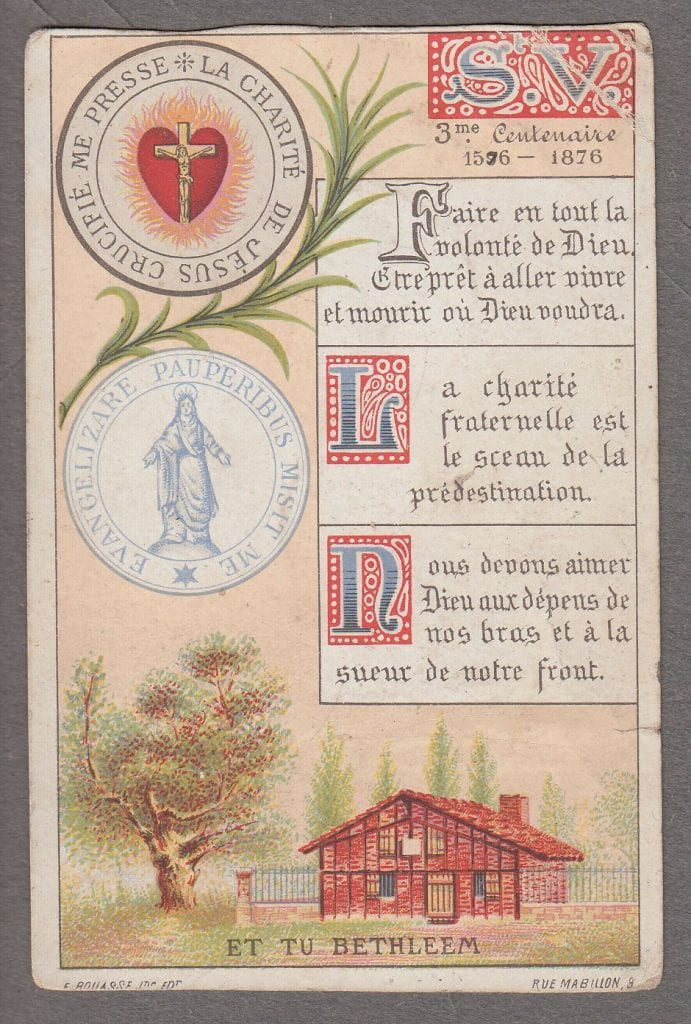

In 1981 the Vincentian family celebrated the 400th anniversary of the birth of Vincent de Paul. The 1581 date resulted from the definitive refutation of the previous date of 1576. The three hundredth anniversary had been celebrated in 1876 as illustrated by this new commemorative card recently purchased for the Vincentiana collections at the Archives and Special Collections of DePaul University.

Holy Card

Writing with a Mission. The correspondence of Vincentian missionaries with Paris and Rome, 1645-1689

In September 2014 I completed my master thesis entitled “Writing with a Mission. The correspondence of Vincentian missionaries with Paris and Rome, 1645-1689”. While collaborating on an online collection of documents regarding the Congregation of the Mission that can be found in the Vatican Archives (especially the Propaganda Fide branch), I became interested in understanding better how the correspondence that I was looking at functioned in practice. Moreover, I was curious to understand how the recipients of the letters, i.e. Vincent de Paul himself and the cardinals of Propaganda Fide in Rome, tried to assess their trustworthiness. The aim of my thesis project therefore was to understand how the practical aspects of correspondence, as well as the dynamic of trust and mistrust influenced the communication between the Vincentian missionaries in Scotland and North Africa with their superiors in Paris and Rome in the seventeenth century.

I discovered that correspondence was the principal way to exchange material and spiritual assistance in return for obedience, information and prayers. Since the missionaries themselves were the main source of information on the mission, to understand whether the requested help was really needed, the superiors and prelates needed to assess the trustworthiness of the writers. The exchange was immediately hampered when trusted lacked. Where this was not the case, major obstacles for effective communication could be the complexity of sending letters over large distances. Both the time it took for a letter to arrive and the danger that it would be lost or intercepted negatively influenced the efficacy of communication. An important way to limit these problems was to rely on a complex network of intermediaries, such as the nuncios, procurators and vicars, who could function as trustworthy substitutes nearer to the recipient of a letter.

When a message would arrive, the effectiveness of correspondence depended on the writing strategies used. The prelates in Rome, the superiors and the Vincentian missionaries all wrote with a mission: they wrote to convince ‘the other side’. Rhetoric in the Vincentian correspondence was always both an expression of the opinion and needs of the missionary, and a (conscious or unconscious) response to what was expected ‘from above’. Writing strategies included keeping silent about certain things that might compromise one’s trustworthiness, and telling those stories that the writer believed might enhance it. Using recognizable commonplaces, quantification of success and a well thought-out sequence of a letter would also contribute to the effectiveness of writing. Although this strategic writing is an important aspect of the correspondence, we should not reduce the missionaries’ aim to merely obtaining things: the Vincentians also wished to simply recount what they retained essential in their experience.

