UPCOMING EVENTS

DePaul faculty and staff, please join us for our annual Lunch with Louise honoring the life and legacy of St. Vincent de Paul’s great friend and collaborator, St. Louise de Marillac. This year, we are delighted to have as our featured guests Deans Stephanie Dance-Barnes, Martine Kei Greene-Rogers and Jennifer Mueller, Deans of the College of Science and Health, The Theatre School and the College of Education. We look forward to these university leaders gathering for a spirited dialogue about the challenges and rewards of their jobs as well as sharing how DePaul’s Vincentian mission has helped inform and guide their work at DePaul (and beyond) and their visions for the future. Please join us!

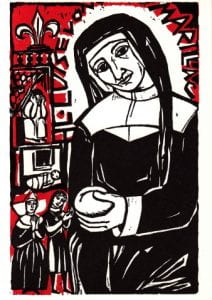

As part of Louise Week, the DePaul community is invited to celebrate the Feast Day of Saint Louise de Marillac with special campus Masses and a shared lunch. Join us in honoring her life of compassion, courage, and commitment to those most in need.

The DePaul community is invited to welcome a new publication by Matthieu Brejon de Lavergnée, Beyond Frontiers: History of the Daughters of Charity. This book is rooted in our Vincentian mission and explores how generations of women shaped education, healthcare, and social justice through lives of faith and service.

Join us in a moment of quiet prayer for DePaul and our President

prior to his testimony before Congress.

Wednesday, May 7th

8:45 AM -9:00 AM

Lincoln Park: St. Louise de Marillac Chapel (Student Center, 1st Floor)

Loop: Miraculous Medal Chapel (DePaul Center, 1st Floor)

Sadly, we have learned of the death of Dr. Hung-Chi Ku, Associate Professor of Mathematical Sciences. He passed away on April 26, at the age of 53. Dr. Hu joined the faculty at DePaul in 2015 and was granted tenure in 2024.

DePaul University Bereavement Notices will now be found here.

Written By: Rachelle Kramer, D.Min., Director, Catholic Campus Ministry

Each morning as I begin a new day, I find myself glancing at my phone and wondering what terrible headlines await on my news app. What denigrating actions have those in power taken today? What vulnerable populations are being targeted? My stomach churns, and I usually decide to postpone my quick perusal of headlines until after my morning routine, to begin the day on a more positive, if not hopeful, note. Moderating my intake of the news cycle has become an essential and necessary step to maintain my emotional and spiritual well-being these days, and I know I am not alone. These are, indeed, incredibly challenging and, dare I say, unprecedented times.

Each morning as I begin a new day, I find myself glancing at my phone and wondering what terrible headlines await on my news app. What denigrating actions have those in power taken today? What vulnerable populations are being targeted? My stomach churns, and I usually decide to postpone my quick perusal of headlines until after my morning routine, to begin the day on a more positive, if not hopeful, note. Moderating my intake of the news cycle has become an essential and necessary step to maintain my emotional and spiritual well-being these days, and I know I am not alone. These are, indeed, incredibly challenging and, dare I say, unprecedented times.

When I notice myself despairing and doomscrolling, I find it helpful to look to other inspiring figures who have also lived through challenging circumstances. One such individual—whom we celebrate at DePaul this week—is Saint Louise de Marillac, companion of Saint Vincent, co-founder of the Daughters of Charity, and trailblazer in her own time. Though living in a different era, Louise’s context in seventeenth-century France was also wrought with complexity and difficulty: wars, extreme poverty, political turmoil, and famine, to name a few. Not only that, Louise suffered tremendously in her life. An “illegitimate” child, Louise never knew her mother, and her father died when she was fifteen. Estranged from her family, she was denied admission to the convent (something she deeply desired), possessed frail health, had a son with special needs, and lost her husband in her early thirties.

