Beliefs and Portfolios: New Measurement and Facts

By Stefano Giglio, Professor of Finance, Yale School of Management; Matteo Maggiori, Associate Professor of Finance, Stanford Graduate School of Business; Johannes Stroebel, Professor of Finance, New York University Stern School of Business; and Stephen P. Utkus, Visiting Scholar, Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

Beliefs about the future play a central role in determining intertemporal decisions. For example, when households decide how to invest their savings, beliefs about future stock market returns and the economy should materially influence their allocations. A better understanding of how beliefs are formed and to what extent they are reflected in actual behavior is therefore important to test and develop macro-finance theories.

One of the difficulties in studying investor beliefs is that they are generally hard to measure. In recent years, researchers in economics and finance have increasingly turned to survey data to calibrate and test macro-finance models. The unique benefit of survey data is that it can provide direct evidence on the beliefs of different agents about future economic outcomes such as returns and cash flows. While surveys have well-known downsides – including many issues related to measurement error – they open an informative window into the investors’ minds. Observing investors’ beliefs alone, however, is not enough to characterize the extent to which investors act on those beliefs. Indeed, to fully understand the transmission of investor beliefs to actions such as their trading and portfolio allocations, it is necessary to link the individual surveys to the actions of the survey respondents.

To make progress on understanding the relationship between investor beliefs and investment decisions, we have collaborated with Vanguard to administer a newly-designed online expectations survey – the GMSU-Vanguard survey – to a large panel of individual retail and pension investors with substantial wealth invested in financial markets. One unique benefit of this set-up is that we can link the surveys to anonymized administrative data on their investment holdings and trading at Vanguard, helping us explore the quantitative relationship between beliefs and behavior.

The survey elicits the investors’ beliefs about future stock returns, GDP growth, and bond returns. It asks about investors’ expectations at different horizons (e.g., 1 year and 10 years) and the perceived probabilities of different outcomes (e.g., what is the probability of a 10% or 30% drop in the stock market over the coming year). The survey was designed to be short in order to encourage investors to take it repeatedly over time. The survey sample includes U.S.-based clients of Vanguard, one of the world’s largest asset management firms. The survey, which is still ongoing, started in February 2017 and is administered every two months; in each wave, Vanguard typically receives more than 2,000 responses, many of them from repeat respondents.

We presented the initial insights from this ongoing research project in two papers. In “Five Facts About Beliefs and Portfolios” (Giglio et al., 2021, forthcoming in American Economic Review), we document five stylized facts that are informative for the design of macro-finance models. In “The Joint Dynamics of Investor Beliefs and Trading During the COVID-19 Crash” (Giglio et al., 2021) we focus specifically on the period February 2020 – April 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a large U.S. stock market crash; this focus allows us to study how beliefs and trading evolve during a market crash.

We briefly summarize below the key take-aways from these research papers.

- The Transmission of Beliefs to Portfolios

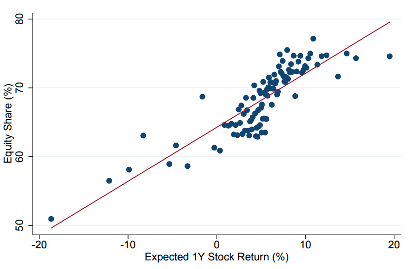

A first insight relates the equity allocation in investors’ portfolios to their beliefs about one-year expected stock returns. Figure 1 (top of page 4) shows a conditional binscatter plot with portfolio equity share on the vertical axis and expected returns on the horizontal axis.

There is a strong positive relation between expected returns as measured by survey answers and portfolios. However, the sensitivity of portfolios to expected returns is low on average across individuals. Intuitively, compare investors who expect around 0% return over the next year to investors who expect 10% return over the next year. Frictionless investment models would imply vastly different portfolios for these investors (controlling for measures of risk). Instead, we find that they hold on average portfolios with 65% and 72% in equity, respectively.