By examining three specific case-studies, I discovered that trustworthiness was an essential, but not self-evident part of communication. It had to be assessed and built up over time. Also the participants in the correspondence did not see it as a finished artifact, but were constantly trying to decide whom to trust. As to the day-to-day practice of letter writing, my research shows that the missionaries consciously chose what to write to whom and what to keep silent about: certain details would enhance the effectiveness of their letters, while other information would only incite mistrust.

In our age of instant communication one easily underestimates the efforts that a seventeenth century missionary had to take to communicate with his superiors from a distance. My findings elucidate how the limitations of correspondence greatly influenced the day-to-day life of the Vincentian missionaries.

Newsnote: “Vincentiana Purchase of the Week” 2/4/2015

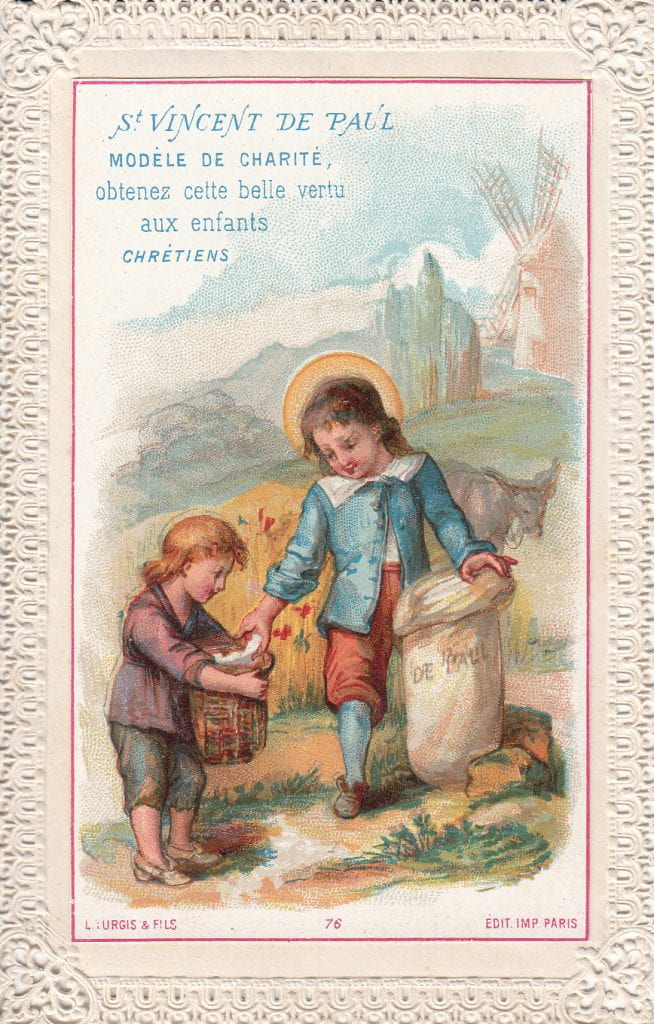

The Vincentiana Collection at Special Collections and Archives of DePaul University recently purchased a late 19th century holy card designed for children, highlighting the sanctity of Saint Vincent de Paul as a child. This depiction is based on the long-standing legend of Vincent helping a beggar as a child. The back of the card has an exhortation to young children to follow the saint’s charitable example.

Newsnote: Vincentiana Purchase of the Week: 1/31/2015

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century there was a flood of French postcards that illustrated cultural and religious fascination with the “bonnes soeurs” who were such a feature of daily French life. During the 19th century French women in large numbers flocked to the new and established religious communities with active apostolates. As tensions with the anti-clerical Third Republic heightened these sisters became symbols in this struggle. The Daughters of Charity with their distinctive “cornette”, were spread across France and were often featured in such postcards. One sub-genre of these postcards include young girls dressed up in sisters habits, and repeating the themes portrayed by the “bonnes soeurs” genre. This black and white postcard is postmarked 1907.

Newsnote: “More World War I damage: Daughters of Charity, Reims, France.”

As the Germans rapidly deployed after the declaration of war in August 1914 their invasion of France included the systematic bombardment of cities like Reims. By the end of the war the city was all but destroyed. This card pictures the Daughters’ orphanage in the city that was completely destroyed by the shelling.

Newsnote: The Daughters of Charity and the outbreak of World War I

With the outbreak of war in August of 1914, the Germans implemented their battle plans and quickly invaded France. The Battle of Longwy took place on August 22-23, 1914 and the fort of Longwy was captured by the Germans. Longwy was the first French fort to be taken by the Germans in the Weltkrieg. Much of the town was destroyed. Including the Asile Margaine run by the Daughters of Charity pictured in the contemporary postcard above. The postcard was recently acquired by the Vincentiana collections in Archives and Special Collections at DePaul University. The postcard bears a military postmark dated May 24, 1915. It was sent home by a German soldier.

