Written By: Siobhan O’Donoghue, PhD, Director of Faculty and Staff Engagement, Division of Mission and Ministry

Some of you reading this may be familiar with the Chicago street named Ozanam Avenue, but how many know who this street is named after? Frédéric Ozanam was a French Catholic literary scholar, lawyer, professor, social advocate, and lay Catholic leader. Of all the Vincentian Family members, Ozanam has always had a special place in my heart. For me, he models something essential about how we can make our Vincentian mission concrete through our actions.

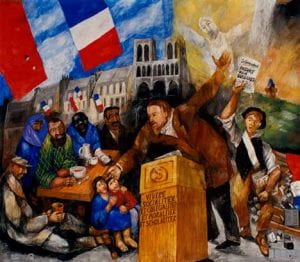

I first learned of Ozanam when I was a teenager at school in the UK. Inspired by the idea of a faith that does justice and eager to engage in community service, I had joined a school-based conference of the St. Vincent de Paul Society. Ozanam, as I soon learned, was the principal founder of the original society. He had founded the organization with a group of friends in 1833 while a university student. They named it after St. Vincent de Paul because he was considered “a national hero of social service” and admired by many in France, even those who were anti-Church. [1] The members’ goal was to help those who were poor, while at the same time developing their own faith. Keen to learn more about him, I happened upon a biography about Ozanam called Apostle in a Top Hat. Today, I might be inclined to be more discerning when choosing a biography. But at that time, the idea of interrogating a text for its authenticity was beyond me. For me, Ozanam represented a social justice icon and a man who was set on fire by a quest for faith and justice. His journey spoke deeply to my idealistic self. I devoured the book and have never forgotten the cover: a Victorian gentleman tipping an impossibly large top hat!

As I think back, our school-based St. Vincent de Paul Society was a modest entity. A motley crew of awkward, if well-meaning teenagers who, while moderately concerned about the state of the world, were primarily driven by the idea of long summer afternoons of not having to be in class. Our mission was to visit people in their homes who were seeking some kind of support, listen to them, and try to alleviate some of their needs with our adolescent vigor, then report back to the group on their well-being. We would also pray for, and sometimes with, those we visited. Our group was supported by a school chaplain, who could provide a higher level of intervention, if it was warranted.

Often, such home visits meant simply sitting with people in the humblest of homes and, in a show of true British hospitality, sharing a cup of tea, biscuits, and a listening ear, while they recounted the trials and tribulations of their days. While hardly backbreaking work or enacting any admirable social change, it was a powerful act of recognizing the dignity of another, and a way of saying, “We see you and we care.” We were grateful for the experience. We even got to feel somewhat proud of our adolescent selves, out serving in the community, no matter our real motivation for such engagement. In his time, Ozanam came to believe that face-to-face contact with poor families provided him with invaluable experiential learning, which in turn caused him to profoundly reshape his perceptions. My own experience of being a member of the St. Vincent de Paul Society also challenged my preconceived (and sometimes ill-informed) notions of poverty and social deprivation and reinforced for me the essentiality of interpersonal connection.

Today, the St. Vincent de Paul Society continues to be active in 155 countries. It has 800,000 members across 48,000 conferences, along with 1.5 million volunteers and collaborators. They serve over 30 million people worldwide every day. Conferences are based in churches, schools, community centers, hospitals, etc. [2] Their mission continues to be to offer support to people in need, particularly those living in poverty. The home visit remains an integral part of the service they provide. In this way, their ministry harkens back to the time of Ozanam when members would take firewood, food, and money to the homes of those who were poor. Yet, even in the days of the original conferences, it was never about the firewood, or the provision of goods, or funds. Rather it was about the compassionate spirit with which the members approached the visits. While certainly home visits were never the most efficient way to deliver assistance, they served as an important way to honor the dignity of the other by providing a moment of true presence and care, in a world that was often too busy to take the time to invest in such relationality. It is the spirit of love, respect, justice, hope, and joy that still defines this work, through which the members strive to shape a more just and compassionate world.

Admittedly, making home visits can be personally inconvenient and can even feel a little awkward. However, this simple act of humanity can transform a transactional service delivery into a meaningful encounter of mutuality, thus inviting a bond of intimacy, which no technological operation could ever provide. As Ozanam recognized, personal visits were a point of mutual exchange where both the visitor and the visited were beneficiaries. [3] This model of the home visit further hearkens back to the legacy of Vincent de Paul and the familiar story of the white tablecloth, a metaphor that calls us to approach all we do with the utmost care for the dignity of others. [4]

So, what wisdom might the humble home visit offer to us at DePaul today? In addressing this, I find myself recalling a question that a faculty member once posed to me after she had read DePaul’s new mission statement: “Dignity is a great concept, but how do we operationalize it?” I believe that the wisdom of the home visit can help us address this complex question, since the same personalism lies at its very heart and is modeled at DePaul each and every day. For, while the provision of concrete resources to help address a need is essential, it is the gift of sincere listening and a compassionate heart that defines us and makes all the difference.

Essentially, it is the spirit of love, respect, care, and empathy, and the commitment to right relationship that must inform how we support our students—and each other—at DePaul. Personalism must never be overshadowed by a mentality of just getting the job done in the most efficient way possible if it crowds out the personhood of those standing in front of us. Indeed, personalism must continue to define any institution that calls itself Vincentian. While efficiency and effectiveness are certainly important, personalism must continue to shape who we are and inform who we are called to be, just as it did in the time of Ozanam, and certainly in the days of Vincent and Louise before him. We come from a rich tradition, and it is up to us to live out its rich legacy.

Reflection questions:

- When was the last time you encountered personalism at DePaul?

- What might it look like for efficiency and personalism to exist seamlessly at DePaul?

Reflection by: Siobhan O’Donoghue, PhD, Director of Faculty and Staff Engagement, Division of Mission and Ministry

[1] Thomas McKenna, C.M. “Frédéric Ozanam’s Tactical Wisdom for Today’s Consumer Society,” Vincentian Heritage 30:1 (2010): 11. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol30/iss1/1.

[2] “Where Are We?” International Confederation of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, accessed January 29, 2025, https://www.ssvpglobal.org/where-we-are/.

[3] McKenna, “Frédéric Ozanam’s Tactical Wisdom,” 16.

[4] See “The Story of the White Tablecloth,” posted August 15, 2011 by Mission and Ministry DePaul University, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0CgJVAC7Na8.