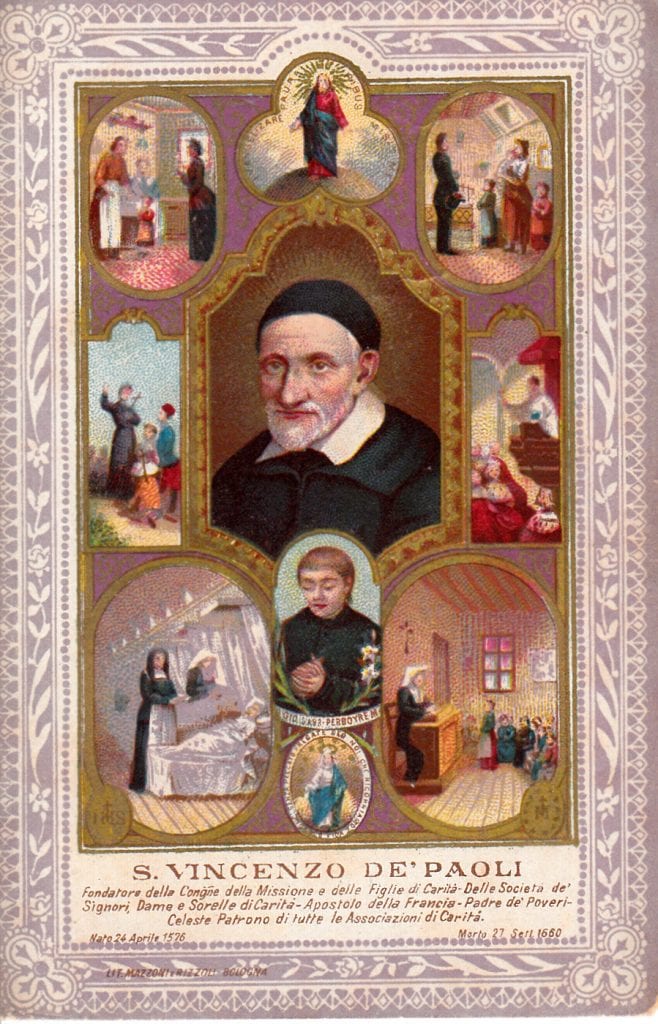

The Vincentian Studies Institute recently acquired this Italian holy card for its collection. Dating from the late 19th or early 20th century (after the beatification of Jean-Gabriel Perboyre in 1893) it is a very early example celebrating the wider Vincentian Family including the Congregation of the Mission, the Daughters of Charity, the Ladies of Charity, the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, and the Sisters of Charity. Louise de Marillac is also featured.

Holy Card

Book of the Week: “La douceur du roi. Le gouvernement de Louis XIV et la fin des Frondes 1648-1661.”

Nina Brière, La douceur du roi. Le gouvernement de Louis XIV et la fin des Frondes 1648-1661, Laval: Presses de l’Université Laval, 2011), pp. 172. ISBN: 978-2-7637-9392-4.

Paris, 2 juillet 1652. Pour échapper à ses assaillants, Louis II de Bourbon, prince de Condé, accompagné de ses troupes, parvient à entrer dans la ville in extremis. Le sang sur son armure est celui des soldats de son proper cousin, Louis XIV, roi de France. Depuis près de quatre ans, plusieurs grands membres de la noblesse française se sont révoltés contre le gouvernement royal. Ils en veulent plus particulièrement à Jules Mazarin, successeur du cardinal de Richelieu et principal ministre du royaume. Pour tenter de la chaser, ils s’allieront aux Espagnols, ennemis des Français. Cette révolte complexe qui secoua la France s’appelle la Fronde. De 1648 à 1653, plusieurs groups de la société française prennent les arms et bravent l’autorité royale. Le gouvernement de Louis XIV devra mater la révolte. De quelle façon s’y prendra-t-il? L’image du roi que nous lègue l’histore est un être dur et sans pitié. Et s’il en était autrement? Considéré comme le père du people, le roi de France pouvait-il se permettre de réprimer dans le sans ses sujets revoltés?

