“Nature makes trees put down deep roots before having them bear fruit, and even this is done gradually.”1

Over the next seven days we celebrate Vincent de Paul Heritage Week. This includes a series of events leading up to Vincent’s church-designated feast day on September 27th. These events are meant to invite the university community into a deeper reflection on our shared mission and heritage, which traces all the way back to seventeenth-century France.

When facing urgent and troubling challenges such as those of our present reality, you may ask why spend our time and energy remembering historical roots going back over 400 years? How do the words and actions of those who have preceded us and lived in such different contexts so long ago speak to us now? How can this focus on history help us to discern a meaningful and relevant mission for today?

Ultimately, whenever we reflect on our sense of mission, whether personal or institutional, we are asking: what is essential to who we are? Thinking about such profound questions may spark a religious, spiritual, or philosophical impulse in us, including a consideration of our origin stories. From where do we come and why were we created? Is there a purpose to our existence? If so, who are we called to be and what are we called to do? Storytelling traditions surrounding the origins of communities of people have been common since the dawn of humanity. These stories often help us to hold and communicate values, meaning, purpose, and a sense of connectedness with one other, as well as to engage present-day circumstances with a deeply formed sense of identity.

We have a storytelling tradition at DePaul University. It is passed on within the history of the Congregation of the Mission and all those in the Vincentian family who live and sustain our shared, foundational mission rooted in the lives of Vincent de Paul and Louise de Marillac. Over his many years at DePaul, Vincentian historian, Fr. Edward R. Udovic, C.M., often reminded us that in order for the lessons of history to be meaningfully re-contextualized for today, we must first understand the historical background from which these gifts emerged.

In other words, our efforts today to be rooted in and clarify our common mission as an institution comes with a two-fold responsibility. First, we must continually seek to better understand the historical roots and foundational stories of the Vincentian family, which ultimately gave birth to DePaul University. Second, we must seek to faithfully discern how those roots can be extended creatively and effectively to sustain our lives and work today. This is so even considering that the current challenges and opportunities we face could never have been imagined by Vincent de Paul hundreds of years ago.

The roots that have sustained our Vincentian tradition over time are characterized by a generous and caring spirit, essential to both historical and modern-day Vincentian communities, religious and lay. It is a spirit that focuses its efforts and attention on the service of those in society who are most in need. It asks critical questions about who is being left out or marginalized and seeks to affirm their dignity. It is a spirit that works to change social, economic, and political systems for the better.

When we reflect upon our Vincentian heritage this week, we do so with great humility, a virtue many recognized in Vincent de Paul. We do so with a willingness to acknowledge how far we still must go to live up to the deep, time-tested ideals that urge us forward. We take heart in knowing we are not alone on this journey. In fact, we join the decades and centuries old caravan of those who have also taken the Vincentian spirit to heart and sought to improve the lives of others.

To be Vincentian is to ask, as Madame de Gondi did of Vincent de Paul, “What Must be Done?” It is to get up day-after-day and continue our mission by taking concrete action. In times like these that challenge society and our institution, we are indeed fortunate for the deep roots of our mission.

Reflection Question:

How do the deep roots of our Vincentian mission and story inform your approach to today’s challenges?

1 1796, To Charles Ozenne, Superior, In Warsaw, Paris, 13 November 1654, CCD, 5:219.

Reflection by Mark Laboe, Associate VP for Mission and Ministry

See all the Vincent de Paul Heritage Week Events

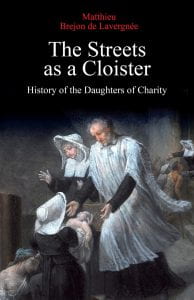

The Vincentian Studies Institute is extremely pleased to promote the publication of our colleague and fellow board member’s new work. Dr. Brejon de Lavergnée is a Professor of History and the Dennis H. Holtschneider Chair of Vincentian Studies at DePaul University.

The Vincentian Studies Institute is extremely pleased to promote the publication of our colleague and fellow board member’s new work. Dr. Brejon de Lavergnée is a Professor of History and the Dennis H. Holtschneider Chair of Vincentian Studies at DePaul University.