A number of years ago, the political and cultural commentator David Brooks penned a thought-provoking article juxtaposing resume virtues with eulogy virtues.[1] While resume virtues are skills that you bring to the marketplace, eulogy virtues run deeper and define one’s depth of character. Eulogy virtues are the characteristics that we recall at a person’s funeral when we seek to describe the quality of their life.

A number of years ago, the political and cultural commentator David Brooks penned a thought-provoking article juxtaposing resume virtues with eulogy virtues.[1] While resume virtues are skills that you bring to the marketplace, eulogy virtues run deeper and define one’s depth of character. Eulogy virtues are the characteristics that we recall at a person’s funeral when we seek to describe the quality of their life.

According to Brooks, although most of us would probably agree that eulogy virtues are the most important, our culture and educational systems tend to put more effort into teaching skills for professional success. As a result, many of us neglect to cultivate the skills necessary to deepen our interior lives. We don’t until life confronts us with situations that require us to wrestle more profoundly with questions of meaning and purpose.

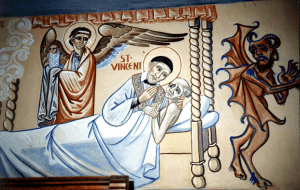

Saint Vincent de Paul’s trajectory seems to mirror the developmental shifts that Brooks lays out. Indeed, much of Vincent’s early experience reveals the ambitions of a young cleric who, motivated by “chances for advancement” and thoughts of “an honorable retirement,”[2] focused on furthering his ecclesial career and “building his resume.” While spiritual and ecclesial formation were certainly an integral part of his theological training, Vincent’s initial priestly motivation stemmed primarily from his desire to escape the financially uncertain life of a peasant farmer. As a result, Vincent, “the eager and ambitious cleric,” sought upward mobility by climbing the ecclesial ladder.[3]

Yet Vincent’s dreams of social advancement did not remain the driving force of his ministry for long. Amid the twists and turns of his vocation, a series of pivotal moments would challenge Vincent’s aspirations and invite him to think beyond himself and consider those in front of him who were living in deprivation. Prompted by such encounters as his visit to a dying peasant in 1617,[4] Vincent began to focus his ministry primarily on the needs and spiritual well-being of those who were poor and abandoned, whose dignity was not often recognized in seventeenth-century French society. He became immensely dissatisfied with the way the world appeared around him.[5] Yet, rather than accept the status quo, he channeled his frustration into a quest to build the world that he wanted to see.[6]

In tangible terms, these spiritual invitations led Vincent to abandon his desire for his own career advancement in favor of seeking a more just and equitable world. Consequently, he spent the rest of his life not merely asking, What must be done?[7] but using his actions as a pathway to live his way to the answer.

As Brooks notes, “some people have experiences that turn their careers into a calling.” While Vincent’s motivation to do good stemmed from his desire to build the Kingdom of God, his trajectory as an ambitious young clergyman might never have changed direction were it not for his ability to listen deeply and respond to what God asked of him. Vincent quite simply longed to serve God faithfully. The cries of those on the margins transformed his heart and motivated him to use “the strength of [his] arms and the sweat of [his brow]”[8]

Reflection Questions:

“We all go into professions for many reasons: money, status, security. But some people have experiences that turn a career into a calling.”[9]

Have there been moments in your career at DePaul when you have experienced your work as a calling? What was it about these moments that transformed your work?

What do you feel called to build in your life right now?

Reflection by:

Siobhan O’Donoghue, Director of Faculty and Staff Engagement, Division of Mission and Ministry

[1] David Brooks, “The Moral Bucket List,” New York Times, April 12, 2015, Sunday Opinion, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/12/opinion/sunday/david-brooks-the-moral-bucket-list.html.

[2] Letter 0003, “Vincent de Paul To His Mother, in Pouy,” 17 February 1610, CCD, 1:15 Available on line at: https://digicol.lib.depaul.edu/digital/collection/depaul01/id/84/rec/1

[3] Douglas Slawson, C.M., “Vincent de Paul’s Discernment of His Own Vocation And That of the Congregation of the Mission,” Vincentian Heritage Journal 10:1 (1989): 6. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol10/iss1/1.

[4] Luigi Mezzadri, C.M., and José María Román, C.M., The Vincentians: A General History of the Congregation of the Mission, trans. Robert Cummings (New York: New City Press, 2009), 1:10. Quoted in Scott Kelley, “Vincentian Pragmatism: Toward a Method for Systemic Change,” Vincentian Heritage Journal (2012): 31:2. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol31/iss2/2.

[5] Edward Udovic, C.M., Ph.D. “St. Vincent de Paul, A Person of the 17th Century, a Person for the 21st Century,” Office of Mission and Ministry DePaul University, YouTube video, January 16, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zrwez_neJT4.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Edward R. Udovic, C.M., Ph.D., “’Our good will and honest efforts.’ Vincentian Perspectives on Poverty Reduction Efforts,” Vincentian Heritage Journal (2008): 28:2, 72. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol28/iss2/5.

[8] Conference 25, “Love of God,” n.d., CCD, 11:32. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentian_ebooks/37/.

[9] Brooks, “Moral Bucket List.”