NINA BRIÉRE est née à Lahr, en Allemagne, en 1983. Après quelques allers-retours entre l’Europe et la Canda jusqu’à la fins des années 1990, elle entame ses études supérieurs au Québec. Son baccalauréat en histoire avec profil international à l’Université Laval terminé, elle poursuit à la maîtrise en histoire politique sous la direction de Michel de Waele, specialiste de l’Europe à l’époque moderne. Elle s’intéresse à la resolution des conflits et aux strategies politiques dans la France du XVIIe siècle.

Footnote: The Relics of Saint Vincent de Paul During the French Revolution

Paul Pisani, L’Église de Paris et la Révolution (Paris: Picard, 1908). 4 vols.

An interesting note with respect to St. Vincent’s relics during the French Revolution is found in Volume 3, pg. 377

“Le 19 juillet 1797, M. Dubois, qui etait Lazariste, voulut donner une solennité extraordinaire à la fête de Saint-Vincent-de-Paul. Il y eut un concours immense de fidèles; 200 prêtres assistaient à la cérémonie qui présida l’évêque de Saint-Papoul; l’abbé de Boulogne fit le panégyrique du saint, si populaire à Paris, et l’éotion fut à son comple quand il annonca du haut de la chaire que le coprs de saint Vincent de Paul, qu’on avait cru profane et détruit, avait été enlevé par les prêtres de la Mission, et, encore, muni de tous les sceauz qui l’authentiquaient, depose, dans un lieu sûr, en attendant le jour où la Providence méagerait des circonstances favorable pour l’exposer de nouveau à la veneration des fidèles.”

Saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre: September 11th Feast Day

The Vincentiana material culture collection at DePaul University has a wide variety of Vincentian holy cards in its collection including this selection of Jean-Gabriel Perboyre holy cards.

Additional Rosalie Rendu Holy Cards

The Vincentiana material culture collections at DePaul University also have acquired the two following two examples of early Rosalie Rendu holy cards. The first is a very early “Bonne Soeur Rosalie” pose. We believe this image to be one of the earliest portrayals of Rosalie in existence. The second image dates from later in the 19th century and features the very familiar portrait by Riffaut.

Early Rosalie Rendu Holy Card

The Vincentiana Collection at DePaul University recently purchased this very early holy card depicting a scene from the life of Rosalie Rendu. This incident took place during the revolution of 1848. Sr. Louise Sullivan has an account in her biography of Rosalie on pages 179-180. The card does not name Sr. Rosalie, but it depicts her historical role in this incident. The card certainly dates to within years of the event. The back of the card has this description (translated from the French).

“It is in times of trials and terror that the sublimity of religion is clearly revealed in the devotion of its ministers and its virgins. While in the faubourg Saint-Antoine the venerable prelate of the capital (Msgr. Affre the archbishop) gave his life for his sheep, in the Saint-Marceau district an officer of the national guard was saved by the devotion of the daughters of Saint Vincent de Paul. He took refuge among them to escape his pursuers from among the insurgents. However, when he heard the death threats that these men made against these holy women he gave himself up to his furious pursuers despite the sisters’ pleas. He was grabbed, forced to his knees, and was about to be executed. At this moment, the courageous superior ignored the threats of the malefactors and placed herself between them and their intended victim. She said to them: “This is the house of God, and you will not soil it by this crime! For 45 years I have served you, and for the first time I ask you for something in return. Can you refuse me?” Then one of these men put his bayonnet to the throat of another of the sisters and said: “Well then, it is you who will be killed.” “Do you think I am afraid of your bayonette?” said the courageous virgin to him. She responded with disdain. “It is God alone that I fear.” How can one not recoginze the divinity of a religion which engenders such sublime devotion!”

