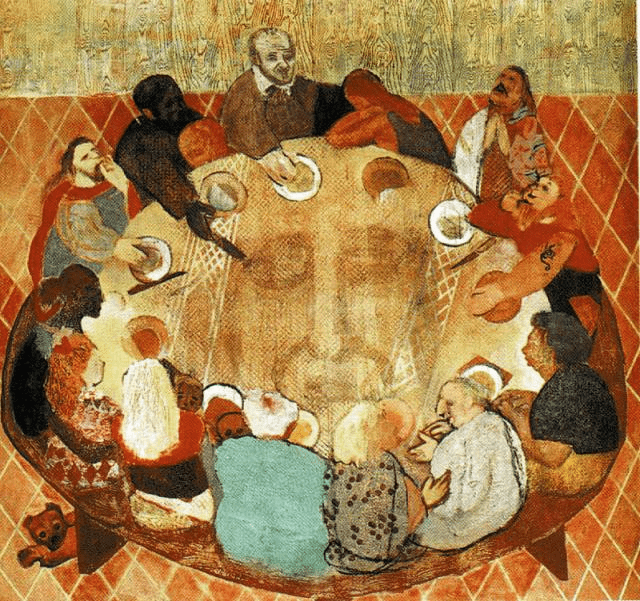

What a blessing to be a member of a Community because each individual shares in the good that is done by all!”[1]

I have been thinking a lot lately about community—what it means, what it looks like, and why it is so essential to us as human beings and as a university, especially in our current context. Looking back on past Mission Monday reflections, it is clearly not the first time I have felt this to be important to identify as an essential focus for an organization like ours that seeks to embody the Vincentian name.

Yet, there are many reasons for the need to re-emphasize the importance of community at this time:

- the ongoing changes we are moving through as a university community, including the loss of many longtime friends and colleagues;

- the marked increase in colleagues working from home since the pandemic;

- the concurrent loss of regular face-to-face interactions in common spaces;

- the larger cultural divisions and inequities in our society that only linger if not addressed directly;

- the growing tendency among many to connect with each other and to learn only or primarily via computer or smartphone; and

- recent public reporting on the rise and deleterious impact of loneliness in U.S. society.

Each of these changes—and there are clearly others—has recently had drastic effects on workplace norms and workplace culture within the patterns of our lives and relationships at DePaul.

Perhaps this draw to focus again on the importance of community also simply reflects my own experience and ongoing hunger for human connection, to feel a sense of belonging, and to participate in something more beyond the daily tasks of my individual work.

Regardless of the source of my musings, I am certain I am not alone. The experience of being part of a community is important for the well-being of humanity and for the flourishing of our workplaces, including and especially our university. Furthermore, here at DePaul, many rightly appreciate the experience of community as being “very Vincentian.”

In fact, how we sustain and continue to build a vibrant communal life is one of the vital, open questions facing us today. Over my eighteen years at DePaul, I believe the intentional work and effort of building community, and the need for it, has never been more important and more at risk. As we look ahead to the summer and the coming academic year, it is essential that we continue to weave and re-weave with great intention and care the fabric of our communal life if our Vincentian mission is to be effective and sustained over time.

