This past weekend I was on a road trip with my wife back to our home town of Edmond, Oklahoma. As we drove the 12 hours cross-country to reach our destination, we passed through many different towns and cities. About 4 hours outside of Chicago we started to drive toward St. Louis. As we saw signs for SL and its surrounding suburbs my mother called to make sure I was safe.

“Safe?” I thought, “That is a strange thing for her to say.” Why would she be concerned for my safety when driving through a place like Missouri? Nothing ever seems to happen there.

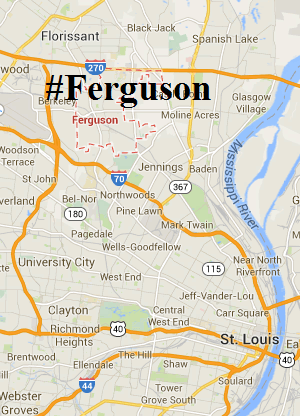

Then the name “Ferguson” flashed through my mind. I recalled the news stories, the social media posts. I thought of the news clips and images of police in full riot gear and armored vehicles roaming the streets of this small American town. I quickly took out my phone and asked my wife to look up the location of Ferguson MO.

“It’s on the other side of the state” I thought to myself. “It won’t have anything to do with me, or my short amount of time spent here in Missouri.” But lo and behold, Ferguson was fifteen minutes from our current location, just north of the city.

We see things on the news. We hear things on the radio. We engage with posts on facebook and twitter. We know about the world around us and events within an instant of their occurrence, but how often do we stop and think about its true effect on our lives?

The Middle East is so far away, how would anything going on there really have anything to do with us? Ebola virus, doesn’t that come from another continent? Darfur, Syria. How can I, living in my own little reality here in Chicago, have any connection with these events?

Herman Melville once said “We cannot live only for ourselves. A thousand fibers connect us with our fellow men…” But finding those fibers can be difficult at times. Sometimes it is realizing your location in regards to an event that opens the door. Ferguson is not far away. The people affected by this are not in a distant land, separated by oceans and mountains. These are my neighbors. These are our brothers and sisters and they are mothers and children who live only a small drive away. Who live next door. Unjust treatment of African Americans is happening all over America. All over my city. To my co-workers and to people living on my block.

One of the things I do to bond, to strengthen the fibers that link me with my fellow man, is educate myself. If you know about what is going on, then I think you start to care. So I say find ways to educate yourself about issues that concern you. Take the time to do your own research and don’t take for granted what one sources tell you – you have to shop around for the truth.

Secondly, I pray.

A rabbi once told me that Prayer is like clapping along to a song. It might not change the song itself. It does not fix the chorus you don’t like, or change the words, or alter the notes, but it allows you to actively engage with the song. When you clap, you are an active participant in the music, you engage on a personal level.

When we pray, we show that we are active participants in the world around us. We show ourselves that empathy and thought are crucial to how we see the world. Even if our prayers might not directly affect the outcome of a situation, we are there in spirit. We are joining the greatly collective of humanity that is hoping for peace and love in this world.

When I read, I understand. And when I pray, I empathize. Knowledge and empathy are the first steps to action. In writing this blog I am wondering where knowledge and empathy of the events of Ferguson and all over the nation can take me. I feel the need to act. How about you? Maybe knowledge and empathy will inspire you to sign a petition, join a march, call your legislators or share your knowledge with others. What to do and how to change the world we live in are up to us.

Matthew Charnay serves as DePaul’s Coordinator for Jewish Life.