VHRN Book of the Week

Alain de Solminihac (1593-1659). Prélat réformateur de l’Abbaye de Chancelade à l’évéché de Cahors. By Patrick Petot. 2 vols. [Bibliotheca Victorina, Vol. XXI.] (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009. Pp. 507; 509-1091. €140,00. ISBN 978-2-503-53277-6.)

Alain de Solminihac (1593-1659). Prélat réformateur de l’Abbaye de Chancelade à l’évéché de Cahors. By Patrick Petot. 2 vols. [Bibliotheca Victorina, Vol. XXI.] (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009. Pp. 507; 509-1091. €140,00. ISBN 978-2-503-53277-6.)

From the publisher:

Abbé de Chancelade en Périgord et évêque de Cahors, Alain de Solminihac (1593-1659) est une figure marquante du mouvement de réforme pastorale de l’époque baroque.

Formé à Paris, il entreprend en 1623 le relèvement spirituel et matériel de son abbaye de Chancelade qui devient, en moins d’une décennie, un centre à partir duquel la réforme canoniale s’étend à la Saintonge, au Limousin et à l’Angoumois. Cette extension se heurte à la volonté du cardinal de La Rochefoucauld et de Charles Faure qui transforment la congrégation de Sainte-Geneviève en une congrégation de France destinée à regrouper dans une organisation centralisée toutes les branches de l’ordre canonial. Au terme d’un long conflit, dont les étapes sont ici reconstituées, la réforme de Chancelade n’échappe à l’absorption qu’au prix de l’abandon de son expansion.

La carrière de l’abbé de Chancelade connaît un tournant majeur avec sa nomination à l’évêché de Cahors en 1636. Religieux devenu évêque, il transpose son idéal de perfection chrétienne dans l’état épiscopal et entreprend la réforme de son diocèse selon le modèle tridentin et l’exemple de Charles Borromée : reconstitution du patrimoine épiscopal, statuts synodaux, mise en place de vicaires forains, visites pastorales, missions prêchées par les chanoines réguliers qu’il a amenés avec lui de Chancelade, fondation d’un séminaire confié aux prêtres de la Mission. Cette ferme action réformatrice s’est durablement heurtée à une opposition cléricale organisée.

Son rôle déborde largement son abbaye et son diocèse. Comte de Cahors et baron de Quercy, Solminihac appuie de son autorité temporelle le pouvoir royal durant la Fronde. Influent dans l’Église de France, étroitement lié à Vincent de Paul, membre de la Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement, il joue un rôle important dans les affaires du temps, qu’il s’agisse de défendre les prérogatives du Saint-Siège, de condamner l’Augustinus ou d’obtenir la nomination d’évêques conformes à son idéal tridentin.

Ancien élève de l’École normale supérieure, agrégé de l’Université et docteur en histoire, Patrick Petot est professeur de classes préparatoires à Périgueux. Il s’est spécialisé dans la recherche en histoire religieuse et dans l’étude comparée des religions.

Reviewed by Alison Forrestal: The Catholic Historical Review, April, 2011, Vol. XCVII, No. 2,

Leads – Ozanam and the roots of See-Judge-Act

Here are highlights of what I have come up with so far…

▼ Philosophical Father of the See-Judge-Act Another Ozanam

• http://www.olle-laprune.net/philosopher-of-the-see-judge-act

• Léon Ollé-Laprune can be considered, along with Alphonse Gratry from whom he drew inspiration, as one of the key philosophers of Marc Sangnier’s Sillon movement and later of the YCW movement founded by Joseph Cardijn.

Cardijn read the philosophy of Léon Ollé-Laprune as a young seminarian, Indeed, this influence is evident as soon as you start reading the works of Léon Ollé-Laprune.

Born in Paris in 1839, Léon Ollé-Laprune was a brilliant student at the Ecole Normale Supérieure where he would later become maître de conférences in 1875, a position he held until his premature death as a result of appendicitis on 13 February 1898.