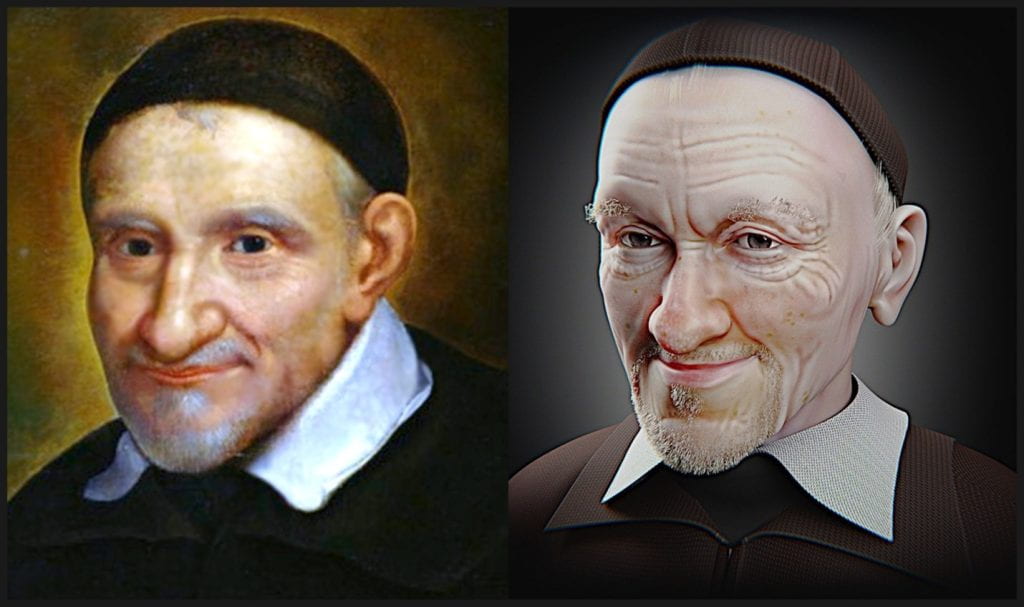

I am fond of imagining Vincent de Paul in Folleville, France, in 1617 and what must have been going through his mind at that time. Based on his own retrospective reflections, that particular year and place seemed to represent an important moment in his life, a moment when, with the help of Madame de Gondi, Vincent arrived at a clearer vision of his own calling and the mission that God had entrusted to him.

The year 1617 was the final feather falling on the scales that tipped the orientation of Vincent’s life in a markedly different way. The upwardly mobile and aspirational priest, often rubbing elbows with the rich and powerful, began to focus his energies more and more toward a mission of service to and with society’s poor and marginalized for the remainder of his life. What he realized at that same time is that the mission God had entrusted to him was much bigger than he alone could fulfill. He needed others. In fact, Vincent’s effectiveness grew largely through the work of inspiring and organizing others to work in common to fulfill a shared mission. From the beginning, the Vincentian mission has been a collaborative and communal enterprise.

Simple in its genius, Vincent’s efforts anticipated current day organizational management insights by 400 years. The contemporary organizational and business writer and consultant Christine Porath, for example, has written extensively on how community is the key to companies moving from merely surviving to thriving together.[2] Simply put, her research suggests that when people experience a strong sense of community and belonging at work, they are more engaged, effective, healthy, and creative. This, in turn, leads to positive business outcomes. Many other organizational and business leaders have come to similar conclusions. It turns out that how we relate to each other as a community in the workplace, in fact, matters a great deal.

At DePaul, we speak often of being “a community gathered together for the sake of the mission.” We recognize and must remember that we need each other to thrive. Faculty, staff, administration, students, board members, alumni and donors work together effectively for a shared mission. Furthermore, as Vincent de Paul suggests, we each benefit from the good done by all. At our best, when we are flourishing as a community, we help, encourage, care for, collaborate with, and inspire one another. There is an energizing and vibrant unity that comes in our diversity—the unity of a shared mission to which each person contributes a part. This occurs only through ongoing intentionality and thoughtful daily interactions and efforts to build and sustain healthy and vibrant relationships with one another.

As we move into the summer months, through the many changes we are facing together, and into the new academic year this fall—this is your charge: How will you contribute to sustaining and building a vibrant and healthy sense of community together with your DePaul colleagues?

Submit your own recommendations as a response to this blog post or follow our Mission and Ministry LinkedIn group, which we will begin to use more often in the future as a place to share reflections on the workplace in light of anticipated changes with DePaul Newsline in the summer and the coming year. Perhaps by the time a new academic year begins, we can initiate some new efforts to weave or re-weave the fabric of our communal life and work intentionally toward thriving as “a community gathered together for the sake of the mission,” just as Vincent de Paul first envisioned.

Reflection by: Mark Laboe, Associate VP, Mission and Ministry

[1] Conference 1, “Explanation of the Regulations,” July 31, 1634, CCD, 9:2. Available at https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentian_ebooks/34/.

[2] See: Christine Porath, Mastering Community: The Surprising Ways Coming Together Moves us from Surviving to Thriving (New York: Balance Books, 2022); and C.M. Pearson and C.L. Porath, The Cost of Bad Behavior: How Incivility Is Damaging Your Business and What to Do About It (New York: Portfolio, 2009).