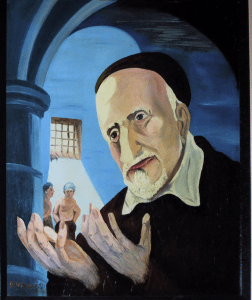

New York University students, faculty, and clergy gather at the Kimmel Center on the NYU campus to discuss the discovery of surveillance by the New York Police Department on Muslim communities.

New York University students, faculty, and clergy gather at the Kimmel Center on the NYU campus to discuss the discovery of surveillance by the New York Police Department on Muslim communities.

By Aaron Shapiro | November 13, 2012

Many American universities—both religious and secular—have recently launched efforts to accommodate and encourage religious diversity on their campuses. Universities are fosteringthis diversity and strengthening interfaith respect and cooperation to better serve their students and to counter rising incidences of xenophobia and other prejudices. Colleges are taking particularly active steps to welcome Muslim students, who too often face discrimination and prejudice because of their faith.

The number of Muslim students enrolled at Catholic universities has reportedly doubled over the past decade. In fact, according to the Higher Education Research Institute, the percentage of Muslim students at Catholic universities is higher than at “the average four-year institution in the United States.” Many may assume this influx of the religious “other” might generate tension, and that has indeed been the case on some campuses. But while much attention has been paid to instances of conflict and discord, the firsthand experience of many students suggests that, theological differences aside, having a religious identity of any kind can serve as a point of commonality for many students.

Muslims thrive on interfaith campuses

Many Muslim students are in fact choosing to enroll at Catholic universities precisely because of the religious—albeit non-Muslim—student body. Maha Haroon, a Muslim student at Jesuit Creighton University, said, “I like the fact that there’s faith, even if it’s not my faith, and I feel my faith is respected.”

Similarly, many Muslim students express a sense of belonging at these institutions because they are surrounded by other people of faith. Beyond merely co-existing, Muslim students are finding their fellow classmates to be welcoming faith partners. Mai Alhamad, a Muslim student at the University of Dayton, told The New York Times that he finds comfort in these efforts, saying, “Here, people are more religious, even if they’re not Muslim, and I am comfortable with that.”

So, too, is Dana Jabri, a sophomore at the Catholic DePaul University. Unsettled by the recent killing of four Americans, including Ambassador Chris Stevens, in Libya and the violent demonstrations that subsequently spread across the Middle East, Jabri felt compelled to organize her fellow students to respond to the violence.

“We needed to come together and just share a moment of silence,” Jabri said in a recent interview with the Center for American Progress.

She worked quickly to organize a vigil on campus protesting violence around the world. About 40 students and faculty from a variety of faiths attended the event and Jewish, Christian, and Muslim chaplains shared their thoughts and prayers. As she recalled the vigil, Jabri said that it felt like a meaningful achievement to simply be able “to stand shoulder to shoulder in a circle, recognizing that it is important for all of us to come together, no matter our faith backgrounds, against this violence.”

As a Muslim and a religious minority at a Catholic university, Jabri has thrived on campus. Jabri is one of DePaul’s seven interfaith scholars—a group of student leaders, each hailing from a different religious tradition, who work with each other and their respective religious communities to cultivate a robust interfaith community on campus.

This kind of engagement extends beyond Roman Catholic universities. Many Muslim students, for instance, are finding common ground with their classmates at Brigham Young University’s Salt Lake City, Utah campus which is “supported, and guided by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints” and where 98.5 percent of all students are Mormon. The values promoted in the BYU Honor Code include “shun[ing] alcohol, illicit drugs and pre-marital sex,” and areimportant in the Muslim faith. These and other similarities have created a sense of solidarity among Muslim and Mormon students, leading Muslim student Sameer Ahmad to conclude that “[Mormons and Muslims] emphasize the same teachings, the same set of beliefs, even though the way of participating [is different].”

