Investor Expectations Shaped by Experience

Investor Expectations Shaped by Experience

By Stefan Nagel, University of Chicago, NBER, and CEPR

- Expectations of individual and professional investors are influenced by their own life-time experiences of asset returns and the macroeconomy

- Young investors are particularly strongly influenced by recent experiences

- Investors’ reliance on life-time experiences amplifies asset price booms and bust

Asset prices in financial markets reflect investors’ expectations about the future. How attractive investors perceive an investment in a risky asset depends, for example, on their expectations of prospective returns of the asset, their perception of risk, and their views about future inflation rates. Casual observation suggests that financial markets cycle through waves of optimism and pessimism. What gives rise to these cycles in expectations? Investors often seem to disagree about the outlook for the future. What are the origins of such disagreement?

Differences in experienced financial market returns and macroeconomic history help explain differences in investors’ expectations and portfolio choices. The dynamics of investors’ expectations over time shift according to the evolution of investors’ experiences as they observe new realizations of returns.

As an example, let’s suppose we observe two investors, A and B, who assess the attractiveness of a stock market investment in early 2009, during the low point of the financial crisis after the stock market had fallen dramatically. Investor A is 35 years old at that time, while investor B is 65. Suppose they form expectations about the prospective returns on a stock market investment based on the stock market returns they have experienced during their adult lives. How would their expectations change as the crisis unfolds? A younger person’s experience contains a shorter history of stock market returns. As a consequence, the recent stock market decline carries a greater weight, and shifts the experienced average return by more than for an older individual who looks back at a longer history of experiences. Thus, younger investors’ expectations about stock market returns should be more responsive to the stock market decline than older investors’.

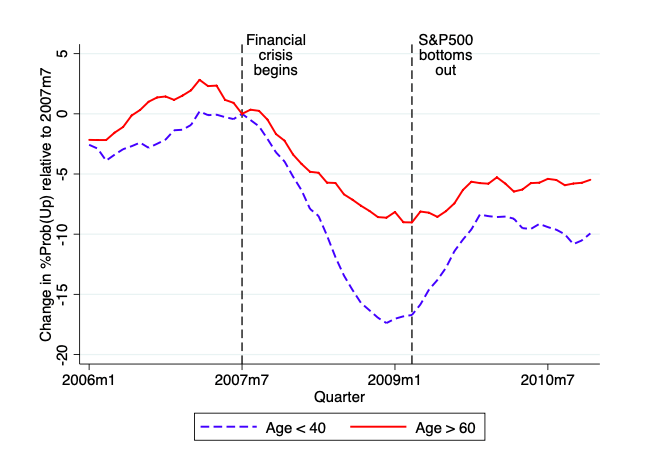

Figure 1: Beliefs about future stock market returns by age. Mean of survey respondents reported probability of a rise in the stock market over the next 12 months (Michigan Survey of Consumers) within two age groups (age < 40 and age > 60), expressed in terms of the change relative to July 2007.

Figure 1 shows that there is some truth to this conjecture. It tracks how individuals’ beliefs about the likelihood of a rise in the stock market changed with the onset of the financial crisis. As the figure shows, younger people’s beliefs had shifted substantially more (-17 percentage points) in a pessimistic direction than the older people’s beliefs (- 8 percentage points) by the time the stock market bottom was reached in early 2009. When the market recovered subsequently, the young group’s beliefs again responded more strongly, this time in the optimistic direction. The greater responsiveness of younger individuals’ beliefs to recent market declines and the subsequent recovery is exactly what one would expect when individuals form expectations based on lifetime experiences.

Malmendier and Nagel (2011) show that experience-based expectations formation helps understand individuals’ portfolio investment decisions also much more broadly in many decades prior to the financial crisis. Cohorts that have lived through periods when the stock market did poorly are more reluctant to invest in stocks and they are more pessimistic about future stock market returns than cohorts that had better stock market experiences. This explains, for example, why younger investors were unusually keen to invest in stocks following the stock market boom in the 1990s and unusually reluctant to do so following the poor stock market returns in the 1970s. Malmendier and Nagel (2016) show that experience-based expectations formation also applies to consumers’ expected inflation: individuals’ expectations of future inflation are shaped by the inflation they have experienced throughout their lives.

Experience effects of this sort are not exclusively an individual investor phenomenon. Professionals and policymakers also exhibit behavior consistent with experience effects shaping their expectations. Andanow and Rauh (2018) find that pension fund’s return expectations are influenced by their own experienced returns. Greenwood and Nagel (2009) show that young mutual fund managers were more inclined to invest in the then-booming technology stocks at the end of the late-90s than their older colleagues, but they did not earn higher returns from doing so. Chernenko, Hanson, and Sunderam (2016) find that inexperienced fund managers invested more in securitizations linked to nonprime mortgages in the years before the Great Financial Crisis, unless they had personally experienced severe or recent adverse investment outcomes earlier in their career. Malmendier, Nagel, and Yan (2018) show that differences in inflation expectations and voting behavior of members of the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee can be traced to differences in their lifetime inflation experiences.

