For almost two years now, I have been photographing the discarded masks I’ve encountered on my walks around the city. By the end of the autumn quarter 2021, I had accumulated close to 500 mask photos, and this practice has continued. When I traveled to Australia in June 2022, I found masks on the ground there, too. I traveled to Ontario, Canada in August and, again, found the ubiquitous masks. A September weekend in the borough of Queens, New York yielded more masks for my growing digital collection. And in November, on a trip to Paris, I found even more. Such is the nature of collections: they start small and, over time, the numbers grow. One must be patient. Our culture, however, doesn’t tend to traffic in patience. We want it now.

For almost two years now, I have been photographing the discarded masks I’ve encountered on my walks around the city. By the end of the autumn quarter 2021, I had accumulated close to 500 mask photos, and this practice has continued. When I traveled to Australia in June 2022, I found masks on the ground there, too. I traveled to Ontario, Canada in August and, again, found the ubiquitous masks. A September weekend in the borough of Queens, New York yielded more masks for my growing digital collection. And in November, on a trip to Paris, I found even more. Such is the nature of collections: they start small and, over time, the numbers grow. One must be patient. Our culture, however, doesn’t tend to traffic in patience. We want it now.

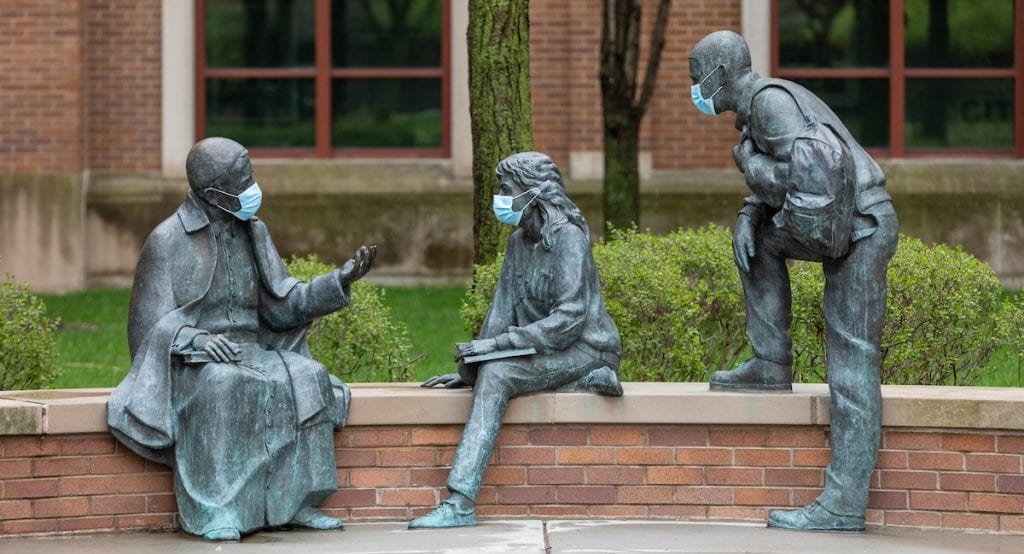

In a letter to Sister Anne Hardement, Saint Louise de Marillac wrote, “Do not be upset if things are not as you would want them to be for a long time to come. Do the little you can very peacefully and calmly as to allow room for the guidance of God in your lives. Do not worry about the rest.”[i] As a health communication scholar, I recognize at once Louise de Marillac’s advice as it relates to the twin aspects of coping: problem-solving (or changing what can be changed) and emotional adjustment (adapting to what cannot be changed).[ii] While it is not always easy to simply “not worry,” there is some peace to be found in accepting a predicament and doing what can be done to move forward. I didn’t know what I was going to do with all these mask photos until I happened to mention the “project” to Robin Hoecker, my colleague in the College of Communication, who happens to be a photojournalist. And our interactive collaborative photo mosaic project of the image of Vincent de Paul—“Unmasked”— was born.[iii]

When I’ve shared the “Unmasked” project with others, a common response has to do with this strange paradox of making art out of what is ostensibly environmentally injurious litter. For me, the masks on the ground are polysemic; there are many ways to read this symbolic detritus of the pandemic. In addition to indicating an irresponsible act of pollution, the masks on the ground—particularly those I photographed almost two years ago—seem emblematic of our community desire to move on too quickly.

