It’s likely that in the midst of some recent clerical task, most of us have wondered: What is the point of all this? How can I be asked to go about the daily mundane responsibilities of my job in the face of all that is going on in the world? In the face of war, of plague, of hunger and violence? When people are killed because of the color of their skin, or when people are killed for no discernible reason at all, including precious and innocent children in school with their teachers?

It’s likely that in the midst of some recent clerical task, most of us have wondered: What is the point of all this? How can I be asked to go about the daily mundane responsibilities of my job in the face of all that is going on in the world? In the face of war, of plague, of hunger and violence? When people are killed because of the color of their skin, or when people are killed for no discernible reason at all, including precious and innocent children in school with their teachers?

The particular wars and other great events of our time chronicled in the news or on our social media feeds demand our immediate attention, and many strike home. Massive student debt and a widespread mental health crisis related to inadequate healthcare force us to think deeply about the role of higher education in our time and place. Above all these immediate calamities, the long-term environmental crisis calls to us as well. Serious people ask if having children in the face of these realities is even responsible or ethical.

I was recently introduced to a remarkable sermon that was given by C. S. Lewis in October 1939, less than two months after the invasion of Poland and Britain’s entry into World War II. He called it “Learning in War-Time.”[1] Lewis begins by asking his Oxford audience whether the study of academic subjects, the work of a university, is “an odd thing to do during a great war.” Unsurprisingly to those familiar with his work, Lewis’s own answer to this question is a profoundly eloquent Christian one. The essential point Lewis makes is one that can resonate with any one of us, regardless of the nature of our particular faith or lack thereof: the calamities of our time do not essentially change the nature of our predicament as humans; they only bring it into stark relief. They are disillusioning in the positive sense. They take away illusions that prevent us from seeing clearly. We are all mortal, and our lives are short—our task is to fill our lives with meaning.

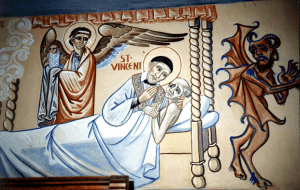

Vincent DePaul was also no stranger to such existential questions; his seventeenth-century France was a place of frequent war, plague, and desperate poverty. We often tell the story of how Vincent found his mission, his true calling, at the bedside of a dying peasant who was racked with guilt over unconfessed sins and whose soul was liberated by the pastoral accompaniment of Vincent in that moment.[2]

We each have to discern our own calling, our own mission. Prior to his encounter with the peasant, Vincent’s life was about seeking worldly success and upward mobility from his own Gascon peasant background. There was no shame in this, and no shame if that is the focus of many students we serve here at DePaul. Yet there can be an invitation to something greater, to a calling that truly makes sense to pursue in any situation. Once you connect with that greater vision, you can approach any work that you do, regardless of how mundane it may seem to others, in light of the vital role it plays in a greater task of epic importance. It will make sense to you even in times of war, of plague, and of hunger.

Do you see your daily work as part of a larger calling or mission? A way to support and care for your family? Do you connect with and are you inspired by the shared Vincentian mission of DePaul? What can you do to ensure that whatever you are doing is meaningful?

Reflection by: Abdul-Malik Ryan, Assistant Director, Religious Diversity and Pastoral Care, and Muslim Chaplain.

[1] C. S. Lewis, “Learning in War-Time,” at: https://www.christendom.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Learning-In-Wartime-C.S.-Lewis-1939.pdf.

[2] Edward R. Udovic, C.M., Ph.D., “History of the Church at Folleville,” The Way of Wisdom (blog), DePaul University, March 31, 2018, at: https://blogs.depaul.edu/dmm/2018/03/31/history-of-the-church-at-folleville/; Andrew Rea, “The 400th Anniversary of St. Vincent de Paul’s Sermon at Folleville,” The Full Text (blog), DePaul University Library, January 25, 2017, at: https://news.library.depaul.press/full-text/2017/01/25/4809/.