“Two roads diverged in a wood, and I – I took the one less traveled by.”[1]

DePaul University’s humble origin story began in 1898 when the Vincentians established Saint Vincent’s College to educate “the sons of Chicago’s burgeoning Catholic immigrant population.”[2] Since these early days, DePaul’s understanding of who we are called to be has continued to be formed and informed by pragmatic wisdom and visionary thinking. Indeed, the same innovative seeds that led to the establishment of “the little school under the el” continue to bear fruit today. By participating in processes such as Designing DePaul, we are once again being invited to help shape DePaul’s future.

Innovative thinking is certainly imprinted in our Vincentian DNA. One has only to consider the ministries of Vincent and Louise to see how they used their pioneering and imaginative spirits to develop creative solutions to the complex societal challenges of their day.

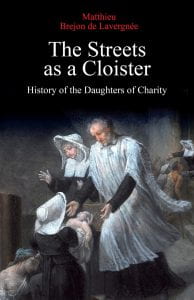

A particularly compelling example of this dynamic can be seen in the insightful way in which Vincent and Louise co-founded the community of religious women known as the Daughters of Charity. It is important to note that “in 1633, when Vincent de Paul and Louise de Marillac assembled the first Daughters of Charity, no community of women existed in France which worked outside the walls of the cloister.”[3] Such a restriction presented a challenge to the establishment of this community, since “Vincent de Paul wanted a company endowed with great mobility, in a position ‘to go everywhere,’ in direct service of the neighbor.”[4] Thus, the Daughters needed to have the freedom to serve on-site, in such ministries as visiting the sick in their homes or in hospitals, caring for wounded soldiers on the battlefield, or tending to the galley prisoners. Consequently, confining the Daughters’ movements to the cloister was incompatible with their purpose.

Confronted with this incongruity, Vincent and Louise chose to break with the norms of the other communities they saw around them and create a different kind of experience: a community of consecrated women who would live and serve “in the world.” In fact, the streets would become their cloister.

As Vincent was keenly aware of the distinctive nature of the Daughters, he would make a point of emphasizing their difference from other religious communities. Hence, he would use the term house instead of monastery or convent, and confraternity or society instead of congregation. Furthermore, one of the defining characteristics of the Daughters of Charity was that they remained secular, yet they pronounced annual private vows.[5] This practice continues to this day.

The new orientation of this community would eventually inspire the growth of many congregations of women in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These too would commit themselves to the care and service of their neighbors and achieve official ecclesiastical approval.[6]

At DePaul today, the same spirit of innovation that gave birth to the Daughters of Charity can serve as a beacon as we consider how best to Design DePaul and as we continue to identify new ways to respond to current challenges.

Reflection questions:

What seeds of hope might you take from Vincent and Louise’s approach as they navigated seemingly insurmountable hurdles?

How, in your work, might you find evidence that “love is inventive to infinity?”[7]

Reflection by: Siobhan O’Donoghue, M. Div., Director of Faculty and Staff Engagement

[1] Robert Frost et al., The Road Not Taken: A Selection of Robert Frost’s Poems (New York: H. Holt, 1991).

[2] Dennis P. McCann, “The Foundling University: Reflections on the Early History of DePaul,” in DePaul University Centennial Essays and Images, ed. John L. Rury and Charles S. Suchar (Chicago: DePaul University, 1998), 52. Available online at https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentian_ebooks/20/.

[3] Massimo Marocchi, “Religious Women in the World in Italy and France During the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries,” Vincentian Heritage 9:2 (1988). Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol9/iss2/1205.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 206.

[6] Ibid., 209.

[7] Conference 102, “Exhortation to a dying brother,” 1645, CCD, 11:131.