This worldwide phenomenon of the Covid masks on the ground, I believe, symbolizes the liminal stage of the Covid pandemic. “Liminal” comes from the Latin “limen” or threshold. Anthropologist Victor Turner refers to the liminal as “betwixt and between,” the transitional or intermediate stage in a rite of passage.[iv] The liminal is loaded with challenges and ambiguities and is often precarious. For comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell, the liminal stage is part of the initiation stage, what he termed “the belly of the whale.”[v]

Few would deny Covid has been a collective rite of passage. Many of us recognize those betwixt and between times in our lives. This is true especially for our students. For example, there is the liminal moment of crossing the stage to receive a degree and a handshake with the university president. This march across the Wintrust Arena stage might last only ten seconds but, symbolically, it marks the culmination of years of hard work.

Do you remember in the very early days of the pandemic—three years ago—we were instructed not to buy masks? Masks were in such short supply that health officials were concerned about their availability for professional providers and essential workers.[vi] Not long after that, whenever we did venture out of our homes, we wore masks. Early on, many were homemade. And then everyone was wearing masks. And now—for good or ill—masking is down significantly. Nevertheless, the masks continue to cross my path. Someday, however, we won’t see them on the ground either. But that doesn’t mean that things will be as we want them, following the admonition of Louise de Marillac, “for a long time to come.”

Perhaps it is simply an aspect of maturity that we grow to be more patient. But I do not mean to imply that patience is passive. Not at all. While we wait, we can move things along. We can find ways to respond to the conditions of our existence creatively. We can perception-check with others—what women in the second wave of feminism branded “consciousness-raising.” We can advocate.

In a blog post dated October 27, 2014, Father Ed Udovic describes the ceremony associated with the publication of the Congregation of the Mission’s Common Rules in 1658. He writes: “One of Vincent’s great gifts as a founder was his ability to take his time and through discernment and consultation draft and re-draft clear, concise, inspiring, essential, and useful rules based on faith and experience to guide his followers in the effective accomplishment of their mission to evangelize and serve the poor.”[vii] To further illustrate Vincent’s tacit acceptance of patience, it’s worth noting the Congregation was founded in 1625, and thirty-eight years passed before the Common Rules were published and distributed. It seems unlikely, however, that those who embraced the philosophy stated in those rules waited thirty-eight years to abide by their spirit.

What can we draw from Saint Vincent’s seeming embrace of patience as a method?

What are the challenges of life right now that provoke our impatience and a desire to move on too quickly?

How can we live in our liminal moments and embrace creative responses to uncertainty, whether individual or collective?

If this moment marks Covid’s threshold, what awaits us on the other side?

Reflection by: Jay B

[i] Letter 519, “To Sister Anne Hardemont (at Ussel),” (1658), Spiritual Writings of Louise de Marillac, 614–15. Available online at https://via.library.depaul.edu/ldm/.

[ii] Charles Tardy, “Counteracting Task-Induced Stress: Studies of Instrumental and Emotional Support in Problem-Solving Contexts,” in Communication of Social Support: Messages, Interactions, Relationships, and Community, ed. B. Burleson, T. Albrecht, and I. Sarason (New York: Sage Publications, 1994).

[iii] Craig Keller, “Unmasked,” DePaul Magazine, February 16, 2023, https://depaulmagazine.com/2023/02/16/unmasked/.

[iv] Victor Turner, The ritual process: Structure and Anti-Structure (De Gruyter, 1969).

[v] For Campbell, the “belly of the whale” is an initiation stage signifying death and rebirth (through digestion and the creation of new energy). Joseph Campbell, Hero with a thousand faces (Bollingen, 1949).

[vi] German Lopez, “Why America ran out of protective masks—and what can be done about it,” Vox, March 27, 2020, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/3/27/21194402/coronavirus-masks-n95-respirators-personal-protective-equipment-ppe.

[vii] Edward Udovic, “Saint Vincent’s Reading List LVIII: The Common Rules of the Congregation of the Mission,” The Full Text (blog), DePaul University Library, October 14, 2014, https://news.library.depaul.press/full-text/2014/10/27/saint-vincents-reading-list-lviii-the-common-rules-of-the-congregation-of-the-mission/.