In today’s turbulent world of polarizing opinions, how often do we find ourselves residing in echo chambers surrounded by those who think like us? This dynamic offers little opportunity to truly listen to and dialogue with others. What would it take to build bridges to greater understanding across the many divides that separate us today? And, how might a seventeenth-century French priest help us find our way?

As Margaret John Kelly writes, “Vincent de Paul changed history because he was a creative reconciler.”[1] In fact, because he “was able to successfully harness competing interests and make them work together in concrete ways for the service of the poor,” you are reading this reflection today in a university that bears his name and continues to be infused by his spirit.[2]

While Vincent lived more than four hundred years ago, parallels between his time and ours abound. During his lifetime, Vincent witnessed much national and international strife. He lived through the Thirty Years’ War and the civil war known as the Fronde. He also weathered numerous ecclesiastical controversies. Not unlike today, at that time, territorial rights were often the cause of much bloody conflict, and peace was more of a distant dream than a reality.

Seventeenth-century France was also beset by the overwhelming problem of “resettling refugees who were fleeing economic or political oppression, insufficient healthcare for the poor, a high level of unemployment, inadequate housing, and, of course, an astounding rate of malnutrition.”[3]

Like so many others, Vincent could have chosen to ignore the challenges of his age in favor of accepting the status quo, but he refused to accept the brokenness he saw around him. Instead, he committed his life to finding solutions to what may have seemed to be intractable problems. He used his keen imagination and a spirit of inventiveness to build what his heart longed to see: a more just world.

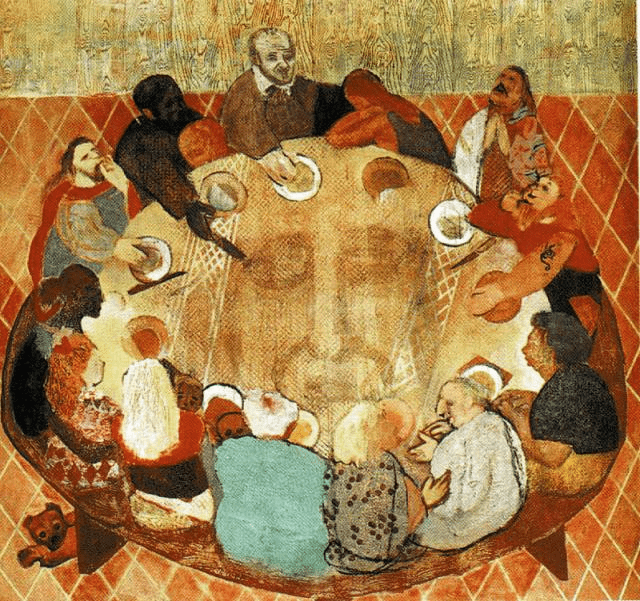

How did he do this? In addition to asking why such complex problems existed, Vincent would call upon the goodwill and wisdom of those around him to address them. Part of Vincent’s genius was that he knew he couldn’t engage these issues alone. He valued relationships and relied upon them to help reveal manifest sides of an issue, which he would have been unable to identify alone. Such a process involved gathering with others, including those with whom he disagreed, and painstakingly listening to diverse opinions with respect and dignity. It also required Vincent’s openness to being wrong. This method allowed Vincent to become more informed and, with others, to identify or create new possibilities.

Vincent’s North Star was always his faith in a loving God who calls for us to recognize and uphold the dignity of the other. Such a belief grounded all Vincent’s actions. Others around him, like Archbishop of Cambrai François de Fénelon, chose to “berat[e] the rich from the pulpit.”[4] But Vincent always insisted on the dignity of all, including royalty and the aristocracy. Rather than “otherizing” those with whom he may have disagreed, Vincent chose to steadfastly uphold the goodness of the human person. He would appeal to that goodness to serve the needs of the most marginalized. Indeed, Vincent’s ability to build bridges with the wealthy allowed him to “capitaliz[e] on their generosity” to serve the poor.[5] Through such networking and creative reconciliation efforts, he established myriad social development ministries, many of which exist to this day.

Today, when the challenges of our time feel overwhelming and risk obscuring the humanity of the other, Vincent’s voice still rings clear, inviting us to work for just and creative reconciliation against division.

Reflection Question:

As Margaret John Kelly notes, “The challenges of our day could lead us to despair or indifference; but we remember that our religious/political/social/economic environment is not unlike the one in which Vincent lived.”[6] These similar circumstances inspired Vincent’s quest for justice and creative reconciliation.

In what ways do you find yourself experiencing this call?

Reflection by: Siobhan O’Donoghue, PhD, Director of Faculty and Staff Engagement, Division of Mission and Ministry

[1] Margaret John Kelly, D.C., “Saint Vincent de Paul: A Creative Reconciler,” Vincentian Heritage Journal 12:1 (1991): 2. Available online at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol12/iss1/6.

[2] Untitled abstract to Kelly, ibid.

[3] Kelly, 4–5.

[4] Ibid., 12.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., 14.

On January 25 in celebration of

On January 25 in celebration of  Everyone within the DePaul community is encouraged to integrate this tradition across campus, whether through weekly meetings, gatherings or one-on-one settings. Recipients often f

Everyone within the DePaul community is encouraged to integrate this tradition across campus, whether through weekly meetings, gatherings or one-on-one settings. Recipients often f