Written By: Siobhan O’Donoghue, M. Div., Director of Faculty and Staff Engagement, Mission & Ministry

“When the roots are deep, there is no reason to fear the wind.” Drawing on the wisdom of such a profound African proverb, Julianne Stratton, Lieutenant Governor of Illinois and DePaul alum, thus began a recent reflection at DePaul. Along with Valerie Johnson, associate provost for diversity, equity, and inclusion, and Dania Matos, vice president for diversity, inclusion, and belonging, Stratton was serving on a panel to discuss the challenges and opportunities facing higher education today. As part of the President’s Dialogue series, all three panelists emphasized the importance of community and leaning into our mission at an uncertain time. This is even more important when some of our core values may feel under attack. “So, for now, do what you’ve been doing, maintain your mission, understand why it’s important. We’ll get through this together.” [1]

“When the roots are deep, there is no reason to fear the wind.” Drawing on the wisdom of such a profound African proverb, Julianne Stratton, Lieutenant Governor of Illinois and DePaul alum, thus began a recent reflection at DePaul. Along with Valerie Johnson, associate provost for diversity, equity, and inclusion, and Dania Matos, vice president for diversity, inclusion, and belonging, Stratton was serving on a panel to discuss the challenges and opportunities facing higher education today. As part of the President’s Dialogue series, all three panelists emphasized the importance of community and leaning into our mission at an uncertain time. This is even more important when some of our core values may feel under attack. “So, for now, do what you’ve been doing, maintain your mission, understand why it’s important. We’ll get through this together.” [1]

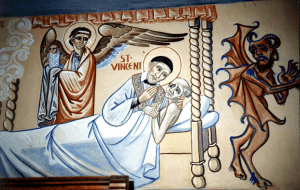

During his lifetime, Vincent de Paul also often encountered attacks on some of the core values and beliefs upon which his life and ministry were grounded. This was especially true during the War of Great Confinement, [2] which was a time when more than five thousand poverty-stricken individuals were institutionalized for the crime of being poor.

Specifically, in the words of a decree established by the State:

We expressly prohibit and forbid all persons of either sex, of any locality and of any age, of whatever breeding and birth, and in whatever conditions they may be, able-bodied or invalid, sick or convalescent, curable or incurable, to beg in the city and suburbs of Paris, neither in the churches, nor at the doors of such, nor at the doors of houses nor in the streets, nor anywhere else in public, nor in secret, by day or night … under pain of being whipped for the first offense, and for the second condemned to the galleys if men and boys, banished if women or girls. [3]

Almsgiving was also prohibited at this time. Indeed, those who were poor without anywhere to hide or escape were considered enemies of the state. Accordingly, they were hunted down by the Parisian militia, commonly known as the “archers of the poor,” [4] and forced into mandatory institutions of the General Hospital of Paris.

Yet amid such turmoil, the call of Vincent and Louise remained clear and their response undaunted: to “defend, honor and lovingly serve the most abandoned of the poor.” Thus, they, along with the confraternities and institutions that they had founded, continued to administer charity to the most abandoned, despite the challenges they faced during this tumultuous time.

Centuries later, in Chicago in 1898, while the context was very different, a similar impetus would prompt the Vincentians to establish Saint Vincent’s College. Since education was seen as a way to help families out of poverty, the Vincentian purpose was clear. To educate “the sons of Chicago’s burgeoning Catholic immigrant population.” [5] This establishment would lead to the diverse and vibrant university we know as DePaul today.

And now, every month, the Division of Mission and Ministry helps orient an array of new staff to the university. An integral part of this orientation is to reflect together on some of the milestones along our Vincentian path of 430+ years. As a regular facilitator of these orientations, I am always amazed at how, while the terminology we use to describe DePaul’s core values has evolved, the values themselves have not changed. Our commitment remains steadfast. In our essence, DePaul remains a Catholic, Vincentian institution that strives to genuinely welcome and serve diverse faculty, staff, and students, inviting each person to become part of a values-based learning community that is inclusive and accepting. [6] This creates a true sense of belonging for all, grounded in a deep respect for human dignity. Such a commitment is part of a living legacy, of which we are all part. Indeed, as Vincent and Louise might have attested, “Plus ça change, plus c’est la meme chose,” or, in more familiar terms, “The more things change, the more they remain the same.”

Reflection Questions

- What do you value most about working at DePaul?

- In what ways do you identify with these values of Sts. Vincent and Louise?

Reflection by: Siobhan O’Donoghue, M. Div., Director of Faculty and Staff Engagement, Mission & Ministry

[1] Russell Dorn, “DePaul Hosts Illinois Lieutenant Governor Juliana Stratton for Dialogue on Building Belonging,” March 3, 2025, DePaul University Newsline, at: https://resources.depaul.edu/newsline/sections/campus-and-community/Pages/building-belonging-25.aspx.

[2] See Edward R. Udovic, C.M., “‘Caritas Christi Urget Nos’: The Urgent Challenges of Charity in Seventeenth-Century France,” Vincentian Heritage 12:2 (1991): 86. Available online at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol12/iss2/1/.

[3] Ibid., 85–86.

[4] Ibid., 101.

[5] Dennis P. McCann, “The Foundling University: Reflections on the Early History of DePaul,” in DePaul University Centennial Essays and Images, ed. John L. Rury and Charles S. Suchar (Chicago: DePaul University, 1998), 52. Available online at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentian_ebooks/20.

[6] Edward R. Udovic, C.M., “Vincentian Pilgrimage Hospitality: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives,” Vincentian Heritage 33:1 (2016). Available online at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol33/iss1/4.