In the course of living and studying together, many students at BYU have discovered that their faiths can bring them together instead of pushing them apart. Andrew Moulton, a Mormon who lives with a Muslim classmate, told the Deseret News that, “I didn’t know that our cultures were so similar.”

But it is not just friendships or a sense of belonging that is prompting this increase in Muslim students at non-Muslim religious universities. Brigham Young University is taking concrete steps to create a more welcoming environment for its Muslim students. Each Friday, for example, the university sets aside a room in the student center where its Muslim students can gather for prayers.

Other religiously affiliated universities are making similar efforts to ease Muslim students’ adjustment to campus life. In early October of this year, Gannon University, a Catholic university in Erie, Pennsylvania, completed construction of a new “Interfaith Prayer Space,” where students from all faiths are able to pray and study in accordance with their religious traditions. In another expression of the school’s commitment to engage its Muslim population and improve its interfaith activities, during the ceremony dedicating the new space, Rev. Michael Kesicki read from the Bible and a Muslim student read a passage from the Qur’an.

Many other universities are developing programs and policies that are designed to make Muslim students feel more welcome, as well:

- Benedictine University in Lisle, Illinois, where 15 percent of the students identify as Muslim, compared to the average 1.3 percent of students at four-year colleges,established dedicated prayer rooms for Muslim students and launched an “Interreligious Dialogue” program, inviting students from different faiths to discuss a wide range of issues, including anti-Muslim sentiment.

- Georgetown University, in addition to reserving space for daily Muslim prayers, employs Imam Yahya Hendi as a university chaplain in its multifaith Campus Ministry in Washington, D.C.

- American University, which is affiliated with the Methodist Church, actively engages Muslim students through its Kay Spiritual Life Center in the nation’s capital and its Muslim Chaplain Imad-ad-Dean Ahmad.

By taking actions that express concern and sensitivity toward students of all faith traditions, these universities have demonstrated a commitment to bridging the river of religious differences and countering the idea that religious diversity inevitably breeds discord. Other universities that have yet to take action ought to note the successes of these programs at both religious and secular institutions—most notably the one fostered by non-religiously affiliated New York University.

New York University as a secular model for interfaith community-building

Well-known interfaith activist Eboo Patel once noted that interfaith work on religious campuses is often successful because it “fits in the category of faith language and fits in the category of diversity. It’s just a different dimension.” As shown above, creating interfaith communities on religiously affiliated campuses is a fairly straightforward task since many religions have similar views on lifestyle choices, even if the specific tenets of each faith are very different.

Building interfaith communities at secular universities among a religiously diverse student body therefore poses a distinct challenge. Nonetheless, several secular universities are leading efforts to create inclusive spiritual environments for students from different religious backgrounds because they see the religious diversity of their student body as a resource upon which to build.

New York University in particular stands out as a model for vibrant interfaith community building. Barely more than a year ago, NYU opened the Global Center for Academic and Spiritual Life on its campus in lower Manhattan. This new building houses the Islamic Center and Catholic Center at NYU, and hosts Friday evening prayers for the Jewish campus community each week.

In 2011 a student club at NYU—Bridges: Muslim-Jewish Interfaith Dialogue—coordinated an event where Jewish students attended the Friday afternoon service at the Islamic Center, while Muslim students attended the Friday evening Shabbat service later that night. Naturally, the group titled the program the “Jum’ah/Shabbat Experience.” This event demonstrated that multifaith initiatives need not ignore religious differences and can instead embrace religious difference as an opportunity to learn more and broaden horizons.

While the Spiritual Life Center at NYU hosts many significant interfaith events, some of the most innovative and inspiring initiatives take place beyond its walls. In March 2012, in connection with President Barack Obama’s Interfaith and Community Service Campus Challenge, the White House highlighted a joint effort—led in part by the Bridges student group—in which both Muslim and Jewish students from NYU volunteered to help repair homes damaged by a tornado in Alabama. Chelsea Garbell, president of Bridges and a senior at NYU,explained the larger collaborative vision of the effort: “If we [Muslims and Jews] can learn from one another and develop an understanding of our similarities and differences, we can stand together as human beings in an effort to better the world around us.” By cultivating genuine interfaith relationships and taking interfaith discussions beyond the safety of the university grounds, students can both develop themselves and extend interfaith reach and significance to the greater community.