He was much influenced by Frédéric Ozanam, who is most well known as founder of the Saint Vincent de Paul Society, but was also a pioneer supporter of the workers democracy founded after the February Revolution of 1848. Ozanam had also been a lecturer in the French university system and it was his Christian commitment lived out in his lay life which most influenced Léon Ollé-Laprune.

As mentioned, Léon Ollé-Laprune’s philosophy drew heavily on the work of Alphonse Gratry, another democrat of 1848.

▼ Léon Ollé-Laprune and the Sillon

• Léon Ollé-Laprune and his family were also close to the parents of the young Marc Sangnier and it is evident that the philosopher had a great influence on the founder of the Sillon movement. Indeed, Albert Lamy, also from the Sillon, wrote of Léon Ollé-Laprune, that “sa philosophie de la vie est la nôtre”, his philosophy of life is our philosophy.

In fact, in a small virtually forgotten book, Les Sources de la Paix Intellectuelle (The Sources of Intellectual Peace) published in 1892, Ollé-Laprune discussed the need to build a “movement” based around the idea that everyone has “quelque chose à faire dans la vie”, that each person has “something to do in life” as a co-operator of God.

Marc Sangnier and a number of students at the Stanislas University College in Paris were the first to take up this challenge of building such a movement dedicated to enabling people to discover their lay mission in the world in this way. Originally known as the Crypt, their group later adopted the name, Le Sillon (The Furrow) for their soon to be famous movement.

▼ Léon Ollé-Laprune and the See, Judge, Act method

• Although it was Cardijn who formulated the famous expression “see, judge, act” it was Léon Ollé-Laprune who was mainly responsible for developing the philosophical theory that lay behind the method.

In fact, the foundation of the see-judge-act method had already been developed by Léon Ollé-Laprune’s neighbour, Frédéric Le Play, the pioneering social scientist. Le Play’s méthode d’observation sociale formed the basis of the enquiry method later adopted by the Sillon, the YCW and other lay apostolate movements. Le Play, however, held to an elitist, paternalist conception of social organisation as indicated by the subtitle of his famous work La Méthode Sociale, “ouvrage destiné aux classes dirigeantes” (a study addressed to the ruling classes).

Léon Ollé-Laprune rejected Le Play’s elitist conception of society in favour of a democratic ideal. Ollé-Laprune’s writings thus developed a notion of the “moral person” acting in the world based on Aristotle’s conception of prudence (Phronesis – a much broader concept than the modern understanding of prudence) as the virtue necessary for political leader.

Ancient Greek democracy, however, had been restricted to the elite. Ollé-Laprune saw that a modern democratic society reqiured that every citizen needed to develop the level of prudence necessary for participating in governance. For Ollé-Laprune, prudence therefore became the democratic virtue and education for democracy was necessary to foster the growth of the ‘moral person’ as a responsible citizen.

Marc Sangnier’s Sillon movement took up the challenge of building the necessary movement of democratic education, a notion later adapted by Cardijn as the basis of the worker education methodology of the YCW.

Léon Ollé-Laprune’s philosophy therefore lies at the heart of the YCW method and he can therefore justly be considered as the philosophical father of the See, Judge, Act.

▼ Alphonse Gratry, Mystic and reformer

• Alphonse Gratry, the 19th century French priest, mystic and philosopher, was a major source of inspiration for the young Joseph Cardijn.

Born in 1805, Gratry became a leading figure of the first generation of Christian social action in the period before and after the Workers Revolution of 1848. He was close to Frédéric Ozanam, who he brought in as a lecturer at the Stanislas College in Paris of which Gratry was director in the 1840s. After the death in 1854 of the excommunicated priest, Félicité de Lamennais, it was Gratry who celebrated a mass in his memory. He also knew Frédéric Le Play, the pioneering social researcher, whose methods were later adapted first by the Sillon and later by the YCW in its see-judge-act method. As John Henry Newman had done in England, so too in France did Gratry restore the Oratory, an association of priests founded by St Philip Neri. In short, Alphonse Gratry was a towering personality but whose influence always remained somewhat in the background.

