infinity

“Love is inventive to infinity,” said Vincent de Paul! (CCD 11:131) His words offer an invitation to see and act creatively and to approach every moment and situation with an openness to what is possible. We can always do something coming from a heart of love. Do the next thing, or in this case, take the time to imagine and act on the next thing. Create the next thing. Actively explore what is possible. The current moment is not the end of the road, but the beginning of the next step of the journey.

There is a common piece of practical wisdom accredited to various public figures that says, “it is easier to walk our way into a new way of thinking” than to “think our way into a new way of walking.” The practice of design thinking suggests that we need to experiment and explore new ideas through our actions and not just in our heads.

When safe spaces are created to brainstorm together with others, new ideas can often surface. Many find the practice of creative arts like drawing or doodling, painting, journaling, dancing, or perhaps walking meditation can “loosen up” our thinking and help us to see in new ways. I find long runs are helpful breeding ground for new insight. Imagine various possibilities. Be open to the invitation to find ways to “love to infinity.”

5. Practice Gratitude

“You should not open your mouth except to express gratitude for benefits you have received…”, said Vincent de Paul. (CCD 5:51) Gratitude is the ultimate antidote against falling into despair or helplessness or escaping a mind that is caught in a spiral of anxiety, stress, or hurt. Yet, somewhat counterintuitively, sometimes the practice of gratitude, or truly allowing ourselves to feel gratitude, requires intentionality. It may take some regular practice or inner work on our part, especially when we are feeling anxiety, stress, or hurt. If we are feeling shut down or closed, we may need to consciously engage our will and our desire to work at locating gratitude in our minds and heart. For a little while, we may need to “fake it until you make it,” as the common 12-step wisdom suggests. Or, we might need to “act as if” we can, as a therapist may tell us, even if we are not feeling up to it in the moment.

In whatever way we manage to get there, allowing ourselves moments to sit with and feel gratitude for small or big things in our life, that we appreciate or recognize as good or beautiful, can be healing, grounding, nourishing, and re-orienting. It is a practice worthy of our time and energy, individually and collectively, especially as we move through difficult experiences.

Reflection Questions:

- When you ask what is most essential to who you are as a person, what comes to mind and how can you ground yourself more deeply in these values, commitments, or characteristics?

- What does accepting our interdependence mean to you in this moment and how can you recognize and live that out?

- What is one step that you can take forward right now… with love for yourself and others? With creativity and hope?

- List and spend a little time pondering on those things that you are grateful for in this moment.