Despite these challenges, Louise did not sit on the sidelines. Surrounded by overwhelming suffering and poverty, she got to work. Alongside her companion, Vincent, Louise used her tremendous leadership and organizational capabilities to found a religious community that, in a mere few decades, took charge of hospitals in Paris and the surrounding provinces; provided shelter for abandoned children, creating a whole new method of child care; oversaw ministries to the galley convicts; created a charitable warehouse that saved 193 villages during a period of famine; and started free elementary schools for girls in the Paris archdiocese, a stunning accomplishment during that time. [1]

How in the world did Louise accomplish all of this, given the many challenges and obstacles she must have faced, especially as a woman living in the 1600s? Without question, she was extremely gifted. But there is more to the story. Louise spoke often of her faith in God as her grounding for the work she did. Her spirituality was deeply shaped by the centrality of the Jesus crucified. [2] Having suffered tremendously in her own life, Louise had great compassion for those who experienced suffering, and she felt called to help alleviate it. In forming her community, she, “sought to fix the eyes of her Daughters on the suffering of Christ as the one whom they served in the poor.” [3] Thus, author Louise Sullivan describes Louise as, “a mystic with her feet solidly planted on the ground.” [4] How I love that image! She was a woman who lived in the world, rolled up her sleeves, and got to work, but that work was only possible because she was deeply rooted in something beyond herself—her faith. And it was that faith that provided the wellspring to continue doing the difficult work.

If there is anything we can learn from Louise during our present-day challenges, I believe it is this: we, too, can be “mystics with our feet solidly planted on the ground.” While we at DePaul do not all ascribe to Louise’s Christian faith, I do believe that we, too, need a well to draw from that is bigger than ourselves so that we can both persevere and take the actions needed during these troubling times. For some, that well is called God. For others, it is named in a sense of spirituality, or the interconnectedness of all humanity, or the inner conviction that living a life committed to justice, solidarity, and selflessness is worth living. Whatever that well is for you, hold fast to that. Be a mystic by taking time to pray, reflect, meditate, or sit in silence (lose the phone!)—whatever you need to tap into that Reality. We need this reservoir to get us through.

May the example of Louise inspire us to stay grounded in something beyond ourselves, to act, and to move forward in hope.

Questions for Reflection:

Reflection by: Rachelle Kramer, D.Min., Director, Catholic Campus Ministry

[1] Louise Sullivan, “Louise de Marillac: A Spiritual Portrait” in Vincent de Paul and Louise de Marillac: Rules, Conferences, and Writing, ed. Frances Ryan and John E. Rybolt (New York: Paulist Press, 1995), 49–57.

[2] Sullivan, “Louise de Marillac,” 57–58.

[3] Ibid., 58.

[4] Ibid., 60.

This year Vincentian Service Day is Saturday, May 3rd and registration is available on the VSD website. We have over 25 community partners ready to welcome you!

You can register as an individual or as a group for a service site. If you would like to participate in VSD as a group, please check out the Group Registration FAQs on the website for more information about the this registration process. You can also view this video, which provides a step-by-step guide to group registration. You must log in with your DePaul credentials to view the video.

We are excited about the many opportunities to engage in service and hope you will participate! If you have any questions, please email serviceday@depaul.edu and a member of the VSD Team will get back to you. We hope you will participate in this longstanding DePaul tradition!

DePaul faculty and staff, please join us for our annual Lunch with Louise honoring the life and legacy of St. Vincent de Paul’s great friend and collaborator, St. Louise de Marillac. This year, we are delighted to have as our featured guests Deans Stephanie Dance-Barnes, Martine Kei Greene-Rogers and Jennifer Mueller, Deans of the College of Science and Health, The Theatre School and the College of Education. We look forward to these university leaders gathering for a spirited dialogue about the challenges and rewards of their jobs as well as sharing how DePaul’s Vincentian mission has helped inform and guide their work at DePaul (and beyond) and their visions for the future. Please join us!

Written By: Katie Brick, Executive Assistant, Division of Mission & Ministry

During the Great Recession of 2007–2009, I recall how DePaul adjunct chaplain Maureen Dolan expressed great hope that people would turn toward one another in mutual care, because they had to, given the difficulties being faced. During a scary time, she saw opportunity for people with means to simplify their lives and consumerist habits, share living spaces, and pitch in to support one another in a way that often only happens when we’re forced to do it.

I’m not sure how much has changed, but here we are again facing economic and social volatility. Amid anxiety, I sometimes hear Maureen’s voice in my head, may she rest in peace, asking: What can grow right now? What community can be developed because it has to be developed? How can you take your uncertainty and the pain that is happening in society and humbly contribute to something positive—something that may lead you and others to a much more satisfying way of being?