He wrote a number of books, including a manual of social action published during the 1848 revolutionary period. Later his works took a more philosophicala and theological bent. His book, Les Sources, became an important reference for spiritual direction. His last book, La Paix, which was published in 1869, just before the outbreak of the Franco-German war of 1870, caused a storm in the militaristic ruling circles who dominated French political life.

Gratry opposed the definition of papal infallibility at the first Vatican Council. He was perhaps a major influence in the prevention of a broader definition from being adopted at the Council. After a period of reflection, he finally adhered to the teaching of Vatican I shortly before his death, preferring not to isolate himself or cut himself off from the Church as Lamennais had done.

His writings would later become an important source for the second generation of modern lay apostolate leaders and thinkers. The philosopher, Léon Ollé-Laprune, himself a disciple of Ozanam, nevertheless placed Gratry on a pedestal even higher than that of the founder of the Society of St Vincent de Paul. Gratry’s writings, together with those of Ozanam and Ollé-Laprune, would also be greatly influential with Marc Sangnier and his collaborators in the foundation of the Sillon in the Crypt of Stanislas College in the 1890s.

Gratry exercised a wide influence at the end of the 19th century. The philosopher, William James, who wrote extensively on the philosophy of religious experience, and whose writings were also read by the young Cardijn, was one of many who were influenced by Gratry.

Like his predecessors, Cardijn also drew heavily on the writings of Alphonse Gratry, who thus became a vital source for the development of the third generation of the modern lay apostolate.

Alphonse Gratry’s thought would also become an important source for the recently canonised philosopher, St Edith Stein. Other social movements also drew on his thinking, e.g. the Moral Rearmament movement begun at Oxford in the 1930s.

Another to be influenced by Gratry was the English mathematician and philosopher, George Boole in whose honour we today speak of boolean logic.

In recent times, Gratry’s work has been been largely forgotten.

However, the late Spanish philosopher, Julian Marias, published a book, La Filosofía del padre Gratry.,

And in 2006, the French Oratorians and the Cercle du Sillon hosted a colloquium at the French Senate, where Gratry had been chaplain, to mark the 200th anniversary of his birth;

Other recent references to Gratry can be found by searching by a (Boolean!) search on altavista or another search engine.

▼ Wikipedia

• http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%C3%A9on_Oll%C3%A9-Laprune

• As Frédéric Ozanam had been a Catholic professor of history and foreign literature in the university, Ollé-Laprune’s aim was to be a Catholic professor of philosophy there. Theodore de Regnon, the Jesuit theologian, wrote to him:

“I am glad to think that God wills in our time to revive the lay apostolate, as in the times of Justin and Athenagoras; it is you especially who give me these thoughts.”

The Government of the Third Republic was now and then urged by a certain section of the press to punish the “clericalism” of Ollé-Laprune, but the repute of his philosophical teaching protected him. For one year only (1881-82), after organizing a manifestation in favour of the expelled congregations, he was suspended from his chair by Jules Ferry, and the first to sign the protest addressed by his students to the minister on behalf of their professor was the future socialist deputy Jean Jaurès, then a student at the Ecole Normale Supérieure.

The Academy of Moral and Political Sciences elected him a member of the philosophical section in 1897, to succeed Vacherot. Some months after his death William P. Coyne called him “the gre

Tracing the impact of Frederic down to “See – Judge – Act”

I recently had occasion to do some research on Frederic’s social thought.

I knew he had anticipated both Karl Marx’ Manifesto and Leo” XIII’s Great Social encyclical “Rerum Novarum”

I was surprised to learn the the “See – Judge – Act” methodology of Cardinal Cardijn can be traced back in some degree to Ozanam.

The lineage runs something like this….

“Although it was Cardijn who formulated the famous expression “see, judge, act” it was Léon Ollé-Laprune who was mainly responsible for developing the philosophical theory that lay behind the method.”

But Ollé-Laprune was himself of disciple of Ozanam.

Are there any English-speaking researchers who are working with this development?

