By C. Scott Smith, Assistant Director and Riley O’Neil

Chicago’s reputation as a “bike-friendly” city seems to grow stronger by the day, but many people still have only a vague understanding of why this reputation is so well-deserved. While some point to the city’s Bloomingdale Trail (or The 606) and Divvy bike-sharing program as successful examples, most have not experienced the breadth of innovations familiar to avid cyclists, transportation planners and engineers who are continually studying how to improve active transportation networks in the city.

The Chaddick Institute fashioned an hour-long cycle ride covering a seven-mile route through downtown Chicago that provides rich insights into the city’s remarkable evolution and transformation in bicycle infrastructure. Riding this loop illustrates why Bicycle Magazine awarded Chicago “Best Bike City” in 2016 and draws attention to major shifts in transportation planning that are reshaping how we get around. Click the numbers on the map–which also correspond to the numbers referenced in the blog–to get additional information for each point of interest.

SETTING THE SCENE

Start your tour at the Divvy bike-share station at Adams & Wabash (1) and head down Jackson Blvd toward the Lakefront Trail (2), which is properly regarded as “first generation” modern bicycle infrastructure. Dedicated in 1963, the more than a half-century old trail is akin to a bicycle highway, hugging Lake Michigan’s shoreline and buffering riders from the nearby highway congestion (3). The Navy Pier flyover bridge (4) promises to enhance movement along this famously congested trail by allowing pedestrians and cyclists uninterrupted travel over its entire 18.5-mile span.

The potential for cycling along Chicago’s waterways is evident as you head east through the Riverwalk gateway (5) along the river’s main stem. Although the newer (2016) landscaping and street furniture along this segment (6) of the Chicago River are enticing for pedestrians, the right angled turns, narrow pathways and infrequent exit/entrance ramps make for a less desirable cycling experience. Now, zig-zag up the “riverbank” toward Wacker Drive.

Back on street left, a compelling picture of contemporary urban cycling emerges in the form of the new barrier protected bike lane (or cycle track) along Randolph Street (7). Finished in 2016, the Randolph Street redesign—complete with bicycle traffic signals (8)—is the most recent among similar protected paths constructed through the heart of the city, including those on Clinton (2015), Washington (2015) and Dearborn (2011).

The culmination of Chicago’s active transportation infrastructure is asserted in the Dutch-inspired protected intersection at the corner of Washington and Franklin (9). Developed as part of Chicago’s Loop Link project (10), the intersection features mode-specific colored pavement (green for bicycle, and red for bus) as well as concrete islands and curbs that shield both pedestrians and cyclists from turning vehicles. This urban bikeway design—derived from guidelines promoted by NACTO—reduces conflicts between different transportation modes and has caught on in other cities around the country including San Francisco, Austin, and Atlanta.

As you move through this well-integrated system—including a stage turn at LaSalle and Washington (11), a colored zone in the intersection created to enhance the safety of turns for cyclists—remember that the reconfiguration of public rights-of-way to support bicycling marks a return to “mode mixing” on streets not seen since the early twentieth century, when horse-drawn carriages and streetcars were part of the mix. Again, steer west onto Randolph Street beneath the Metra viaduct (12) and head north on Clinton toward Milwaukee Ave–dubbed the “Hipster Highway”–the highest volume cycling route in the city.

(At this point you are about halfway through the tour. If you are using a Divvy bike, remember that trips over 30 minutes cost more. Consider exchanging your bike at the Clinton and Lake Divvy station. The map above shows all 28 Divvy stations within 500 feet of the seven-mile route.)

LEARNING BY SEEING

The next phase of the ride offers evidence of a dramatic shift from planning primarily for recreational riding on the city’s edge to planning for commuting and personal business downtown. For example, new cycling facilities—such as the bike or queue boxes (13) at the intersection of Kinzie, Desplaines and Milwaukee—put cyclists at the head of traffic lanes, making them more visible to motorists and allowing them to get ahead of queuing traffic. At peak travel times, you will see a continuous flow of bicycle commuters moving efficiently through Kinzie’s protected bike lane (14), providing them door to door convenience, and avoiding the hassle of waiting for buses and trains or sitting in traffic. Traffic signals on southbound Wells Street—another popular commuter route (15)–are timed so that Loop-bound bicycles traveling at an average speed of 12 mph will encounter a series of green traffic lights (the “Green Wave“) from Huron to Wacker.

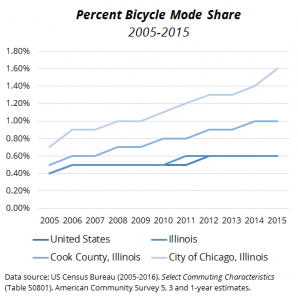

Between 1990 and 2005, the proportional share of commuter trips by bicycle in Chicago and most of the country was relatively flat. Since 2005, Chicago has experienced an impressive 129% growth in bicycle commuters, which likely underestimates the overall growth in active transportation within the city. Much of the credit for this recent upswing in cycling belongs to the city’s Streets for Cycling Plan 2020 (adopted 2011) which charted a vigorous course for bike commuting. According to David Smith, Senior Planner at the Chicago Department of Transportation, cyclists account for 20-30% of all traffic on many of the city’s most-improved bicycle corridors.

Now turn left off Randolph and head south on the Clinton Street bikeway. The protected cycle path forms critical connections to the city’s bus and commuter rail terminals including Ogilvie and Union Stations (17). Paths along both Clinton and Dearborn Street (19) allow for contra-flow cycling or travel in opposite directions. Such a design is new for Chicago and poses potential conflicts between pedestrians and cyclists, hence the on-pavement signage that cautions pedestrians to look both ways before crossing (16). Urban cycle networks are most effective when integrated with well-designed pedestrian facilities (21).

End your ride at the Federal Plaza Divvy Station on Adams Street (20). In only seven miles of downtown Chicago, you’ve now seen first-hand the benefits of investments that support urban cycling. A group of researchers from Western Michigan University’s transportation center we guided on this exact ride saw this as well. Of course, Chicago’s bicycle system can be inconsistent (e.g., buffered path along Harrison [18]) and, in several places, incomplete. But it is easy to appreciate–and see with your own eyes–how downtown Chicago has made cycling a centerpiece of many modern transportation initiatives.

Explore all of Chicago’s bike routes via CDOT’s Chicago Bike Map.