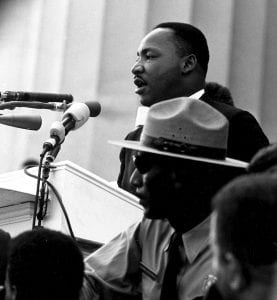

“We have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and God-given rights. The nations of Asia and Africa are moving with jetlike speed toward gaining political independence, but we still creep at horse-and-buggy pace toward gaining a cup of coffee at a lunch counter.”

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail, 1963

I am convinced that the very foundation of the Vincentian Spirit began with, and still demands, a specific approach to understanding reality. It is rooted in the experience of all those on the margins of society deprived of their essential rights to food, education, health care, clothing, and housing, as well as all victims of systemic injustice due to their race, sex, sexual orientation, social class or religion. In this sense, I believe that civil rights and democracy are Vincentian themes, and that in these two “signs of the times” we find a concrete Vincentian call for DePaul as an educational institution.

This week we celebrate the memory and legacy of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. We are also witnessing a national transition of governmental power in the United States that has exposed the fragility of democracy. Governmental stability is necessary for the well-being of people living in poverty or on the margins, as social conflict, pandemics, and natural disasters always disproportionately affect the most vulnerable. Vincent de Paul said that the most vulnerable are “our portion” in life, or our responsibility, our place, our call, and our ultimate vocation. (1)

I believe that the struggle to fully construct our democracy framed Dr. King’s call. He fought for civil rights based on the social contract of democracy—a system that demands we commit to preserve and expand the common good by recognizing and respecting the civil rights of all people as equal. Dr. King fought for the civil rights of Black people and communities in defense of, and to fulfill, the democratic dream that all are recognized and respected as equal in both rights and responsibilities. In the U.S., civil rights are to this day an unsettled issue, as the full incorporation of Black and Brown people into the life of the country is clearly unresolved.

Over the past four years we have seen that democracy is a dynamic—sometimes historic—human-made, socio-political system that is always changing. It therefore never seems to be fully functional. The democratic system demands constant monitoring and oversight to prevent the gradual erosion of its quality. In recent years, as democracy has become a domestic concern for the American people, the U.S. has shifted its priority from defending democracy abroad to scrutinizing itself. Our time of being recognized as the global defender and model of democracy seems to have been lost, and our current crisis is creating questions worldwide. Clearly, strengthening our democratic processes will not only benefit U.S. institutions and citizens, but also the international community.

When leaving the White House, President Barack Obama reminded us “citizenship is the most important position in a democracy.”(2) In the twenty-first century, committed citizens of the world continue to be confronted with the challenges of democracy—whether building it from the ground up, restoring it, preserving it in fragile or failed states, or improving the quality of it in so-called strong democracies like the U.S.

In our society the democratic principles that guarantee peace and prosperity are merged throughout the social, economic, and legal fabric. These principles can be found everywhere in the Constitution, and in the essential democratic underpinnings of human rights, fundamental freedoms, equal rights regardless of gender, freedom of speech, as well as in the elimination of differences of treatment on the basis of race, sex, language, social class, physical condition, sexual orientation, or religion. Dr. King clearly understood that non-racial discrimination is one of these essential principles, without which democracy is simply an unfulfilled dream.

We believe, as Dr. King did, that a fully-fledged democracy, with its legal and ethical basis, is a means to achieve peace, security, economic and social progress, sustainable development, and respect for the human rights of all. I am frightened when I read that more and more young people around the world think there are other means to achieve these goals. They see the failure of the political patriarchal model, the failure and corruption of politicians and political parties, and the severe dismantling of the foundations of our democratic process. For me, it is difficult to comprehend that the civil rights fight Dr. King faced over half-a-century ago, which happened in the context of U.S. democracy, reflects the current outcry for racial justice, and the current context of our democracy. What, then, does this say of our democracy?

DePaul University is a Vincentian institution dedicated to education. We are inspired and sustained by the Vincentian Spirit. The signs of the times are demanding we recognize what has been called “education for democracy” by the United Nations: “a broad concept which can help to inculcate democratic values and principles in a society, encouraging citizens to be informed of their rights and the existing laws and policies designed to protect them, as well as training individuals to become democratic leaders in their societies.”(3) Education for democracy involves an active effort to encourage the full participation of citizens in the different democratic processes. This kind of education demands we attend to the peaceful and non-violent coexistence of diverse societies, including access, equity, social justice, individual and institutional ethical behavior, checks and balances of power as well as individual rights and responsibilities.