While the average sensitivity of portfolios to beliefs is lower than that in frictionless models, there is substantial heterogeneity in that sensitivity across investors. Interestingly, this sensitivity lines up with different measures of frictions investors face.

Investors who pay more attention to their accounts, investors who trade more frequently, and investors who are more confident in their beliefs all have portfolios that are more strongly aligned with their expected stock returns. Holdings in tax-advantaged accounts are more sensitive to investors’ expectations than holdings in accounts subject to capital gains taxes. Holdings in institutionally managed defined-contribution plans are about half as sensitive to changes in expectations as portfolios in individually managed plans, likely a result of the frequent use of default options in these accounts.

Importantly, when we focus on a subset of investors who might face fewer frictions, we find their portfolio allocations to align with their beliefs with a sensitivity that is substantially closer to that predicted by frictionless models.

This finding suggests that the fact that, on average, survey responses and portfolio allocations do not vary as much as predicted by frictionless models, is not due to issues with survey data. Instead, it highlights that in order for models to have reliable quantitative implications, they need to better account for the large and heterogeneous frictions across investors.

We summarize this fact as follows:

Fact 1. Portfolio shares vary systematically with individuals’ beliefs. However, the average sensitivity of an investor’s portfolio share in equity to that investor’s expected stock market returns is lower than predicted by frictionless asset pricing models. This sensitivity is higher in tax-advantaged accounts, and is increasing in wealth, investor trading frequency, investor attention, and investor confidence.

Figure 1. Figure shows a conditional binscatter plot of survey respondents’ expected 1-year stock returns and the equity share in their portfolios, conditional on the respondents’ age, gender, region, wealth, and the survey wave.

- Beliefs and Trading Behavior

We next study whether changes in beliefs during a certain time period predict whether investors trade during that period, and if so, whether it is affected by how much they trade. Fact 2 summarizes our findings from this analysis:

Fact 2. While belief changes have little to no explanatory power for predicting when trading occurs (extensive margin of trading), they explain both the direction and magnitude of trading conditional on a trade occurring (intensive margin of trading).

Our Facts 1 and 2 have interesting implications for macro-finance models. A traditional approach in behavioral finance has been to use survey answers on expected returns, which are quite volatile, as an input to models that aim to explain the excess volatility of the stock market relative to dividends. A crucial element of these models is that the variation in expectations is strongly reflected in portfolio demand because the transmissions of beliefs to portfolios is frictionless in the models. We show that this is not the case in the data. Models that want to map survey evidence on beliefs to general equilibrium asset prices need to take seriously the quantitative extent of transmissions of beliefs to portfolio demand and account for its heterogeneity. A number of recent modeling advances take exactly this route, providing a promising new avenue for the further development of behavioral finance models.

- Belief Heterogeneity

Next, we focus on investigating the belief heterogeneity in our survey. How much of the panel variation in beliefs is driven by cross-sectional heterogeneity or common time-series movements, and how much of the cross-sectional heterogeneity is persistent rather than reflecting individuals changing their beliefs?

More formally, we can use our panel of responses to perform a statistical decomposition of the variance of beliefs into three components: fixed individual characteristics, common variation in individual beliefs over time, and a residual component that captures both idiosyncratic individual time variation and measurement error.

We find that time fixed effects (capturing time variation in the average belief common across all investors) only explain around 1% of the total variation. Instead, individual fixed effects explain around 50% to 60% of the total variation in beliefs in our panel. This means that individual beliefs are mostly characterized by heterogenous and persistent individual effects: pessimists tend to remain pessimistic over time; optimists tend to remain optimistic; and the difference in their views is large. Despite the importance of the individual fixed effects, we do not find that much of the variation in individuals’ beliefs can be explained by their characteristics.

We summarize our results in Fact 3:

Fact 3. Variation in individual beliefs is mostly characterized by heterogeneous individual fixed effects: between 50% and 60% of variation across responses is due to individual fixed effects and only 1% is due to common time series variation. The remaining variation is accounted for by idiosyncratic individual variation over time and measurement error. Only a small part of the persistent heterogeneity in individual beliefs is explained by observable demographic characteristics.