But NYU’s interfaith efforts also go beyond extracurricular activities: Administrators are bringing interfaith discussions into the classroom. Over the past year NYU chaplains Imam Khalid Latif and Rabbi Yehuda Sarna have been teaching a joint course, titled “Interfaith Dialogue, Leadership & Public Service: Traditions of Engagement in the U.S. & Beyond.” Students from diverse religious backgrounds have taken the course, where they learn how to build a better world while forming an authentic interfaith community—all in the safety of a college classroom. This means that they have a chance to interact with those of different faiths in a calm, intellectual setting, where they can truly air their opinions and hear from those who think differently, deepening their sense of other religions as well as their friendship as classmates.

Through these efforts and others, NYU is actively cultivating a community where students from distinct faith traditions can engage as classmates and fellow human beings, and where they can come away enriched instead of divided.

The result: Standing together through a crisis

The Associated Press reported in February that the New York Police Department was keeping Muslim students at NYU under surveillance because of their religious affiliation. Muslim students were outraged and organized a rally against this invasion of privacy. Atheists, Christians, Sikhs, Jews, Hindus, and others stood together with their Muslim classmates at the rally, bringing to life the slogan “NYUnited,” which was emblazoned across the t-shirts worn by many rally attendees.

Among the many speakers who stood before the podium at the foot of NYU’s Grand Staircase was Ariel Ennis, a Jewish student. Ennis shaped much of his speech around a quote fromAbraham Joshua Heschel, a prominent Rabbi during the Civil Rights Movement. Ennis said:

We may disagree about the ways of achieving fear and trembling, but the fear and trembling are the same. The demands are different, but the conscience is the same, and so is arrogance, iniquity. The proclamations are different, the callousness is the same, and so is the challenge we face in many moments of spiritual agony.

Ennis was able to speak as a Jew to a largely Muslim audience that day primarily because of his efforts and the efforts of the larger NYU community to develop a strong interfaith community—one that promotes solidarity despite difference and fosters unity without uniformity. As he reflected on the “most profound impact” that interfaith community development had for him, Ennis said that “[It] is not that we have necessarily solved world crises, but we have formed real friendships, deep and meaningful friendships, with many members of the [Muslim] community.”

Conclusion

The lesson of moments such as this seems clear: Building community takes time, effort, and the firm belief that our shared core values are more essential than our differences. Such efforts are central to our well being as a democratic nation. In the face of terrorist threats from Al-Qaeda and other groups of religious extremists, we must stand together as a nation of many cultures and faiths, instead of splintering apart from intolerance and hate.

Anti-Muslim prejudice, hate rhetoric, and bigoted actions divide and weaken our country. According to the FBI, hate crimes against Muslim Americans increased by 50 percent in 2010—the highest number since 2001. Muslim Americans seeking to worship according to their faith have seen their mosques defaced, burned, and destroyed.

But if we choose—much like Ariel Ennis and others at NYU and at other institutions around the country have chosen—to stand together, cultivating our commonalities while celebrating our differences, then we can stem the tide of religious intolerance. Together we can continue to uphold the American values of freedom and tolerance for all.

Aaron Shapiro is an intern with the Faith and Progressive Policy Initiative at the Center for American Progress. For more on this initiative, please see its project page.

To Visit the Link on the Center For American Progress website:

Universities Welcome Muslim Students Through Interfaith Efforts

Mission and Ministry’s Abdul-Malik Ryan published an op-ed in Visible Magazine talking about his work as a Muslim Chaplin here at DePaul. Below is an excerpt from the article:

Mission and Ministry’s Abdul-Malik Ryan published an op-ed in Visible Magazine talking about his work as a Muslim Chaplin here at DePaul. Below is an excerpt from the article: