We are in a season of hope and promise here at DePaul. We recently experienced the first day of spring, a time which brings us the hope of renewed life and beauty after a sometimes-desolate winter. Students have come to the end of the quarter and are ready to enjoy spring break. We have a new basketball coach, and we are excited by the vision of a team that can unite and energize our whole community. We are in the season of Lent, a time in which Christians prepare themselves for change and refocus on what is important in preparation for Easter. We are in the month of Ramadan, where Muslims similarly embrace a period of intense spiritual practices in commemoration and gratitude for the gift of the Qur’an.

None of that means that our challenges have disappeared. Our world faces hunger, oppression, and war. Our city continues to struggle with caring for migrants and coping with violence. Individuals struggle with mental health issues, with financial challenges, with loneliness and anxiety. For those able to focus on politics, more uncertainty and anxiety can be found there. Many of us who are used to hearing and dealing with the challenges of higher education see greater challenges in our current environment than ever before. Yet, the renewal spring promises offers a chance for us to reflect.

The Muslim calendar is based on the moon. Muslims determine the start and end of Ramadan based upon its sighting. This provokes continuous debate in the community about what constitutes an accepted sighting, and the role astronomical calculations can or should play. But more importantly in this context, it has us looking to the heavens often around this time. The beauty and cycles of the moon, and many other signs of creation, can evoke feelings of wonder and mystery. In the Qur’an we are encouraged to read these signs as pointing to the Creator, while they also remind us of our kinship with others, especially those we may miss. Looking at the moon, we may think of how people on the other side of the world are seeing that same moon, or perhaps how those who have passed away used to look at that same moon as well.

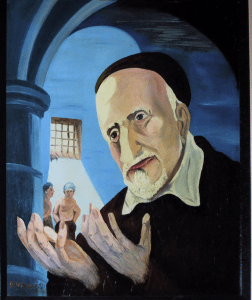

What do spiritual practices such as Ramadan and Lent invite us to during a time like this? In his Lenten message this year, Pope Francis describes the spiritual practices of Lent as comprising “a single movement of openness and self-emptying, in which we cast out the idols that weigh us down, the attachments that imprison us.”[1] While we often find comfort in prayer or other acts of worship, Saint Vincent once said that “prayer is like a mirror in which the soul sees all its stains and disfigurements.”[2] Ramadan is a time in which fasting and increased worship at night empty us of the superficial distractions that often fill our attention and the small comforts we use to cover our feelings. In such times, we first encounter ourselves as we really are—our human vulnerabilities are undeniable, the tears flow for all the pain in ourselves and our world. But we are not left there … we also envision ourselves and our communities as they could be! We find places of connection with the Divine and with each other; places of radical hospitality and generosity; and places of repentance, forgiveness, and transformation. An imaginative vision of a better future fuels our work toward change and helps us persevere through the difficulties we encounter along the way.

For Reflection:

In what season do you find yourself, personally or in your work at DePaul? What are you learning about yourself in this season? What is the vision of the future that inspires hope and energy for transformation in you?

Reflection by: Abdul-Malik Ryan, Assistant Director, Religious Diversity and Pastoral Care.

For more information on some of the diverse religious holidays being observed at DePaul this spring please visit https://blogs.depaul.edu/dmm/about/1098-2/spring-depauls-season-of-celebrating-religious-holidays/

[1] Message of the Holy Father Francis for Lent 2024, 01.02.2024, at: Through the Desert God Leads us to Freedom.

[2] Conference 37, Mental Prayer, 31 May 1648, CCD, 9:327. See: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentian_ebooks/34/.