Also it is claimed that Leo XIII was greatly influenced by a member of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul. Anyone working on this.

VHRN Book of the Week

Church, Society, and Religious Change in France, 1580-1730 by Joseph Bergin

Church, Society, and Religious Change in France, 1580-1730 by Joseph Bergin

Yale University Press, 2009, 506 p

ISBN: 9780300150988

Winner of the 2010 Me du concours des antiquites de France given by the Academie des Inscriptions et Belles’Lettres in Paris

This readable and engaging book by an acclaimed historian is the only wide-ranging synthesis devoted to the French experience of religious change during the period after the wars of religion up to the early Enlightenment. Joseph Bergin provides a clear, up-to-date, and thorough account of the religious history of France in the context of social, institutional, and cultural developments during the so-called long seventeenth century.

Bergin argues that the French version of the Catholic Reformation showed a dynamism unrivaled elsewhere in Europe. The traumatic experiences of the wars of religion, the continuing search within France for heresy, and the challenge of Augustinian thought successively energized its attempts at religious change. Bergin highlights the continuing interaction of church and society and shows that while the French experience was clearly allied to its European context, its path was a distinctive one.

Joseph Bergin is professor of history at the University of Manchester, and a Fellow of the British Academy. His previous books include Cardinal Richelieu, The Making of the French Episcopate and Crown, Church and Episcopate under Louis XIV, all published by Yale.

Reviews:

An authoritative account of the French church in the ‘long seventeenth century’ that is both general and nuanced. We certainly need a book on this subject and Joseph Bergin is unquestionably the historian to write it.” – Nigel Aston, Leicester University

“Benefiting from a lifetime’s study, Joseph Bergin brilliantly succeeds in showing us how the French Catholic church was the product of a society that it, in turn, did so much to shape. The result is a remarkable recreation of a diverse religious society to which generations of individuals, clerics and laymen, found themselves committed by shared duty and devotion.” – Mark Greengrass, University of Sheffield

“Joseph Bergin’s outstanding synoptic study combines breadth of coverage and depth of understanding to brilliant effect. He brings out the astonishing scale of the Catholic reform movement in France, while offering an incisive analysis of its inner workings and ambiguities. This now becomes the indispensable book for everyone interested in seventeenth-century French Catholicism, and will also be invaluable to all serious students of early modern French and European history.” – Robin Briggs

“The word definitive is perhaps too often used in reviews, but Joseph Bergin’s new book on the French church in the long seventeenth century certainly qualifies. . . . Throughout the book, Bergin is careful in his judgments, meticulous in his use of a wide variety of evidence, and encyclopedic in his knowledge of the subject. . . . It is unlikely that we shall soon see a better work in any language on the French church in the seventeenth century.”-W. Gregory Monahan, American Historical Review

“Essential reading for anyone who wants to understand seventeenth-century France . . . a masterpiece.”–Michael Hayden, Canadian Journal of History

“Joe Bergin has built his reputation as the world’s leading authority on the early modern French church … He knows the church of the grand siècle from the inside, and in analyzing its structure and workings he has attained the stature … of a great historian. …This should now be the first port of call for anybody wishing to understand why and how this persistently perplexing phenomenon emerged as and when it did.” – William Doyle, French History

“[Bergin’s] new work Church, Society and Religious Change in France, 1580-1730 is a monumental study that only a scholar with his past achievements could contemplate undertaking … A focused and readable survey. There is no question that this book is an important and welcome addition to the field … This book is more than just a survey, it also provides a guide to where further research will transform our understanding of the French Church.” – Eric Nelson, Reviews in History

“The accessibility of a work of such scope makes it worth the the cover price alone. Moreover, in its crucial contributions to historical methodologies which force us to rethink a French “Catholic Reformation” which had fizzled out by 1660, makes this book an essential text for students and academics alike.” – Jenny Hillman, Journal of Early Modern History

“[A] remarkable work.”–Jacques M. Gres-Gayer, Catholic Historical Review