This fact points to an underexplored dimension of the data, individual heterogeneity. The use of surveys has often been reduced, due to data availability, to tracking the mean across respondents over time. This is, of course, a useful moment of the data, but one that captures only a very small component of overall belief variation. Models that explicitly account for heterogeneous beliefs might find our estimates useful in disciplining their quantitative implications.

- Covariation Across Questions

We next study how correlated the answers are across different questions. We find that individuals who are more optimistic about the short-run are more optimistic about the long-run, and people who are more optimistic about the real economy are also more optimistic about the stock market. In addition to these cross-sectional results, we also find that over time, when individuals become more optimistic about the economy, they also become more optimistic about the stock market. These findings suggest that expected dividend growth (with should be related to expectations about the real economy) is an important driver of beliefs (and ultimately quantities and prices) in the stock market.

We summarize this as Fact 4:

Fact 4. Individuals who expect higher cash flows also expect higher returns.

- A Behavioral Approach to Rare Disasters

An important strand of the macro-finance literature has emphasized that expectations of rare but potentially catastrophic negative events, called rare disasters, can help explain portfolio holdings and asset prices. This literature has stressed that the expected probability and size of rare disasters are some of the most important moments for understanding risks and returns.

We find that individuals who report a higher subjective probability of stock-market rare disasters also report lower expected stock-market returns both across people and within people over time. This result is surprising in light of the existing literature, because in standard representative agent rational-expectation equilibrium models with rare disasters, expected returns and the probability of disasters are positively related. The intuition is that a higher probability of disaster induces individuals to demand a higher compensation for holding the stock market and this makes equilibrium expected returns higher (controlling for the changes in the risk-free rate).

Our results here suggest possible avenues to extend standard models to capture the investors’ perceptions of rare disasters that are revealed from the survey. For example, these results suggest that there is significant disagreement across investors about the disaster probability. Since the current stock price is observed by all agents, then those agents who think that disasters are more likely also tend to expect lower returns, thus generating the pattern we document.

We summarize these results in our last fact:

Fact 5. Higher expectations of stock market disasters are associated with lower expected stock market returns, both across and within individuals.

- The COVID-Crash

Many of the patterns we documented above were particularly strong during the COVID-crash. While beliefs on average fell quite substantially, from about 6% average 1-year expected stock returns in February 2020 to just over 1% in March 2020, more than 70% of investors didn’t actively adjust their portfolios, and even those that did only adjusted them relatively little (on average, by just a few percentage points), consistent with the low sensitivity documented in Fact 1 above. In addition, we observed relatively small expected declines in real economic activity, in particular compared to the large declines in expected stock returns. In addition to these changes in average expected returns, disagreement among investors increased substantially after the COVID-crash. These moments are useful inputs into the design of new asset pricing models over the coming years, which should aim to jointly explain both prices and quantities.

References

Giglio, S., Maggiori, M., Stroebel, J., & Utkus, S. (2021). Five facts about beliefs and portfolios.

American Economic Review, forthcoming.

Giglio, S., Maggiori, M., Stroebel, J., & Utkus, S. (2021). The joint dynamic of investor beliefs

and trading during the COVID-19 crash. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), 118(4), e2010316118, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2010316118.

About the Authors

Dr. Stefano Giglio is a Professor of Finance at the Yale School of Management. With research interests that include asset pricing, macroeconomics, and financial economics, Dr. Giglio serves as a NBER Research Associate and a CEPR Research Affiliate. His work has been published in the Journal of Political Economy, Review of Financial Studies, and the Journal of Financial Economics, among many others, as well as popular news outlets such as Forbes and the Economist. He has received several awards for his work, including the Fama-DFA Prize for the Best Paper in the Journal of Financial Economics, the Jacob Gold & Associates Best Paper Prize, and the UBS Global Asset Management Award for Research in Investments.