Education is also critical in empowering citizens to hold accountable those politicians and political parties that hold positions of power, as well as the institutions designed to create laws and policies that safeguard the rights of all.

Founded in the Vincentian Spirit, DePaul needs to be committed, through its educational practice, to strengthen democratic citizenship and promote effective popular participation. As we celebrate Dr. King and hope for a peaceful and non-violent transition of national power, we must continue our fight for the civil rights of all. The peaceful transition of power is one of the essential principles of global democracy.

We must also not forget that in the U.S. the essential democratic right to vote is yet another unresolved issue. It is evident that Black, Brown, and Indigenous people’s access to free and equal voting opportunities are curtailed through mechanisms such as unjust purging of registered voter lists, lack of access to polling places, and long lines at those polling places that are still operational. We need to resolve this issue, among many others, to restore and protect the meaning of democracy in our nation.

The role of the Black community in the preservation of our democracy cannot be ignored. In recent elections the Black community, again, voted in huge numbers and, in many cases, under unfair conditions. They stood up once more to claim their rights, and in so doing, they helped all Americans regain a vision of the real meaning of democracy. As I remember and honor the life of Dr. King, I want to honor and praise the role of the Black community nationwide, which continues to fight for justice and democracy on so many fronts, and often at high personal cost. It is neither fair nor sustainable to expect Black Americans to continue to bear such a disproportionate burden in the fight for civil rights and upholding democracy.

All citizens are called to defend the principles of our democracy: equality, respect, responsibility, agency, and opportunity for all. But now, in this moment in history, I thank Black leaders like Dr. King for their legacy, the very many activist leaders working for justice today, and all Black Americans who continue the fight to uphold democracy. I thank you for your sacrifices, your contributions, and your critical victories. You are living evidence of the struggle to protect and the resilience to uphold our democracy.

1) Conference 180, Observance of the Rules, 17 May 1658, CCD, 12:4.

2) President Barack Obama, Farewell Address, 10 January 2017. See: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/farewell

3) Guidance Note of the Secretary-General on Democracy, United Nations, 2005. See: Guidance Note on Democracy

Other Bibliography

Campuzano, Guillermo, C.M., Personal Notes, 2018 United Nations meeting on Democracy.

“Conferencias de San Vicente de Paul,” Editorial CEME, XII:4.

King, Dr. Martin Luther, Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail (1963). See: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/02/letter-from-a-birmingham-jail/552461/

Reflection By: Guillermo Campuzano, C.M., Vice President Division of Mission & Ministry

This is a podcast interview with Rev. Craig B. Mousin, founder and former Director of the Midwest Immigrant Rights Center and an Adjunct Faculty member at DePaul University’s College of Law and The Grace School of Applied Diplomacy. Inspired by the Rev. Dr. Silvester S. Beaman’s benediction from the inauguration of President Joseph R. Biden Jr. on January 20, 2021, this podcast urges those seeking to reform immigration law to seek our common humanity. Recognizing the whirlwind of changes in immigration and refugee law from 2017 to the present, the podcast suggests we have to consider what we owe to those who have contributed to the growth of our nation as we reconsider how best to reform our nation’s laws. To listen to the benediction of the Rev. Dr. Silvester S. Beaman, Pastor of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church of Wilmington, Delaware, see: https://bethelwilmington.org

This is a podcast interview with Rev. Craig B. Mousin, founder and former Director of the Midwest Immigrant Rights Center and an Adjunct Faculty member at DePaul University’s College of Law and The Grace School of Applied Diplomacy. Inspired by the Rev. Dr. Silvester S. Beaman’s benediction from the inauguration of President Joseph R. Biden Jr. on January 20, 2021, this podcast urges those seeking to reform immigration law to seek our common humanity. Recognizing the whirlwind of changes in immigration and refugee law from 2017 to the present, the podcast suggests we have to consider what we owe to those who have contributed to the growth of our nation as we reconsider how best to reform our nation’s laws. To listen to the benediction of the Rev. Dr. Silvester S. Beaman, Pastor of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church of Wilmington, Delaware, see: https://bethelwilmington.org