Experience-based formation of expectations helps explain why, at a given point in time, individuals of different age can disagree about the future, as illustrated in Figure 1, but it also helps understand why the expectations of the average investor change over time. If many investors rely, to a substantial extent, on their lifetime histories of experiences to form expectations, this means that the average investors’ belief is always shaped by relatively recent financial market history. As experienced events recede into the past, memory of these events gradually fades and their influence on expectations wanes. As a consequence, a string of unusually good stock market returns—e.g., the bull market of the 1990s—generates optimism, while a string of bad news—e.g., the financial crisis around 2008—generates pessimism that eventually fades as memory of these experiences gradually loses influence on expectations.

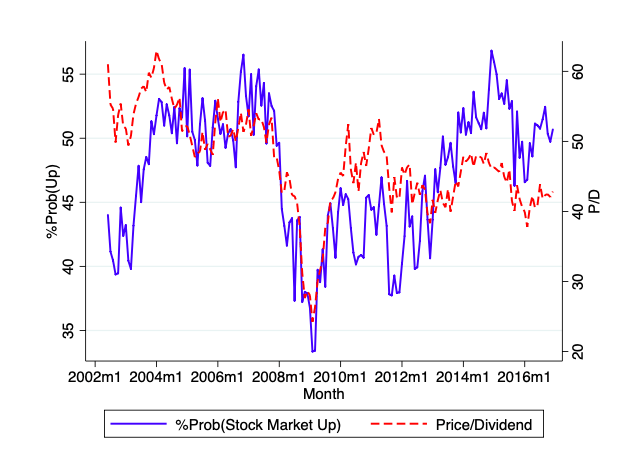

Figure 2: Beliefs about future stock market returns and stock market valuation levels. Mean of survey respondents reported probability of a rise in the stock market over the next 12 months (Michigan Survey of Consumers) and price/dividend ratio of a comprehensive stock market index (CRSP value-weighted index).

Figure 2 illustrates these cycles of investor optimism and pessimism. It is based on the same data as Figure 1, but now with the perceived probability of a rise in the stock market averaged across all survey respondents at each point in time, shown as the solid blue line. For comparison, the chart also shows the stock market’s aggregate price/dividend ratio, i.e., roughly speaking, a measure of the level of prices relative to ‘fundamentals’. The two series tend to move in the same direction. After a run up in stock prices, investors are more optimistic about future price rises in the stock market, while following a drop in stock prices, there is widespread pessimism—consistent with reliance on relatively recent stock market return experiences. Nagel and Xu (2018) show that such experience-driven cycles in investor beliefs can account for the boom-bust cycles in asset prices that are apparent in the price-dividend ratio series in Figure 2.

To conclude, experiences of macroeconomic and financial history exert a powerful influence on the expectations of individual investors and professionals. Data that are outside of the experience set of decision makers—even though they are, in principle, available in books and databases—do not appear to have the same impact on expectations. Investors find it difficult to escape the straitjacket of their own experiences. Pro-cyclical investment policies that reinforce asset price booms and bust can be the consequence.

References

Andanow, A. & Rauh, J. D. (2018.) The return expectations of institutional investors. Working Paper, Stanford University.

Chernenko, S., Hanson, S. G., & Sunderam, A. (2016.) Who neglects risk? Investor experience and the credit boom. Journal of Financial Economics, 122(2), 248-269.

Greenwood, R. & Nagel, S. (2009.) Inexperienced investors and bubbles. Journal of Financial Economics, 93(2), 239-258.

Malmendier, U. & Nagel, S. (2011.) Depression babies: Do macroeconomic experiences affect risk-taking? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(1), 373-416.

Malmendier, U. & Nagel, S. (2016.) Learning from inflation experiences. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(1), 53-87.

Malmendier, U., Nagel, S., & Yan, Z. (2018.) The making of hawks and doves. Working Paper, University of Chicago.

Nagel, S. & Xu, Z. (2018.) Asset pricing with fading memory. Working Paper, University of Chicago.

Author Bio

Dr. Stefan Nagel currently works as the Fama Family Professor of Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. He is also a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and a research fellow at the Center of Economic Policy Research (CEPR). Dr. Nagel also serves as the Executive Editor of the Journal of Finance, one of the leading academic finance journals in the world. His research interests include asset pricing, investor behavior, and risk-taking of financial intermediaries. His most recent work explores the role of personal experiences in shaping expectations about the macroeconomy and financial market returns. Before joining UChicago in 2007, Dr. Nagel taught at the University of Michigan, Stanford University, and Harvard University.

Dr. Stefan Nagel currently works as the Fama Family Professor of Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. He is also a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and a research fellow at the Center of Economic Policy Research (CEPR). Dr. Nagel also serves as the Executive Editor of the Journal of Finance, one of the leading academic finance journals in the world. His research interests include asset pricing, investor behavior, and risk-taking of financial intermediaries. His most recent work explores the role of personal experiences in shaping expectations about the macroeconomy and financial market returns. Before joining UChicago in 2007, Dr. Nagel taught at the University of Michigan, Stanford University, and Harvard University.