Dr. Stefano Giglio is a Professor of Finance at the Yale School of Management. With research interests that include asset pricing, macroeconomics, and financial economics, Dr. Giglio serves as a NBER Research Associate and a CEPR Research Affiliate. His work has been published in the Journal of Political Economy, Review of Financial Studies, and the Journal of Financial Economics, among many others, as well as popular news outlets such as Forbes and the Economist. He has received several awards for his work, including the Fama-DFA Prize for the Best Paper in the Journal of Financial Economics, the Jacob Gold & Associates Best Paper Prize, and the UBS Global Asset Management Award for Research in Investments.

Dr. Matteo Maggiori is an Associate Professor of Finance at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He is a co-founder and director of the Global Capital Allocation Project. His research focuses on international macroeconomics and finance, and his research topics have included the analysis of exchange rate dynamics, global capital flows, the international financial system, the role of the dollar as a reserve currency, tax havens, bubbles, expectations and portfolio investment, and very long-run discount rates. His research combines theory and data with the aim of improving international economic policy. He is a faculty research fellow at NBER and a research affiliate at the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). Among a number of honors, he is the recipient of the 2021 Fischer Black Prize awarded to an outstanding financial economist under the age of 40, the 2019 Guggenheim Fellowship, and the 2019 Carlo Alberto Medal to an outstanding Italian economist under the age of 40. His research has been funded by the National Science Foundation (CAREER grant).

Dr. Matteo Maggiori is an Associate Professor of Finance at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He is a co-founder and director of the Global Capital Allocation Project. His research focuses on international macroeconomics and finance, and his research topics have included the analysis of exchange rate dynamics, global capital flows, the international financial system, the role of the dollar as a reserve currency, tax havens, bubbles, expectations and portfolio investment, and very long-run discount rates. His research combines theory and data with the aim of improving international economic policy. He is a faculty research fellow at NBER and a research affiliate at the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). Among a number of honors, he is the recipient of the 2021 Fischer Black Prize awarded to an outstanding financial economist under the age of 40, the 2019 Guggenheim Fellowship, and the 2019 Carlo Alberto Medal to an outstanding Italian economist under the age of 40. His research has been funded by the National Science Foundation (CAREER grant).

Dr. Johannes Stroebel is the David S. Loeb Professor of Finance at the New York University Stern School of Business. In addition to serving as a CEPR Research Affiliate and an NBER Research Associate, Dr. Stroebel works at NYU Stern as the Research Director of Global Finance in the Center for Global Economy and Business, the Research Director of Climate Finance Research in the Volatility and Risk Institut, and the Research Director of the Household Finance Program at the Salomon Center. He is also an Associate Editor for Econometrica and The Journal of Political Economy. His research has been published in the Review of Financial Studies, Journal of International Economics, and the Annual Review of Financial Economics, among many others.

Dr. Johannes Stroebel is the David S. Loeb Professor of Finance at the New York University Stern School of Business. In addition to serving as a CEPR Research Affiliate and an NBER Research Associate, Dr. Stroebel works at NYU Stern as the Research Director of Global Finance in the Center for Global Economy and Business, the Research Director of Climate Finance Research in the Volatility and Risk Institut, and the Research Director of the Household Finance Program at the Salomon Center. He is also an Associate Editor for Econometrica and The Journal of Political Economy. His research has been published in the Review of Financial Studies, Journal of International Economics, and the Annual Review of Financial Economics, among many others.

Mr. Stephen P. Utkus is currently a visiting scholar at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and at Georgetown University’s Center for Financial Markets and Policy. Mr. Utkus’s research interests include household finance, behavioral economics, and retirement security and aging. He previously served as global head of investor research at Vanguard, where he held a variety of research and business leadership positions over a career spanning more than three decades.

Mr. Stephen P. Utkus is currently a visiting scholar at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and at Georgetown University’s Center for Financial Markets and Policy. Mr. Utkus’s research interests include household finance, behavioral economics, and retirement security and aging. He previously served as global head of investor research at Vanguard, where he held a variety of research and business leadership positions over a career spanning more than three decades.