Newsnote: Vincentiana Purchase of the Week: The Polish Uprising of 1831

The Vincentiana Collection at Archives and Special Collections of DePaul University this week purchased a rare Polish card dated from the beginning of the 20th century. This card shows a young Polish Daughter of Charity nursing one of the wounded officers from the Battle of Warsaw in September 1831 when Russian forces invaded Poland to crush its rebellion against czarist authority. On 8 September 1831 Warsaw was captured after a valiant defense.

Newsnote: Daughters of Charity nurses in World War I cont’d

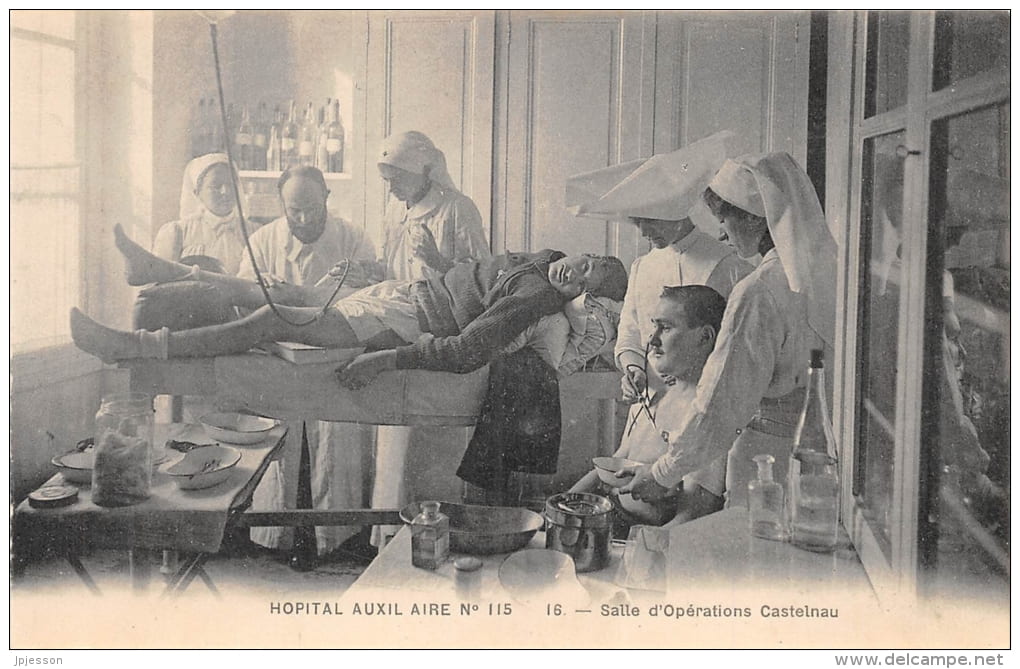

This postcard was part of a recent acquisition by the Vincentiana collection at DePaul University’s Archives and Special Collections. At the separation of Church and State in France at the beginning of the 20th century the Daughters of Charity and other nursing sisters were largely expelled from their hospital work. Ten years later when World War I broke out and the French military hospital system was overwhelmed by a deluge of casualties the sisters were welcomed back to work at newly-formed hopitaux auxiliaires sponsored by women’s division of the French Red Cross. Many of these hospitals were set up in commandeered schools, convents, mansions and other institutions. It is estimated that there were more than 900 French military hospitals set up on an emergency basis during the war. This card pictures a Daughter of Charity working in surgery at Hopital Auxiliaire #115 located in La Raincy outside of Paris.

Newsnote: “Vincentiana Purchase of the Week” World War I Propaganda postcard

“The Germans do not respect the dead, the dying, or ambulances.”

This French postcard produced in 1914, already indicates the tone of bitterness and revulsion for the Germans that was produced by the French propaganda efforts.

This card was recently purchased for the Vincentiana collection at Archives and Special Collections at DePaul University in Chicago.

Newsnote: “Vincentiana Purchase of the Week: Daughters of Charity as W.W. I nurses in France.”

As we enter the great centenary of the World War I anniversaries one of the enduring memories is of epic carnage. The battlefield casualties on all sides of this conflict still stun the mind today. The image of the Daughter of Charity as a battle-field nurse whether in the Crimean War or the American Civil War is an enduring one. However, the greatest involvement of the Daughters of Charity in war nursing was undoubtedly the Great War. Throughout France, and throughout the combatant countries as casualties mounted military hospitals sprang up everywhere hastily thrown together in commandeered schools, orphanages, noble chateaus and other large institutional spaces. In France in particular the sisters who had only a decade before been expelled from French health care at the separation of Church and State were now welcomed back without hesitation. The attached is a 1916 postcard issued by the Societe Francaise de Secours aux Blesses Militaires (the French Red Cross). It had its headquarters at 21, rue Francois 1er (Paris VIII). This card is a scene from the Val de Grace Military Hospital in Paris and captures a haunting moment as a wounded soldier (to the right) is carried by stretcher into the ward, accompanied by the surgeon as the other patients, a lay nurse, and a Daughter of Charity stop for a moment as the scene is captured.

This postcard was recently purchased for the Vincentiana collection at Archives and Special Collections of DePaul University.