Maureen’s hopes and questions seem to reflect those of Saint Vincent de Paul. Speaking of loss, he wrote, “If the world takes something from us on the one hand, God will give us something on the other.” [1]

What can we gain from uncertainty, apparent loss, and sometimes forced simplicity? What divine gift might come from this?

With the recent death of Pope Francis, I have reflected on his kinship with Vincent and our university’s Vincentian forebearers in the Vincentian charism. In a 2017 address on the Feast Day of Vincent de Paul, Pope Francis said of Vincent, “He prompts us to live in fraternal communion among ourselves and to go forth courageously in mission to the world. He calls us to free ourselves from complicated language, self-absorbed rhetoric, and attachment to material forms of security. These may seem satisfactory in the short term but they do not grant God’s peace; indeed, they are frequently obstacles to mission.”

I believe that Pope Francis, who admired Vincent de Paul, shared many qualities with him. These included deep faith, great care for the poor and vulnerable, a desire for reform within the Catholic Church, a loving heart, and a simple lifestyle admired by many. Most of all, he had a vision for what the world should be like, coupled with gifts to inspire and exhort people to action. Just hours before he died, Pope Francis asked world leaders to band together, as Maureen asked people to band together, and as Vincent and Louise established communities of service to bring people together. He said, “I appeal to all those in positions of political responsibility in our world not to yield to the logic of fear which only leads to isolation from others, but rather to use the resources available to help the needy, to fight hunger and to encourage initiatives that promote development. These are the ‘weapons’ of peace: weapons that build the future, instead of sowing seeds of death!” [2]

It remains to be seen how our brand new Pope, Leo XIV, will guide the Church and communicate to the world about current times. In his first address after being announced, he called on the Church of Rome to “seek together how to be a missionary Church, a Church that builds bridges, dialogue, always open to welcome…all those who need our presence,” and said he wants the Church to be one that “…always seeks peace, always seeks charity, always strives to be close especially to those who suffer.” These seem to be words of compassion, with an eye to serving those in need, and I am glad of it.

Our mission calls us to mutual care and active concern. People you know, perhaps colleagues or your version of Maureen Dolan—and key Vincentian figures like Vincent, Louise de Marillac, and Frédéric Ozanam, or the recently departed Pope Francis or our new Pope, Leo XIV, ——provide models and heart in a time when we need a new way of being a human community. I am inspired by them when I slow down enough to allow myself to be. As I can all too quickly return to fear and isolation, I depend on them and others to pull me out of self-focus and into having a broader perspective. In turn, I am called to do that for others. It’s an interdependence for which I am extremely grateful, and I am reminded to walk a path that can get obscured in the chaos of modern life, but which is supremely important.

Reflection Questions

Reflection by: Katie Brick, Executive Assistant, Division of Mission & Ministry

[1] Letter 2752, “To Monsieur Desbordes, Counselor in the Parlement,” December 21, 1658, CCD, 7:424. Available online at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentian_ebooks/32/.

[2] Francis, “Urbi et Orbi,” April 20, 2025. Available online at: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/messages/urbi/documents/20250420-urbi-et-orbi-pasqua.html.

Reflection by: Mark Laboe, Interim Vice President, Mission and Ministry

A very influential and helpful idea on my personal spiritual journey emerged for me decades ago when I read This Blessed Mess: Finding Hope Amidst Life’s Chaos by Patricia Livingston. The simple yet profound main idea that captured my attention and that I internalized was this: just as God created life, love, and beauty out of darkness and chaos (see Genesis), so must we be agents of the ongoing creative process in our own lives, during which we often face moments of chaos. Furthermore, there is a creative energy that is present within the chaos of our lives that can ultimately become transformative and life-giving. Grasping this idea conceptually is one thing, but living it is another.

Fortunately, life inevitably provides a lot of practice by bringing us situations that feel like chaos again and again over the course of a lifetime. This might take the form of heartbreaking and tragic losses, illness and injury, or seemingly impossible situations in which the whole world seems to be against us. We may also have to deal with the painful aftermath of harmful human decisions and actions, whether our own or those of others (such as war and violence, greed, or ego-driven and self-centered behaviors). Whatever form it takes, the word “mess” is an unfortunately adequate description for what we often face in our lives. How could this “mess” possibly be “blessed”?

One piece of adult wisdom that helps us get through such moments comes in remembering simply that “this too shall pass.” I have heard it suggested that the difference between the child and the adult is that that adult knows the moment will pass. A child or adolescent is without the life experience to know that a painful life situation will eventually give way. Christian theology holds the profound understanding of the paschal mystery, modeled in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, to understand that there is hope and the potential for new life and redemption on the other side of death and suffering.

In fact, each “blessed mess” offers us an opportunity to clarify and define who we are and who we will become moving forward from that difficult moment. It is an opportunity to create and re-create our lives, grounded in the values and actions we know or believe to be good, true, and beautiful, and for the betterment of humanity. Victor Frankl, the famous Holocaust survivor, is known to have said that “everything can be taken from a (person) but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” [1] Though I may first complain and cry in the face of chaos, sometimes I can also then laugh out loud when things start piling up on me and I realize that I am more… and life is more… than what I am experiencing in that moment. I am encouraged when I consider the freedom that I have to choose how I will face it.

Moments of “chaos” lead me repeatedly to the question: What anchors and guides me now and ultimately? What values and commitments do I want my life to reflect, and do I want to choose to live into in this moment? Which are most consistent with who I know myself to be and believe I was created by God to become? And how can we answer these questions in applying them to ourselves as a community?

Institutions and communities go through similar moments. Yet, making a shared commitment or “attitude adjustment” as a collective is quite a bit more complicated than just deciding to do so for oneself. It can be work, and it can require patience, empathy, generosity, love, and courage to get all on the same wavelength. Yet, having a shared mission to draw on can help a community like ours at DePaul. As we move through difficult and uncertain moments, our periods of chaos can become opportunities for clarification, for remembering and re-committing to each other, and for carefully discerning the values and sense of vocation that anchor and guide us.

I have often heard two related African proverbs quoted that emphasize the communal nature of the human person. They serve as important reminders about how we may best move through communal moments of chaos. One states that “no one goes to heaven alone,” and another is, “If you want to go fast, go alone, and if you want to go far, go together.” In a society and world that is so often individualistic or that struggles to bridge divides, such a communal mindset is countercultural. However, at DePaul, we often point to an understanding that we are a “community gathered together for the sake of the mission.” This is a modern take on the initials C.M. for Congregation of the Mission, the apostolic community we may better know as the Vincentians, established by Vincent de Paul. Our mission, therefore, offers us the encouragement and the charge to be countercultural in working and caring for the good of the whole, rather than simply defending our own individual positions or being satisfied simply with “going it alone.”

To move through moments of chaos in our lives, then, we benefit from seeing them as opportunities to anchor ourselves more deeply in what is most important and most true to who we are, and to do so together with others. The moment will pass, and we will endure. The question that remains throughout it all is who we will become in the process. Such moments reveal the ultimate gift and test of our human freedom, our identity, and our mission.

Reflection by: Mark Laboe, Interim Vice President, Mission and Ministry

[1 ]Dave Roos, “Viktor Frankl’s ‘Search for Meaning’ in 5 Enduring Quotes,” June 7, 2024, howstuffworks.com, at: https://history.howstuffworks.com/historical-figures/viktor-frankl.htm.

With this reflection, we send Easter greetings to all the people connected to DePaul University, people of all religious traditions and none. We come together out of our shared need for meaning, peace, healing, and a space and time of rest for our restless hearts. I invite all of you to enter that place with us.

In the Christian world, Good Friday is full of a cry of suffering, pain, and abandonment: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46). This is the cry of the anguish and desperation of the Christ on the cross.

“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” is the painful cry of too many today. When working at the United Nations, I became aware that this cry of anguish and pain of life in all its forms is caused by many different environmental and social realities: missing species, shrinking habitats, collapsed fisheries, bitter seas, soil erosion, plastic apocalypse, the mass-spreading of diseases, rising sea levels, environmental refugees, receding forests, melting glaciers, rising greenhouse gases, massive migrations of species trying to survive, more intense storms, endless winters, growing deserts, arctic meltdown, climate volatility, economic chaos, scandalous inequality, the spread of mental illnesses, inability or lack of interest in outlining an ethic for human-technological interaction, the festering wounds of racism and classism, misogyny and racial, gender, religious, economic hegemony, human trafficking and slavery, economic injustice, inequality and discrimination against minorities of various identities, violence, war, and toxic polarizing politics… and the list goes on.[1]

In this context, it seems appropriate to ask, Where is God? The feelings of abandonment and despair are not far from many of our minds and hearts, even if some may feel uncomfortable thinking this way. When Vincent heard this cry of the most abandoned, he dared to listen. He began a movement of resilient hope, nonviolence, and peace, transforming solidarity. He decided to follow the wisdom and direction of life, not death.

In the Vincentian movement, we are committed to telling people living in suffering and desperation that they are not alone and have not been abandoned and that God is with them. Often the only sign of God that feeds their hope is in the hands, the solidarity, and the compassion of a growing number of people of goodwill who continue to join the human march toward life, hope, reliance, justice, and peace.

We are not exempt from the consequences of the chaos of our interconnected, globalized world. Among us in our neighborhoods and our many communities of belonging here at DePaul University, if we are attentive, we can hear in the cry of vulnerable life a call for help too.

Concretely, during these challenging days, when in conversations and decision-making processes related to Designing DePaul and our projected budget gap, we must always be attentive to hear the cries for help of the most vulnerable members of our community. In this way, meaning, equity, and the sense of belonging will prevail, and we will continue to be rooted in the Vincentian spirit.

The Easter season is full again with good news: The Lord is risen, Alleluia! (Matthew 28:5–7).

According to the Christian scriptures, “very early in the morning, on the first day of the week, [women] went to the tomb when the sun had risen” (Mark 16:2). Amid the darkness, they set out on the road giving company to each other.

Because it is not yet dawn for so many peoples, these women of the morning are calling us to overcome all fear and to set our feet on the road together to witness and actively be part of the triumph of life over death. At every dawn in each corner of the world, millions of humans set out on the road and are the door to each grave; they are witnesses of life, light, and hope.

In the Christian tradition, when we are amid our pain, trials, and anguish, asking why God has forsaken us, God surprises us with a new presence, many times in little signs that we need to identify and translate. The resurrection of the Lord is not a magical experience but a lived reality in the communities that dare to make the call for mutual help and care central to their common survival.

In the Christian paschal mystery, the darkest part of the night is often shortly before the dawn. “The joy comes in the morning” (Ps. 30:5). The joyful proclamation of the Resurrection on Easter Sunday assures us that the last word lies not with violence, injustice, and inhumanity but with God’s purpose of love, justice, and hope. This purpose runs like a thread throughout history and will find its ultimate fulfillment in the coming fullness of the Kin-dom, the common eschatological place where all cultures and religions and all species in our common home are going.

As a Vincentian, I am excited to be alive this Easter. I see a movement in the Catholic Church that is once again looking for a profound transformation. This Easter season invites us to live and generate a culture of renewal in the heart of the Church as we follow Jesus in our total commitment to the protection, care, and survival of life.

Pope Francis is inviting the Church to embrace the gospel of nonviolence as a concrete expression of our commitment to life in the context of the Easter celebrations of this year: “Living, speaking, and acting without violence is not giving up, it is not losing or giving up anything, but aspiring to everything.” May we spread this culture of nonviolence far and wide. May we all join the world in praying for such a nonviolent culture. May we move forward with great gratitude for this word calling us to the fullness of the nonviolent life “aspiring to everything.” (You can see the original press release here.)

Pope Francis knows that the gospel of nonviolence has not always characterized Christianity. Christians have often been a significant obstacle to God. As a part of our commitment to live as resurrected people, we need to ask for forgiveness for the “holy wars,” the inquisition, for blessing guns and bombs, for attempting to justify and participating in the torture and enslavement of human beings, for holding signs that say that God hates people of various minorities, for starting violent apocalyptic militias, for blowing up abortion clinics, for turning a blind eye to poverty and exclusion, and for the sexual abuse of children by priests and religious. These things, and many others, are not the Christianity of Jesus Christ who publicly forgave his killers. They are a Christianity that has become unrecognizably ill and that does not reflect the paschal mystery in which violence, abuse, exclusion, injustice, and death are defeated.

Reflection by: Fr. Memo Campuzano, C.M., Vice President of Mission and Ministry

[1] In this list I am using the language I read and heard in United Nations documents, meetings, and conferences.

By

Emily LaHood-Olsen

Vincentian Service & Formation Team

Division of Mission & Ministry

When my daughter gets older and asks me to recount life in a time of COVID-19, I will tell her about the day last week when we played in the courtyard in front of our building. Every time a neighbor walked outside, she would pick a dandelion, run toward them saying, “Hi!” and try to hand them the flower. All the while, I gently held her back. I will share my fear that social distancing would severely impact her development—that it would teach her to fear the close contact of others or make her too dependent on screens for social interaction, that it might create a stunted understanding of community.

I will share with her the frustration and anger that bubbled up in the face of social inequity, the disregard of science and human life, the apparent inability to mobilize to get safety equipment to grocery store workers, public transit drivers, medical professionals, and hospital janitorial staff.

I will share with her the frustration and anger that bubbled up in the face of social inequity, the disregard of science and human life, the apparent inability to mobilize to get safety equipment to grocery store workers, public transit drivers, medical professionals, and hospital janitorial staff.

I will tell her that the word COVID, in a word, was resilience.

When all this began, I prepared myself for the trauma of these times. I expected to be inundated with news of COVID-related tragedy and prepared my spirit accordingly. What I did not expect was to grieve a perfectly normal, non-COVID death. Five weeks into quarantine, my father-in-law died from undetected bone cancer.

Since then, my husband and I have been navigating a complex, confusing state of mourning. We cannot fly to Washington to be with family or ritualize his passing. We cannot gather in person with our community to receive hugs or share memories. We cannot ask friends to babysit our little one so that we can take some time to simply be sad with one another. The lakefront, our church, and the coffee shop that brings us comfort down the street are all closed; and, we are living each day within the walls that carry our grief.

The plans we made to face the unknown at the onset of shelter-in-place are now completely out the window. We are learning a new kind of resilience.

This experience has prompted me to think about Louise and her journey. Louise experienced an incredible amount of grief and disappointment throughout her life. She was rejected by her family, deprived of her education when her father died, and denied her dream to become a Dominican nun. Although she felt marriage was not her calling, she entered into an arranged marriage. Her son had developmental issues that she did not have the resources to understand. Her husband grew incredibly ill, and she cared for him through his death.

Nothing in Louise’s early life went the way she planned; and yet, she remained resilient. This resilience equipped her to shatter the barriers that blocked her path.

Louise saw the needs of the world and responded in radically creative ways. In a society that offered only two options for women—marriage or cloistered religious life—Louise forged a new way. The Daughters of Charity were the first religious women to be out in the world, unconfined by convent walls, serving people on the streets. Oral history tells us that Louise “misplaced” the letter from the Vatican mandating that the Daughters should be a cloistered order.

Louise saw the needs of the world and responded in radically creative ways. In a society that offered only two options for women—marriage or cloistered religious life—Louise forged a new way. The Daughters of Charity were the first religious women to be out in the world, unconfined by convent walls, serving people on the streets. Oral history tells us that Louise “misplaced” the letter from the Vatican mandating that the Daughters should be a cloistered order.

Seeing that the Vincentian family understood the reality of those who were poor and marginalized, Louise bucked tradition and had the Daughters make their vows to the Vincentians, not to the Vatican. To this day, instead of making lifelong vows Daughters renew theirs annually.

In the face of a broken class system, Louise welcomed women from peasant families into her home, taught them how to read, and recognized the gifts that they could offer the community. This was unheard of for a woman of social class and means.

Louise’s faith and creativity made her open to new possibilities.

We are all learning new ways to foster resilience. Whether coping with feelings of isolation or weathering economic hardship or grieving the illness or death of a loved one, we’re forced to remind ourselves day after day that we can do hard things. And within these hard things, there is an opportunity to vision a world that has never existed before.

When this time of pandemic is over, our call as Vincentians will not be to return to life as usual. It will be to build the world we dream is possible.

A world that values people over profits and sees healthcare as an essential human right.

A world committed to healing our ailing planet instead of returning to fossil fuel dependence.

A world where neighbors delight in one another’s presence and know each other’s names.

In the midst of the unknown, we all have an opportunity to tap into our inner Louise, to build a sense of resilient creativity. Let us dream of the way the world could be, and give those dreams life in the face of hard times.