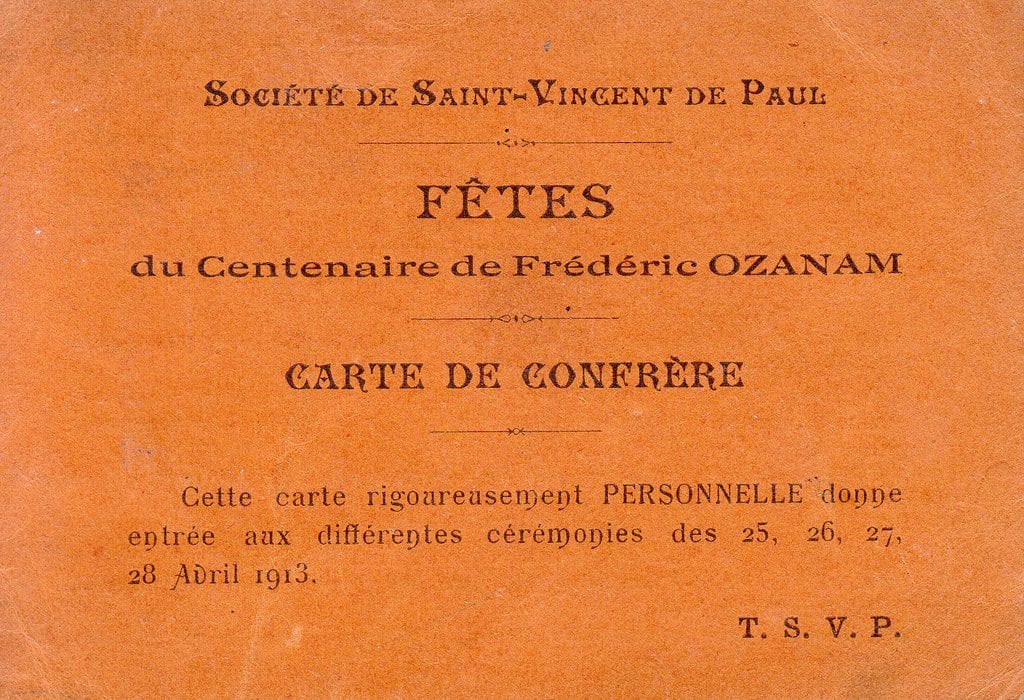

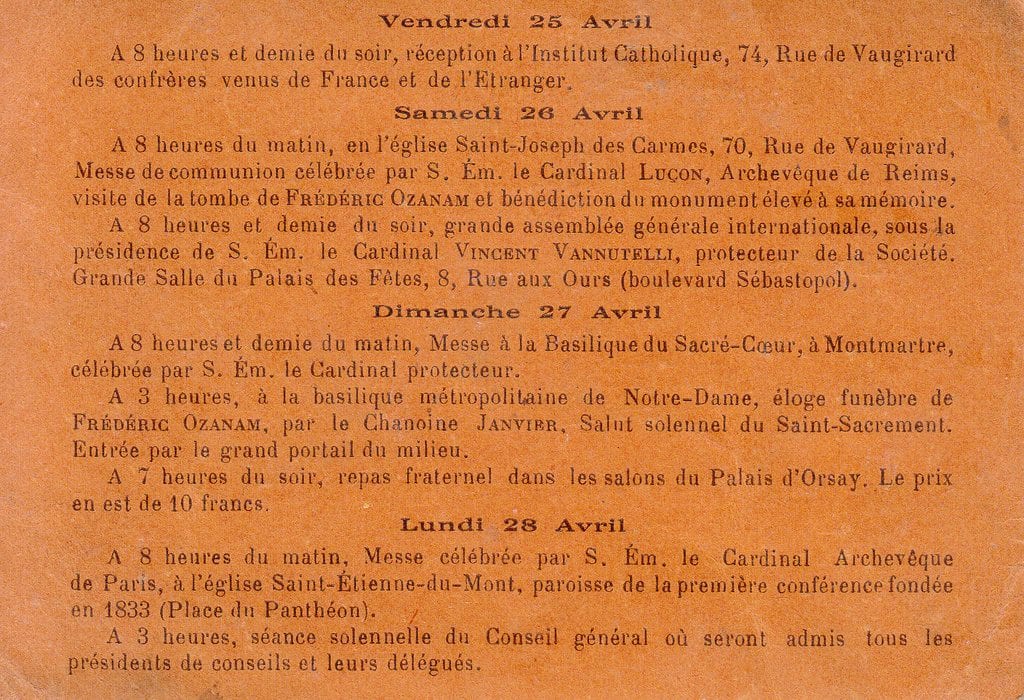

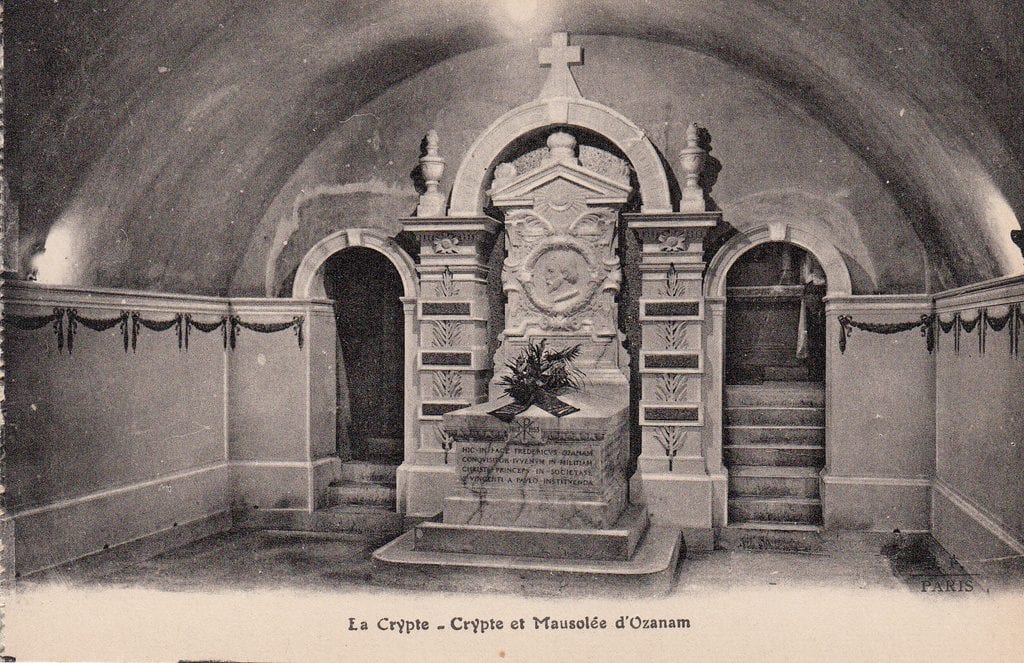

The terms “systemic thinking” and “systemic change” were not used in Frederic Ozanam’s day, but aspects of his perspective and some of his methods for combating poverty fall under those categories. Peter Senge’s framework for systemic thinking is applied to Ozanam’s work. This article also describes how Ozanam’s efforts correspond to strategies identified in the Vincentian publication Seeds of Hope: Stories of Systemic Change. In Ozanam’s view, poor persons should be treated with dignity, and he had a practical understanding of how poverty could be alleviated. The organizational model and processes of the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul are explained. It was important to Ozanam to create a flexible worldwide network that could use experience to form sustainable solutions to poverty. There was reciprocity to the Society’s charity. Poor persons were empowered, and the Society’s members were transformed in their attitudes and grew in holiness through service and theological reflection. To bring about a fairer and more charitable world, both individuals and society had to be transformed.

“Frederic Ozanam: Systemic Thinking, and Systemic Change” is an article published in the Vincentian Heritage Journal, Volume 32, Issue 1, Article 4 (2014) and is available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol32/iss1/4