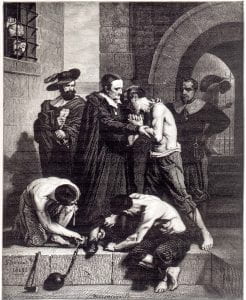

In the stories that we often hear about Vincent de Paul, many touch upon his “love of the poor.” For Vincent, this meant recognizing the sacred dignity of persons so often abandoned and marginalized in seventeenth-century French society. He understood that God was present in and through them. His work began with those in rural communities who did not have the resources, services, or opportunities necessary to survive and thrive physically and spiritually. Eventually, his work also included those he encountered in urban Paris, such as abandoned children and the sick, as well as the galley slaves that he encountered through his connection to Monsieur de Gondi, a French naval officer.

Vincent de Paul’s sense of mission resonates with what we now know as Catholic Social Thought (CST) or Catholic Social Teaching, a body of thinking and practice that has emerged over the last 125 years in the Catholic Church. In both Vincent’s example and in CST there exists a principle known commonly as the “preferential option for the poor.” Even as we understand God’s love for all people, this principle suggests we see God’s way more fully when we understand that those suffering from poverty and marginalization need distinctive aid and attention. Demonstrating love involves helping the marginalized to overcome and change oppressive situations and systems that do not enable them the opportunity to thrive either as individuals or in communities.

We see this theological principle reflected in Vincent’s mission to the rural poor. We see it in the Abrahamic traditions, most poignantly in the stories of Moses leading the Hebrew people to liberation from their oppression in Egypt. We also see it when we understand Jesus as a liberator, one who sides with the downtrodden and recognizes them at a common table. In other words, in the Vincentian and Catholic tradition, God has a distinctive love for the poor and the oppressed precisely because God’s aim is a justice that enables the flourishing of all people and all Creation. Theologian James Cone once said: “God’s liberation of the poor is the primary theme of Jesus’ gospel.”1 This is the story of who God is and always has been. It is also who we are invited to be and to imitate through our actions and Vincentian mission. Unfortunately, however, we also know that the image and theology of God as liberator can be preached but not actually put into practice.

This narrative about Vincent de Paul and the Catholic-Christian tradition serves as a lens through which to view society and our vocation. Who amongst us is being marginalized by the economic, political, and social structures that govern our society? What systems or social habits of thinking or doing exist that do not enable the flourishing of all?

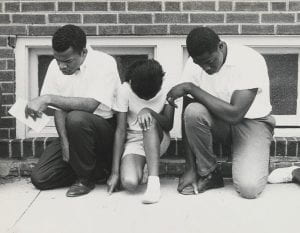

This Saturday we celebrate Juneteenth (short for June 19th) in the United States, a holiday which commemorates the emancipation of enslaved people in our country. This commemoration began in recognition of the day in 1865 when federal troops arrived in Galveston, Texas, to take control of the state and ensure the enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation.

First issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, one should note that it took more than two years after the proclamation was read for the abolition of slavery to be enforced in Texas, as well as in other Confederate-controlled areas. This example illustrates that emancipation from systems of oppression can be publicly proclaimed without being acted upon or fully realized. In fact, nearly two hundred years later, we are still seeking to bridge a gap between the freedoms from oppression promised in the proclamation and the reality faced by persons of color in our nation today.

Our Vincentian mission challenges us to continue the ongoing work of narrowing this gap between words and actions, between our ideals and reality, both individually and systemically. Vincent reminds us, “We have to preach mainly by good example.”2 If the God we proclaim is a liberator who seeks justice that enables all to flourish, this is also our charge. There is always more to do in our personal lives, in our institutions, and in our society to realize this vision. Juneteenth reminds us yet again that the work needed to fulfill the freedoms declared in the Emancipation Proclamation continues.

What might you do this summer in your own life and your work at DePaul to bridge the gap between your words or ideals and your actions, particularly related to the work of racial justice? How might you help contribute to DePaul being an institution that more fully realizes the mission, values, commitments and ideals that we proclaim?

1 James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 2011), 154.

2 Conference 134, Method to be Followed in Preaching, 20 August 1655, CCD, 11:252.

Reflection by: Mark Laboe, Associate VP, Division of Mission and Ministry